Also a recap into planners and how they can influence economic development

Wondered how your city and/or region works. Wondered what Planners do to enable (that is enable not disable) the ongoing evolution of your city and region that you live, work and play in? Does the Planner Word Salad get you absolutely lost? Don’t worry the word salad gets this planner lost too.

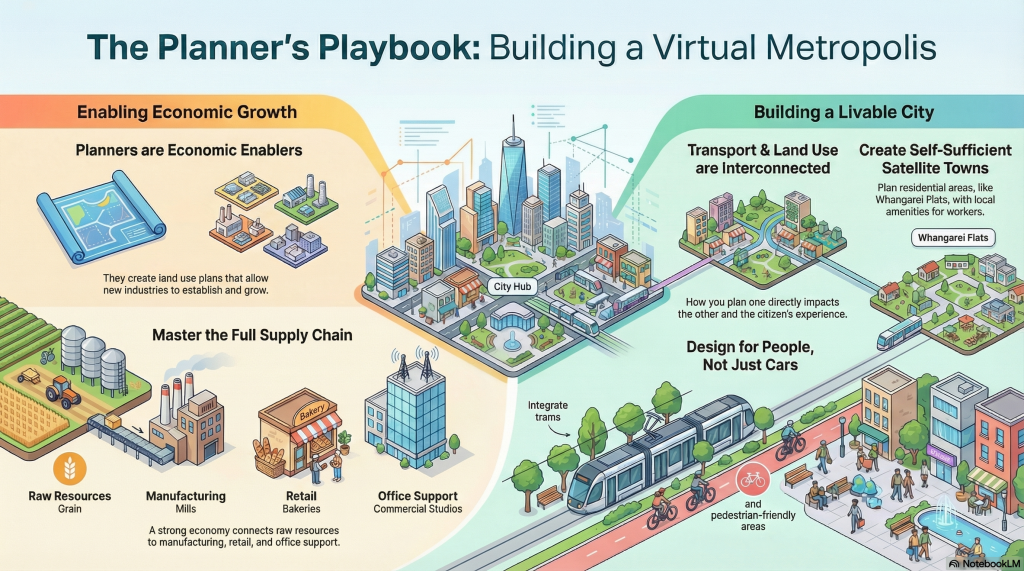

In any case I will be running a six part series using Marsden Point from Cities Skylines 2 to help decipher some of that planning word salad, what planners should be doing as economic enablers, while building a liveable city. The content will be a mix of words, infographics, slide decks, and videos. The content will be using the AI to summarise content drawn from Talking Southern Auckland, and Ben’s Cities blogs.

Part 2: A Deeper Dive. Building Safer, More Connected Communities – A Policy Framework for Integrated Cycling Networks and 30 km/h Zones

Let’s start with a slide deck on: “what happens when a real world planner uses a digital world to build the cities of tomorrow?” (Slide deck was AI generated from both my blogs)

1.0 Introduction: A Strategic Vision for Urban Mobility and Liveability

Modern municipalities face a central, defining challenge: balancing the critical need for the efficient movement of people and goods with the equally important desire to cultivate safe, liveable, and socially cohesive communities. This inherent tension often results in compromises that undermine both objectives, leading to congested transport arteries and isolated neighbourhoods.

This policy briefing makes the strategic case for an evidence-based framework designed to resolve this conflict through two core, synergistic recommendations: the development of integrated, multi-functional cycling networks and the strategic implementation of 30 km/h speed zones. This integrated approach re-envisions urban space not as a single, homogenous system, but as a diverse ecosystem requiring targeted solutions.

By doing so, this briefing provides a clear, actionable path toward creating cities that are safer, more connected, more efficient, and ultimately, more human-scaled.

2.0 The Foundational Principle: Distinguishing “Roads” from “Streets”

The cornerstone of effective transport and land-use planning is the strategic distinction between the distinct functions of a city’s thoroughfares. Not all paved surfaces serve the same purpose and failing to recognize this leads to fundamental conflicts in design and use. A clear understanding of the difference between “Roads” and “Streets” allows for the creation of a heterogeneous system that successfully balances mobility with community life.

The table below contrasts these two essential thoroughfare types:

| Thoroughfare Type | Primary Design Purpose | Associated Outcome |

| Road | To move people and goods efficiently across the city. | High-capacity, efficient transit between distinct urban areas. |

| Street | To serve people and function as an extension of living and social interaction spaces. | Places that foster community, social cohesion, and local amenity. |

When land use is mismatched with the wrong thoroughfare type, the result is inefficiency and social fragmentation. A road is hopeless in promoting social interaction and community, while streets are as hopeless in moving goods and people efficiently. This incompatibility is a primary cause of common urban problems, including isolated communities and intractable traffic congestion. This foundational concept informs a structural solution that leverages, rather than ignores, these critical differences.

3.0 A Proven Framework: The Urban Island Model

The “urban island” or “superblock” concept is a proven geographical model for organizing a city to support both efficient, large-scale movement and localized social interaction. This model organizes the urban fabric into distinct but connected modules, allowing each to thrive without compromising the other.

The core components of the urban island model are as follows:

- Perimeter Network: Major arterial roads and large-scale transit systems, such as Metro Rail and Bus Rapid Transit, form the perimeter of each urban island. This network is resolute exclusively to the efficient, city-wide movement of people and goods between islands.

- Interior Network: Inside the perimeter, a fine-grained network of streets facilitates community life. These interior networks are designed for local access, social interaction, and active transport, functioning as extensions of the homes, businesses, and public spaces they serve.

This model strategically segregates functions to achieve a dual objective: it allows people and goods to move efficiently across the municipality while preserving the safety, amenity, and social cohesion within each urban island. This structure provides the ideal template for implementing targeted, function-appropriate policies.

Building Better Cities, with economic development recap

This video summaries building better cities including a recap on the Planner’s role with economic development. Note: Video is AI generated using material from both by blogs (Talking Southern Auckland, and Ben’s Cities).

4.0 Policy Recommendation I: Strategic Speed Management for Safety and Amenity

Strategic speed management is not about slowing the entire city down. It is about applying appropriate speeds to the appropriate environments based on their designated function—ensuring safety and amenity on streets while maintaining efficiency on roads.

The core policy recommendations are as follows:

Policy Directive 1: A default speed limit of 30 km/h shall be established for all interior ‘streets’ within designated urban islands.

To ensure that city-wide mobility is not compromised, this is paired with a complementary directive for the perimeter network:

Policy Directive 2: Perimeter “roads” connecting the islands will maintain higher speed limits (e.g., 50 km/h) to ensure efficient movement is not negatively impacted.

This targeted approach debunks the myth that lower speed zones “cripple” a city. This is not a novel or risky recommendation; it is an evidence-based practice endorsed by key transport authorities. The AUSTROADs guide on speed management is clear on this matter, detailing how to effectively move people and goods efficiently on roads without sacrificing urban and metropolitan amenity. By creating more predictable traffic flow, this integrated system can even lead to an increase in average journey speeds across the city. By making interior streets safer and more people-friendly, we create the ideal environment for active transport modes like cycling.

5.0 Policy Recommendation II: An Integrated Cycling Network as Critical Urban Connector

As a matter of policy, cycling must be leveraged as a powerful transport mode that is essential for a resilient, efficient, and multi-modal urban system. Far from being a niche activity, a well-planned cycling network (encompassing both conventional bicycles and micro-mobility like e-scooters) serves as the connective tissue that “glues” various parts of the city and its transport network together, fulfilling three distinct and critical roles:

- Addressing Localized Congestion: Many urban trips are local, typically under 6 km. These short journeys are a primary source of localized congestion. Bicycles and e-scooters are a highly effective and space-efficient mode for these trips, helping to keep local traffic manageable.

- Solving the First-and-Last-Mile Gap: A successful public transport network depends on how easily people can access it. Cycling provides the critical link between a person’s home or destination and major transit spines like rail lines or busways. This solves the “first-and-last-mile” problem, reinforcing the entire public transit network and increasing its utility and reach.

- Providing a Complete Journey Option: For many commuters, cycling can serve as the primary mode of transport for their entire journey, offering a dependable, healthy, and efficient alternative to private vehicle use for a wide range of trip distances.

5.1 Essential Infrastructure Components

A successful cycling network is more than just painted lines on a road; it is a complete system that requires dedicated infrastructure.

- Cycleways: A comprehensive network must include a mix of infrastructure types to suit different environments. This includes on-road bike lanes as well as physically separated, off-road paths or “cycleways.” Separated infrastructure is particularly important along busier corridors to ensure user safety and comfort.

- End-of-Trip Facilities: A cycling network is only as strong as its weakest link, and it fails entirely without adequate end-of-trip facilities. Cyclists must have a secure place to park their bikes at their destination. This includes a full spectrum of options, from simple bike racks, sheltered bike parking, parking areas, and large shelters to secure garages and large-scale underground facilities at major transit stations, workplaces, and commercial centres.

By investing in this complete ecosystem of infrastructure, a municipality can unlock the full potential of cycling as a core component of its transport strategy.

6.0 Synergistic Benefits for the Municipality

The combined implementation of 30 km/h speed zones and integrated cycling networks should not be viewed as two separate initiatives, but as a single, powerful strategy that produces compounding positive outcomes. This framework creates a virtuous cycle: safer streets directly encourage active transport like cycling. This modal shift reduces localized vehicle congestion, which in turn enhances the reliability and speed of perimeter road networks and public transit, creating a self-reinforcing system of urban efficiency and liability.

The key synergistic benefits for the municipality include:

- Enhanced Public Safety and Community Cohesion: Lower speeds on neighbourhood streets create fundamentally safer environments that reduce the risk of serious accidents and encourage walking, social interaction, and community life.

- Efficient and Resilient Transport: An integrated system moves people effectively over long distances via roads and public transit, while active transport manages localized trips, creating a more resilient and less congested network overall.

- Strengthened Public Transit Network: By solving the first-and-last-mile problem, robust cycling infrastructure acts as a feeder system for public transit, increasing the reach, utility, and ridership of existing rail and bus services.

- Improved Urban Amenity and Liveability: Together, these policies create a city that is more pleasant, accessible, and human-scaled. The resulting improvements in safety, air quality, and noise reduction benefit residents, visitors, and businesses alike.

This integrated approach offers a comprehensive solution to many of a city’s most pressing challenges.

7.0 Conclusion and Call to Action

Adopting an integrated policy framework that combines strategic 30 km/h zones within urban islands and a robust, multi-functional cycling network is an evidence-based pathway toward a more prosperous, safe, and connected city. This approach moves beyond the false choice between vehicle efficiency and community well-being, creating a system where both can be achieved simultaneously. It is a forward-thinking investment in a city’s economic vitality, public health, and overall quality of life.

We urge municipal stakeholders, planners, and elected officials to champion and implement this transformative framework, thereby securing the economic vitality, public health, and long-term liveability of our communities.