Time to face the Truths About Our Streets

Introduction: The Invisible Architecture of Our Daily Commute

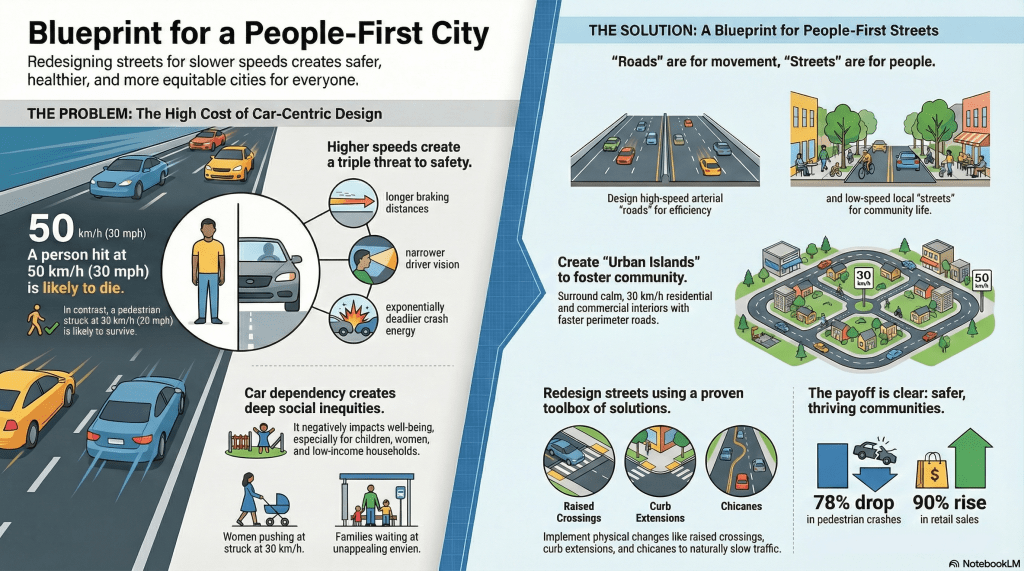

Have you ever felt a surge of anxiety stepping off a curb to cross a wide, fast-moving street, feeling exposed and small? Or perhaps you’ve experienced the slow-burning frustration of being stuck in traffic on a massive, multi-lane road that was supposedly designed for efficiency. These feelings are not just a part of modern urban life; they are the direct results of a century of design choices that have systematically prioritized the movement of cars over the safety and well-being of people.

Our streets, the most fundamental public spaces in our cities, have been shaped by an invisible architecture of assumptions that often prove to be dangerously wrong. We’ve been told that wider roads mean faster commutes and that speed limits are all it takes to keep us safe. But what if the opposite is true?

This article unpacks five surprising and counter-intuitive truths about the relationship between street design, speed, and safety. Drawing on insights from the Global Designing Cities Initiative’s “Designing for Safer Speeds” guide, we will explore how the physical shape of our streets directly impacts our health, safety, and quality of life—and how a people-centered approach can reclaim our cities for everyone.

Why are our Streets Failing?

Takeaway 1: Wider Roads Don’t Make Your Commute Faster—They Make It More Dangerous

For decades, the conventional solution to traffic congestion has been simple: add another lane or widen the existing ones. This logic, known as “forgiving design,” is borrowed from highway engineering where it helps minimize crash severity at high speeds. But in urban environments, these same features have severe and dangerous unintended consequences. The idea that expanding road capacity solves traffic is a myth that has led to cities becoming more congested and more dangerous.

The reality is that wider roads create “induced demand”—more road space simply encourages more people to drive. The new capacity is quickly filled, leading to the same frustrating congestion during peak hours. During off-peak times, however, these oversized roads provide dangerous opportunities for high-speed driving. As the “Designing for Safer Speeds” guide states, “Increasing the speed limit or expanding road capacity for private vehicles does not lead to efficient or quick transportation for people in cities.”

This insight is transformative because it challenges a core tenet of 20th-century transportation planning. The solution to traffic isn’t building more for cars; it’s about using the space we already have more intelligently by rightsizing streets to move people safely and efficiently, whether they are walking, cycling, or using transit.

Oversized travel lanes lead to higher driving speeds and fail to increase motor vehicle capacity or reduce travel times.

Takeaway 2: A Small Speed Difference Has an Exponentially Deadly Impact

When we think about the danger of a vehicle collision, it’s easy to assume the risk increases in a straight line as speed goes up. A car going twice as fast feels twice as dangerous. But the physics of a crash are far more brutal and unforgiving. The risk of death for a pedestrian does not increase linearly with vehicle speed; it increases exponentially.

The “Designing for Safer Speeds” guide highlights a critical and sobering statistic that every city planner and resident should know: “A person hit by a car at 50 km/h is eight times more likely to die than a person hit by a car at 30 km/h.” A seemingly small difference of just 20 km/h (about 12 mph) creates an eight-fold increase in the likelihood of a fatality.

This single fact provides an incredibly powerful argument for lower urban speed limits. It’s the driving principle behind policies like the “Città 30” in Bologna, Italy, which implemented a city-wide 30 km/h speed limit. The results were immediate and profound. In its first year, the policy led to a 13% reduction in all crashes, a 30% decrease in serious injuries, and a 50% drop in fatalities. The source also notes that this deadly effect might be “even more extreme in low- and medium-income countries,” where factors like vehicle type and emergency response times can further increase the risk.

Takeaway 3: The Real Speed Limit Isn’t the Sign—It’s the Street’s Design

We’ve all been on a wide, straight urban road where the posted speed limit feels unnaturally slow. These streets—often built with highway-style “forgiving design”—send a powerful, subconscious message to drivers: it is safe to go fast. These streets lack a sense of enclosure; the long sightlines, wide lanes, and smooth asphalt subconsciously communicate speed, often making the posted signs feel “inadequate” and any enforcement “arbitrary.”

The most effective way to manage speed is not through signs or enforcement alone, but by designing streets that are self-enforcing. The physical design of the street should communicate the appropriate speed to the driver intuitively. By changing the geometry of the road, we change the behavior of the driver.

This is achieved with physical design elements that force drivers to slow down to navigate them comfortably. The guide points to tools like “raised crossings, chicanes, and mini roundabouts.” Even the choice of materials can send a subconscious message; a street paved with cobblestones creates “visual friction,” feels like a place for people, and encourages slower, more careful driving in a way an asphalt road never could.

Street design should then rely on speed management tools that physically restrict speeding—such as raised crossings, chicanes, and mini roundabouts—while also seek to communicate the appropriate driving speed both explicitly through signage, and subconsciously via characteristics such as the choice of materials…

Takeaway 4: We’re Designing Our Cities for the Rarest, Biggest Vehicles

It is a “common misconception” in street design that every road must be able to comfortably accommodate the largest, least maneuverable vehicle that might ever use it—like a large fire truck or a semi-trailer. This thinking isn’t just a simple mistake; it’s a practice often reinforced by outdated laws, regulations, and even the standards used by emergency services. This leads to “overly wide roads or high-speed turns by cars,” which makes the street dangerous for its most common and most vulnerable users: people walking and cycling.

A smarter, safer approach distinguishes between a “design vehicle” and a “control vehicle.” The design vehicle is a common vehicle that uses the street routinely, like a small delivery truck or a city bus. The street’s corners and lanes can be tailored for this vehicle. The control vehicle is an occasional large vehicle, which can still use the street but may have to do so at a very low speed, perhaps even making a multi-point turn.

This distinction prevents the over-design of our streets. By refusing to sacrifice daily safety for the convenience of a rare event, cities can reclaim massive amounts of space at intersections, shorten crossing distances for pedestrians, and slow down turning cars. It represents a fundamental shift in priorities.

Safe design means tailoring elements for the most vulnerable street user rather than the largest possible vehicle.

Takeaway 5: Traffic Fatalities Are a Major Global Equity Crisis

Road traffic crashes are often framed as unavoidable “accidents.” But the data reveals a starkly different story: they are a predictable, preventable, and deeply inequitable global public health crisis. Globally, road traffic crashes are a leading cause of death for children and young adults, killing an estimated 1.19 million people every year.

The burden of this crisis is not shared equally. The “Designing for Safer Speeds” guide highlights two profound inequities:

- Economic Disparity: A staggering 92% of the world’s road fatalities occur in low- and middle-income countries, which have far fewer vehicles but much deadlier streets.

- User Vulnerability: Those with the least protection are at the greatest risk. “People walking, cycling, and riding motorcycles represent more than half of the fatal victims.”

This data reframes traffic violence as a systemic issue of social justice. For decades, street and vehicle design has prioritized the safety of those inside cars while creating lethal environments for everyone else. Treating this crisis as a public health and equity issue—rather than a collection of individual accidents—is the first step toward creating a world where no one’s life is forfeit for the sake of someone else’s convenience.

Conclusion: Reimagining Our Streets, Reclaiming Our Cities

The evidence is clear: our decades-long focus on designing streets to move cars quickly has created cities that are more dangerous, less healthy, and less equitable. The five takeaways from the Global Designing Cities Initiative reveal that a safer, more liveable urban future is not only possible, but achievable with principles that are often the opposite of what we’ve always been told. By designing for people first, we can create streets that are inherently safe.

Many of the most powerful solutions—from rightsizing streets and travel lanes and repurposing parking to building raised crosswalks—do not require inventing anything new. They simply involve reclaiming and reallocating the vast amounts of public space we have already dedicated to cars. It is about shifting our priorities from vehicle speed to human life, transforming sterile traffic corridors back into vibrant public spaces for commerce, community, and connection.

The next time you walk down your street, look at how the space is used. Who was it truly designed for, and what would it look like if it was designed for you?