Future Streets Initiative: A Phased Implementation Plan for Safer, More Liveable Public Spaces

1.0 Project Vision and Strategic Imperative

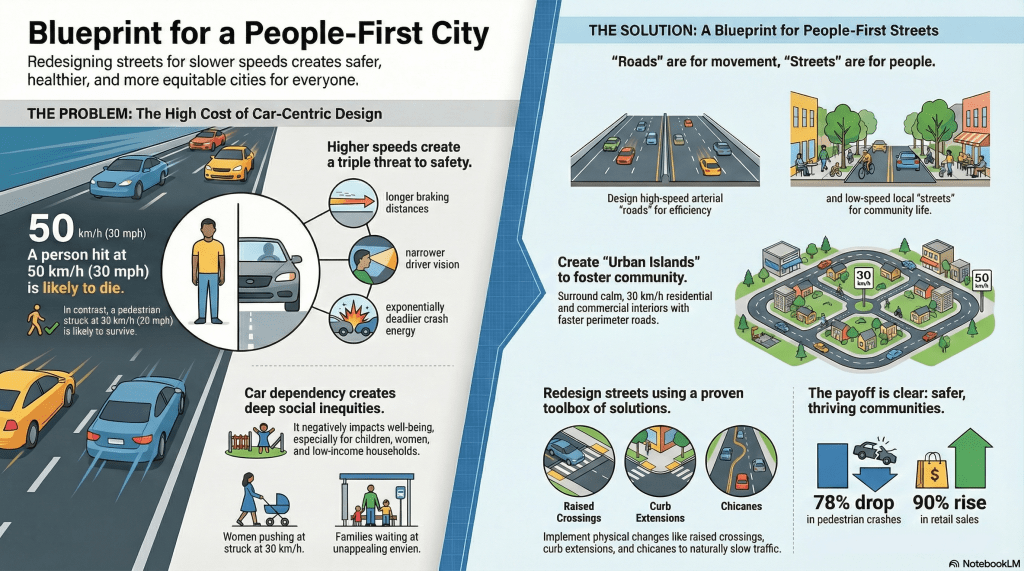

This document outlines a phased implementation plan for the Future Streets Initiative, a comprehensive program to transform our urban streetscapes. This initiative is not merely an infrastructure upgrade; it is a critical response to a global public health crisis. Globally, road traffic crashes are a leading cause of death among children and young adults, a stark reality that demands a fundamental rethinking of how we design and use our public spaces. For too long, a car-centric approach has prioritized vehicle throughput at the expense of human life and well-being. This plan, therefore, is not merely a proposal; it is a strategic mandate to reclaim our streets as safe, healthy, and equitable public spaces for everyone.

The current model of high-speed, car-centric street design has multifaceted negative consequences that extend far beyond the immediate tragedy of a crash. This project directly addresses these interconnected issues:

- Road Safety Crisis: The world sees an estimated 1.19 million people die in traffic crashes annually. Critically, “pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists represent more than half of traffic-related fatalities every year,” a clear indictment of a system that fails to protect its most vulnerable users.

- Economic Burden: The societal cost of traffic injuries and fatalities is staggering, encompassing healthcare expenditures, rehabilitation, and lost productivity. Yet investing in safety yields a powerful economic dividend: research confirms a 10% reduction in traffic deaths can raise real GDP per capita by 3.6% over 24 years.

- Public Health Detriments: Streets designed for high-speed traffic discourage physical activity, contributing to poor health outcomes like heart disease and diabetes. They also generate significant noise and air pollution, which are linked to stress, sleep disturbance, and cognitive impairment, particularly in children.

- Child Vulnerability: Children are uniquely disadvantaged by high-speed traffic. Unsafe streets limit their opportunities for independent mobility and daily physical activity, which are crucial for healthy physical, spatial, and cognitive development. These challenges are often most acute for children in lower-income communities.

The vision of the Future Streets Initiative is to move from a reactive, car-centric framework to an initiative-taking, comprehensive strategy grounded in the physical limits of human survivability. The goal is to design and build streets that are not only safer but also enhance public health, promote social equity, and improve environmental sustainability. By reallocating space and managing speeds through intelligent design, we can transform our streets from mere traffic corridors into beneficial community places that foster social interaction, support local economies, and improve the overall quality of life for all residents.

This plan establishes the clear goals and measurable objectives that will guide the execution of this transformative vision.

Reclaiming our streets

2.0 Project Goals and Objectives

Defining clear, measurable goals is of paramount strategic importance. These goals and their underlying objectives will serve as the benchmark for project success across all implementation phases, ensuring that every design choice and resource allocation aligns with our core mission. They provide the framework for evaluating outcomes and demonstrating the value of investing in human-centred street design.

The primary goals of the Future Streets Initiative are:

- Systematically Eliminate Fatalities and Serious Injuries This is the project’s foundational goal. The core principle is to design for human survivability, acknowledging that humans are fallible and that crashes will occur. By setting motor vehicle speeds at levels that are not lethal in a collision, particularly for unprotected pedestrians and cyclists, we can design a system that accommodates inevitable human error and systematically mitigates the severity of crash outcomes.

- Promote Sustainable and Active Mobility This initiative aims to create a “virtuous cycle” of mobility. By engineering streets that are safe, convenient, and comfortable for walking and cycling, we can generate a significant shift toward these sustainable modes of transport. This modal shift not only reduces greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution but also increases daily physical activity, leading to broad public health benefits.

- Enhance Community Liveability and Social Equity Street transformations are a powerful tool for community building. By calming traffic and reallocating street space previously dedicated to cars, this project will create new opportunities for social interaction, community gatherings, and children’s play. These improvements will support local businesses by increasing foot traffic and create more inviting public spaces, with a focus on ensuring these benefits are delivered equitably, particularly in lower-income areas.

- Improve Access to Key Community Destinations Safe mobility is essential for accessing the services that define a community. This goal focuses on ensuring that all people, regardless of age or physical ability, have safe and comfortable access to invaluable community assets such as schools, healthcare facilities, markets, and parks. This enhances independence and ensures that essential services are truly accessible to everyone.

These overarching goals are directly supported by the specific design principles that will inform every aspect of the project’s planning and execution.

3.0 Guiding Principles for Street Transformation

A principled approach is essential for ensuring that every component of the Future Streets Initiative is executed with consistency, quality, and unwavering alignment with the project’s vision. These principles function as the foundational philosophy for all design and implementation decisions, providing a clear and coherent framework for planners, engineers, and community partners.

The core design principles are as follows:

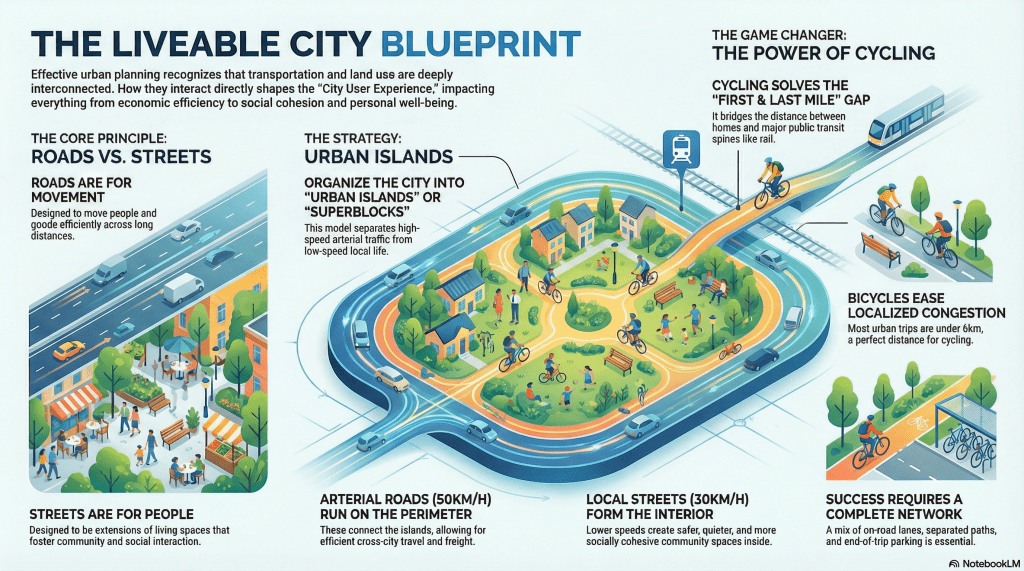

- Principle 1: Design for Safe Speeds. Street design itself must be the primary tool for managing vehicle speed. Rather than relying solely on signage or enforcement, the physical and visual cues of the street must communicate the appropriate speed to motorists. Well-designed streets make safe behaviour self-explanatory, physically discouraging speeding through measures like narrower lanes and vertical deflections. This project will adhere to target speeds of 30 km/h for school and residential zones and a maximum of 50 km/h for most other urban areas.

- Principle 2: Prioritize Vulnerable Road Users. The design process will explicitly prioritize the safety of those most at risk in a collision: pedestrians of all ages and abilities, cyclists, and motorcyclists. These users are unprotected and, in a collision, their bodies absorb the kinetic energy—often with forces far exceeding human tolerance. Therefore, the physical limits of the human body to withstand impact will be the critical design parameter for setting speeds and designing conflict points.

- Principle 3: Employ a Context-Sensitive Approach. There is no one-size-fits-all solution for street design. A single street can pass through vastly different contexts—from a dense commercial corridor to a quiet residential area—each with unique needs. Designs must be flexible and adapt to the surrounding land use, density, and community activities, ensuring that the function of the street aligns with the character of the place.

- Principle 4: Maximize Co-Benefits. Speed management tools should be selected and designed to achieve multiple objectives simultaneously. A raised crossing, for example, not only slows traffic but also provides an accessible pedestrian route. Curb extensions can be designed to incorporate green infrastructure for stormwater management, public seating to enhance the public realm, and shorter crossing distances to improve safety. Every design intervention will be evaluated for its potential to deliver co-benefits in public health, environmental sustainability, and community liveability.

These guiding principles will be applied through a structured, phased framework designed to deliver tangible results efficiently and effectively.

4.0 Phased Implementation Framework

This initiative will employ a phased implementation framework to ensure strategic, adaptable, and cost-effective delivery. This methodology allows the project to demonstrate meaningful change quickly, build community and political will, manage resources efficiently, and gather real-world performance data to refine designs before committing to large-scale, permanent capital investments.

The three-phase implementation model is detailed below:

- Phase 1: Addressing Urgent Needs (Quick-Build/Pop-Up)

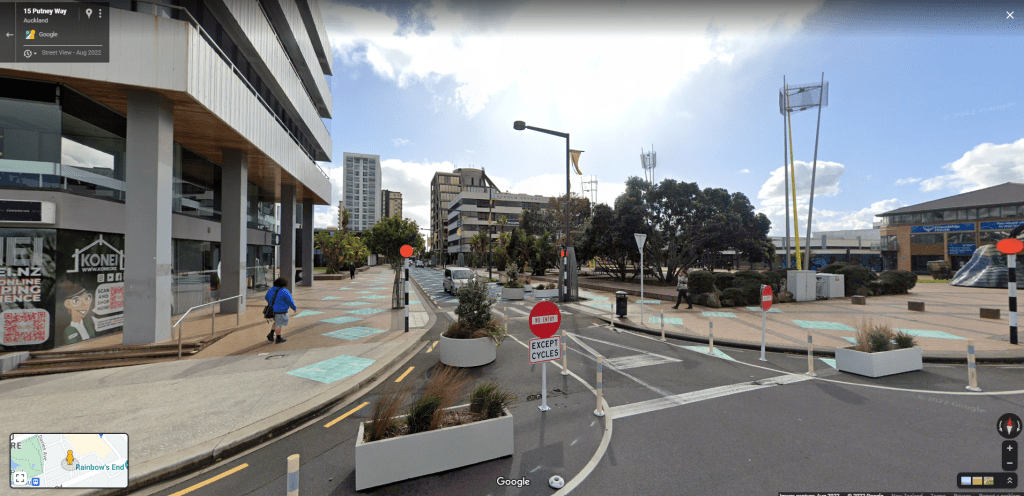

- Purpose: To quickly demonstrate the benefits of street transformations at a low cost, address critical safety issues identified through data analysis, and build tangible community support by allowing residents to experience the changes firsthand.

- Activities: Identify high-crash or high-speeding locations using available data. Define a clear timeline, scope, and funding for initial pop-up or interim solutions. Deploy these solutions to test concepts and gather immediate feedback.

- Materials: This phase utilizes low-cost, temporary, and non-permanent materials such as paint, traffic cones, moveable street furniture, and planters.

- Phase 2: Interim Interventions

- Purpose: To complement and expand upon the initial actions of Phase 1, test design concepts over a longer duration, and collect robust quantitative and qualitative data to inform and validate the final, permanent design, serving as a key component of our iterative feedback loop with the community.

- Activities: Prioritize interventions based on the results and feedback from Phase 1, as well as implementation complexity. Install semi-durable solutions that can remain in place for several months to years.

- Materials: This phase utilizes low-to-moderate cost, semi-durable materials, including fixed delineators, formal signage, and prefabricated devices such as rubber speed bumps or modular curb extensions.

- Phase 3: Full Capital Reconstruction

- Purpose: To implement the ultimate, long-term vision of the street transformation with high-quality, durable construction that requires minimal long-term maintenance.

- Activities: Execute the final, engineered design, which has been proven and refined through the iterative testing and data collection of the interim phases.

- Materials: This phase utilizes permanent, exceptionally durable materials such as concrete for curbs and crossings, pavers for aesthetic and traffic-calming effects, and permanent green infrastructure for stormwater management and placemaking.

This phased approach provides a clear pathway from initial concept to lasting change, guided by the specific strategies and design tools detailed in the following section.

5.0 Core Strategies and Design Toolbox

This section serves as a practical toolbox of proven interventions for creating safer streets. These strategies, drawn from global best practices, are designed to be combined and adapted to fit the specific context of each project location. They provide a range of physical and operational measures to achieve the project’s goals across all implementation phases.

The four primary strategic approaches for designing for safe speeds are summarized below:

| Strategy | Description and Key Actions |

| Rightsized Streets | Reallocate street space from over-dimensioned vehicle lanes to more space-efficient and sustainable modes. Key actions include narrowing or repurposing travel lanes (widths of 3m are generally sufficient and lanes under 3.5m do not decrease capacity), widening sidewalks, and adding protected cycle tracks and transit lanes. |

| Adjust Street Pace | Utilize physical and operational measures to break up long, uninterrupted road segments that encourage speeding. Key actions include installing vertical and horizontal deflection elements at intervals appropriate for the target speed (e.g., every 40-60m for a 30 km/h zone). |

| Reduce Turn Speeds | Employ physical design changes to force vehicles to slow down when turning at intersections, where conflicts are common. Key actions include tightening corner radii, removing high-speed slip lanes, and implementing protected intersections for cyclists. |

| Design Liveable Streets | Enhance the overall street environment to create a distinct sense of place, which signals to drivers that they are in a shared, low-speed environment requiring greater caution. Key actions include incorporating green infrastructure, adding public seating and art, and improving pedestrian-focused lighting. |

Specific Design Tools

Each tool is a direct application of our guiding principles: they physically design for safe speeds, inherently prioritize our most vulnerable users, can be adapted to specific contexts, and are selected to maximize co-benefits. The following tools, categorized by their primary speed reduction mechanism, will be deployed as appropriate to the site context:

- Vertical Deflection Tools: These tools create changes in the roadway’s elevation, which physically compel motorists to reduce speed for comfortable and safe passage.

- Raised Crossings/Intersections: These serve the dual benefit of physically slowing traffic while providing safe, accessible, and prioritized crossings for pedestrians at the same level as the sidewalk.

- Speed Humps/Cushions: These are effective mid-block traffic calming devices designed to reduce speeds on residential streets or on the approaches to intersections.

- Continuous Sidewalks: At intersections with minor streets, the sidewalk material and elevation are extended across the intersection, establishing clear pedestrian priority and forcing turning vehicles to slow significantly.

- Horizontal Geometry Tools: These tools alter the vehicle’s travel path, either by narrowing the roadway or creating lateral shifts that require lower speeds to navigate.

- Pinch points & Chicanes: Pinch points are curb extensions that narrow the roadway at a specific point. Chicanes create a series of alternating curb extensions that require drivers to follow a curved path, effectively slowing traffic.

- Central Islands & Medians: These visually and physically narrow the roadway, shorten pedestrian crossing distances, and provide a safe refuge for people crossing in two stages. Beyond safety, landscaped medians can incorporate green infrastructure to manage stormwater and enhance the street’s aesthetic character.

- Modal Filters: These are physical barriers (e.g., bollards, planters) or camera-enforced restrictions that prevent through-traffic on residential streets while allowing full permeability for people walking and cycling. They are instrumental in creating ‘low-traffic neighbourhoods’ that remain fully accessible to residents but are unattractive for non-local through-traffic.

Successful implementation of these physical interventions depends on a robust, parallel strategy for initiative-taking public involvement.

6.0 Community and Stakeholder Engagement

Authentic community and stakeholder engagement is a cornerstone of this initiative’s success. It is not an optional add-on but a critical component of the planning and design process. Meaningful engagement builds essential political and public support, allows the project team to learn from the invaluable local knowledge of residents, and ensures that design proposals are aligned with genuine community expectations and needs. This collaborative approach leads to better project outcomes and fosters a sense of shared ownership over our public spaces.

The key components of the engagement strategy include:

- Initial Outreach and Data Gathering: Before any design work begins, the project team will consult directly with residents, community groups, and local businesses. This process is designed to understand the “unrecorded problems” and concerns—such as near-misses, unsafe crossings, and desired community uses for street space—that do not appear in official crash data but are central to the lived experience of the neighbourhood.

- Demonstrate Possibilities: The project will use short-term, interim projects (as outlined in Phase 1) as a primary engagement tool. These quick-build demonstrations allow the community to see, feel, and experience the benefits of the proposed changes firsthand. This tangible experience is far more powerful than abstract plans and helps build a sturdy base of support for permanent investment.

- Iterative Feedback Loops: Feedback gathered during the pop-up and interim phases will be systematically collected and analysed. This information will be used to refine and improve the design before committing public funds to permanent, capital construction. This iterative process ensures the final design is responsive to community input and is optimized for local conditions.

- Engaging Vulnerable Populations: The project will make a concerted effort to engage with populations who are most vulnerable to traffic danger and who have the most to gain from safer streets. This includes targeted outreach to caregivers, children, older adults, and individuals with disabilities to ensure that the final designs meet their unique safety and accessibility needs.

This locally focused engagement strategy is powerfully reinforced by a wealth of evidence from cities around the world that have successfully implemented similar transformations.

7.0 International Precedents for Success

The Future Streets Initiative is not a theoretical exercise; it is grounded in proven strategies that have been implemented successfully in cities worldwide. The following case studies provide compelling evidence of the transformative safety, mobility, and liveability impacts that result from a principled approach to designing for safe speeds. These international precedents offer valuable lessons and a solid foundation of evidence for this project.

| City, Country | Key Interventions | Reported Impact | Relevance to this Project |

| Grenoble, France | Implemented 30 km/h speed limits on 80% of streets. | 50% reduction in pedestrian fatal/injury crashes; 9% decrease in light vehicle traffic. | Demonstrates the network-wide safety benefits of a default low-speed zone. |

| Bologna, Italy | Became the first major Italian city to implement a default 30 km/h speed limit (“Città 30”). | A 13% reduction in all crashes, a 50% reduction in fatalities, and a 30% reduction in serious injuries in the first year. | Provides a powerful precedent for a city-wide policy shift resulting in dramatic safety improvements. |

| Toronto, Canada | The King Street Pilot Project prioritized transit by restricting private vehicle through-traffic. | 16% increase in streetcar ridership; increased pedestrian activity benefiting local businesses. | Illustrates the economic and mobility co-benefits of reallocating street space away from private cars. |

| Barcelona, Spain | Implemented the “Superblocks” model, reordering the street grid to divert through-traffic. | Drastically reduced congestion, emissions, and risk to vulnerable users inside the blocks; created new pedestrian plazas. | Displays an innovative network-level strategy for creating low-traffic neighbourhoods and reclaiming public space. |

By building on this global evidence and adhering to the structured, community-focused framework detailed herein, the Future Streets Initiative will deliver a safe, vibrant, and prosperous future for our city’s public realm.