How we can move Aotearoa from it car-centric past to a people-centric future

As submissions for the Planning Bill are currently open, while the drafting of the Standardised Zones is to get underway in February, ready to go live 2027, we need to look at what we are capable of rather than romanticising a failed Past.

Using the Notebook LM AI, I summarised into a slide deck twelve of my posts from 2025 outlining that a better Aotearoa is not just possible, but it is actually waiting to be built!

A Better Aotearoa is Not Just Possible, It’s Waiting to be Built.

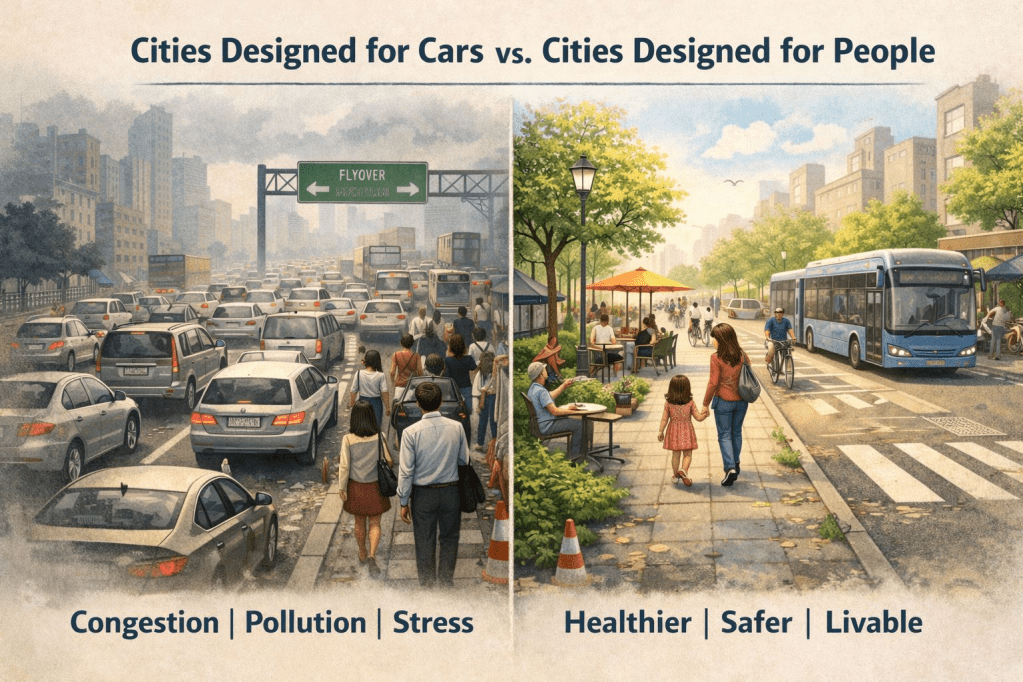

Effectively the vision is to go from congestion, pollution and stress, to healthier, safer and actually liveable.

Deeper Dive into healthier, safer, liveable cities

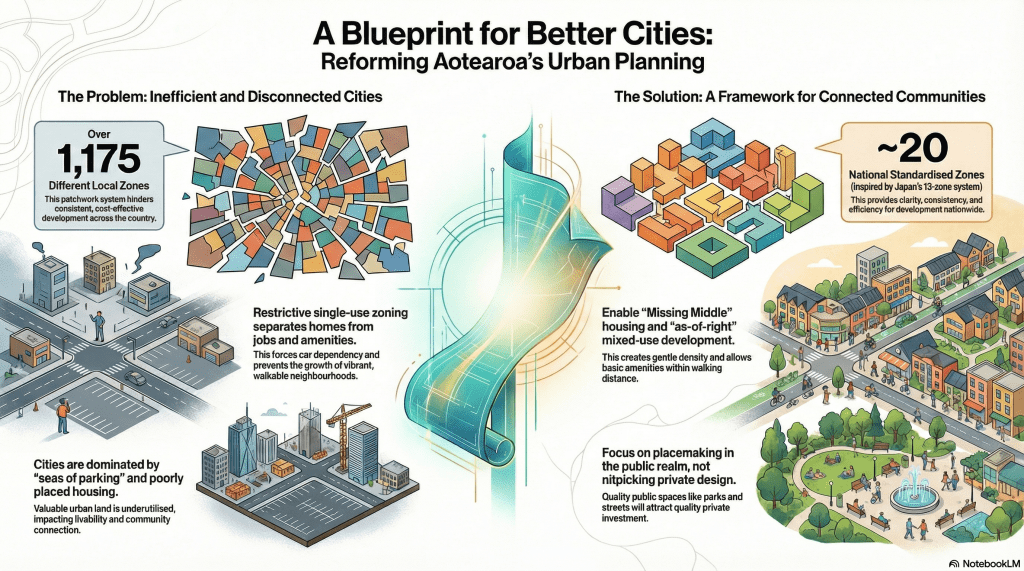

Continuing to use the AI, I pulled from my blog posts a dual-five step plan on how we can plan to build those people-first cities in Aotearoa! The first is emulating Japan in building a national planning framework. The second is when you come down to regional, sub regional, community, and even site-specific level!

Discuss what these sources say about Aotearoa Planning Reforms, in the larger context of Planning and Land-use in Japan and Aotearoa.

The planning reforms in Aotearoa (New Zealand) represent a significant shift from the decades-old Resource Management Act (RMA) toward a more streamlined Planning Act, heavily inspired by the efficiency and structure of the Japanese land-use system. This transition aims to move away from “auto-centric planning” and toward more humane, productive urban environments.

This (AI generated) podcast goes into a deep dive about the reforms, and recoding our cities (as an outcome of the reforms

The following sections discuss the reforms in the context of both Japanese and Aotearoa planning:

1. The Influence of Japanese Standardized Zoning

Aotearoa is moving toward National Standardised Zones (NSZs) to replace the current fragmented system.

- Drastic Simplification: New Zealand currently has approximately 1,175 different types of zones across various councils. By contrast, Japan uses only 12 to 13 base zones. The proposed Aotearoa reforms aim to shrink these thousands of zones down to roughly 17 to 20 standardized options.

- Consistency: Under NSZs, a “Metropolitan Centre Zone” would be functionally the same in Auckland as it is in Christchurch or Dunedin, providing the construction industry with a predictable framework that drives efficiency and lowers costs.

- The Private vs. Public Realm: The Japanese model emphasizes that planners should provide a basic framework for the private realm (via standardized zones) and focus their “magic” on placemaking in the public realm. This is intended to stop “design nitpicking” by councils, where arbitrary opinions on features like the direction of front doors can stall development.

2. Mixed Use “As-of-Right”

A central pillar of the Aotearoa reforms is enabling mixed-use development without the need for complex resource consents.

- Learning from Japan: In the Japanese system, very few zones are exclusively single-use; most allow for a blend of residential and commercial activities.

- Narrow vs. Wide Range: While major centers in Aotearoa already allow a wide range of mixed uses, the reform advocates for a “narrow range” of mixed-use activities (like cafes, dairies, or community spaces) to be permitted “as-of-right” on corner sites within residential areas. This promotes social cohesion and ensures basic amenities are within walking distance.

3. Intensification and Transit-Oriented Development (TOD)

The reforms prioritize intensification along transit corridors to maximize infrastructure utility.

- Walkable Catchments: The proposal includes standardized intensification zones of at least six storeys within walkable catchments of “rapid transit stops” (like rail or busways) and “Category 1” corridors.

- Catchment Sizes: Two options are being considered for these catchments, ranging from 400 to 1,500 meters depending on the significance of the transit hub or city center.

- Buffer Zones: Planners suggest that large arterial roads should be used for commercial or light industrial buffers rather than housing, due to pollution and noise concerns.

4. Adapting to the Aotearoa Context (Rural and Indigenous)

While Japan serves as a model, Aotearoa requires specific adaptations for its unique economy and culture:

- Rural Distinctness: Unlike urbanized Japan, Aotearoa maintains a strong agricultural and extractive economy. Consequently, the NSZs must include specific Rural Production, Rural Mixed, and Extractive zones.

- Indigenous Worldview: The reforms seek to reconcile standardized zones with the Māori worldview. This is achieved through Special Purpose Zones, such as the Hopuhopu zone, which allows iwi to develop tribal hubs (residential, educational, and business) that follow tikanga Māori.

- Papakāinga: New National Environmental Standards for Papakāinga (NES-P) are being integrated into the Planning Act to ensure Māori can develop communal settlements on ancestral land, which traditional rural zoning often restricted.

5. Managing the Urban Fringe

Aotearoa is emulating Japan’s method of controlling sprawl through Urbanization Promoting Areas (UPA) and Urbanisation Control Areas (UCA).

- In Japan, land in the UPA is prioritized for public facilities like sewage and streets to be urbanized within 10 years.

- Aotearoa’s Future Urban Zones would function similarly, signaling where urban development and infrastructure projects will be concentrated to prevent speculative investment and erratic sprawl.

The move toward standardized zoning is essentially like switching from a custom-carved puzzle to a set of standardized building blocks. While the blocks are uniform to ensure they fit together efficiently and predictably, the way they are arranged on the ground allows for a diverse and organic “messy” urban form that meets local needs without unnecessary bureaucratic friction.

What role does mixed-use zoning play in creating walkable and connected urban communities?

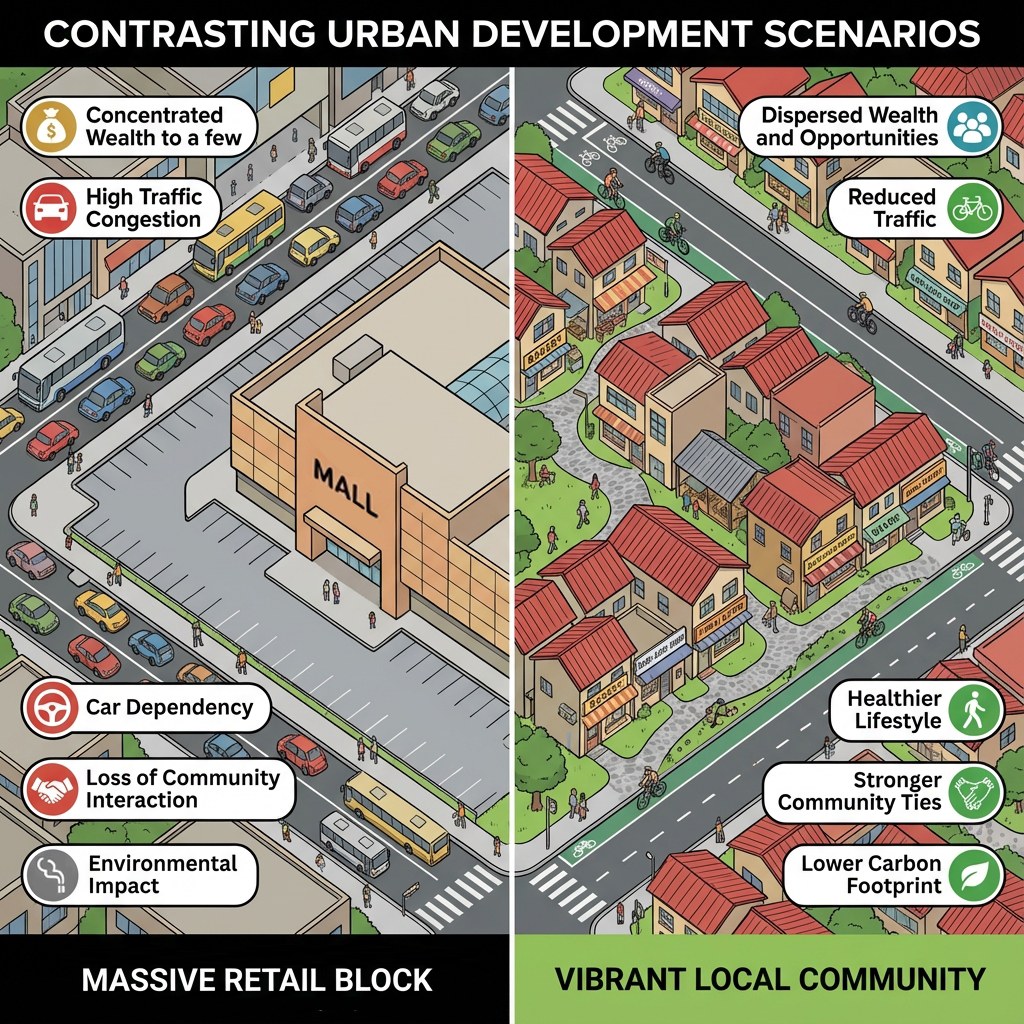

Mixed-use zoning is a foundational tool for transforming urban areas from auto-centric environments into connected, walkable communities where homes, shops, and services are layered together. According to the sources, its primary role is to ensure that “everyday life happens just outside your door” by placing essential amenities within walking distance, thereby providing viable non-car alternatives for work, school, and recreation.

The following sections detail the specific roles mixed-use zoning plays in urban development:

1. Enabling Accessibility and Walkability

By locating residential, commercial, and community activities in close proximity, mixed-use zoning makes it easier for residents to access opportunities via walking or other active travel modes. This approach creates a “human-scaled urban fabric” where small, permeable street grids allow for easy movement without a car. The sources suggest that even in traditional residential areas, allowing a “narrow range” of mixed-use activities (such as dairies, cafes, or community spaces) “as-of-right” on corner sites ensures universal access for all mobility types and promotes social cohesion.

2. Supporting Transit-Oriented Development (TOD)

Mixed-use zoning is integral to intensification along transit corridors.

- Catchment Areas: Proposed reforms suggest applying standardized zones that enable building heights of three to six storeys within specific walkable catchments (e.g., 400 to 1,200 meters) of transit stops.

- Public-Private Fusion: TODs serve as a “litmus test” where high-quality public realm placemaking influences private investment, encouraging developers to maximize the utility of land near rail and busway stations.

3. Promoting Economic and Social Vitality

Beyond physical layout, mixed-use environments foster productivity and social health:

- Economic Competition: Blending uses promotes competition and innovation by allowing businesses to respond naturally to the needs of their local communities.

- Social Cohesion: It creates spaces where people want to gather and enjoy, reducing the “loneliness” often associated with low-density, single-use sprawl.

- The “Missing Middle”: This zoning supports “gentle density” that meets the needs of a diverse demographic—including families, singles, and the elderly—while promoting “green utility”.

4. Standardizing the Urban Framework

The sources highlight the Japanese planning system as a model for mixed-use efficiency. In Japan, very few of the 13 base zones are exclusive to a single use; most allow for a mix of residential and inclusive commercial activities. Aotearoa (New Zealand) is currently looking to emulate this through National Standardised Zones (NSZs), which aim to reduce complexity and “design nitpicking” by providing a clear framework for what can be developed as-of-right. This consistency allows for a heterogeneous spatial form where development is flexible but follows a basic, predictable framework.

5. Reclaiming Underutilized Space

Mixed-use development is a key strategy for reclaiming “oceans of surface parking” in metropolitan centers. By replacing parking lots with perimeter mixed-use blocks, cities can transform dead space into thriving communities that better support stormwater management, reduce heat island effects, and improve overall livability.

In essence, mixed-use zoning acts like the connective tissue of a city, binding separate activities into a single, functional organism where the “lost art” of community building is restored through proximity and shared spaces.

So, is a better Aotearoa possible? It most certainly is when we understand the Key Fundamentals in Aotearoa Planning Reform through the Standardised Zones and Urban Transformation!