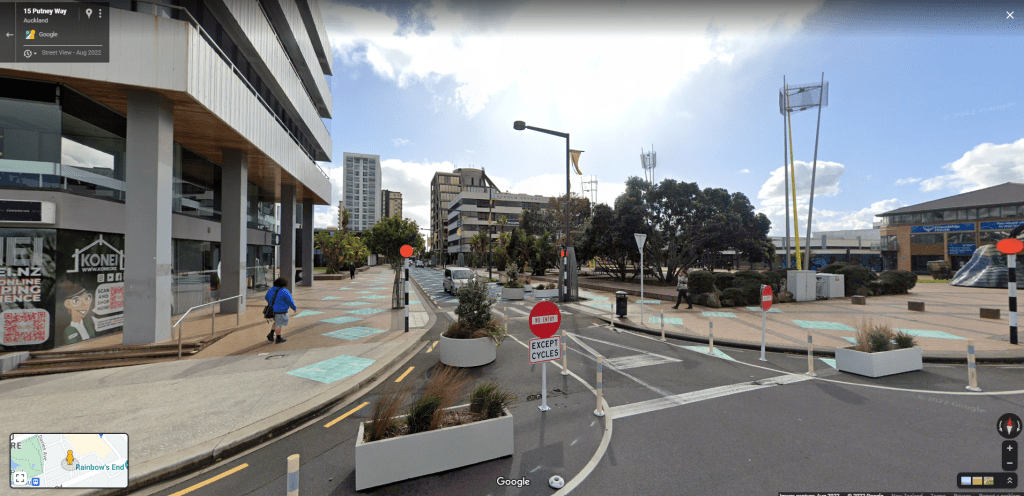

A police person’s comments in 2015 are still unacceptable in 2026!

As I was putting the rest of the Part 8.x of the Ben goes Planning Series, the AI generator (which I am using to collate and summarise my blog posts, and VOAK folder where both I have my planning stuff since 2010) highlights a post from 2015 about people first cities (or lack there of more to the point). I had a read, remembered it very well, and remembered it not only because of that police person’s comment in 2015 putting cars as primacy on our road corridors at the expense of everyone else, but 11 years later in 2026 they still do despite advances made.

The post the AI caught in its collation was this: A City That Is Equitable to All our Citizens. The text in question was:

Robin Kearns: Child-friendly city would let us ease up on cotton wool

5:00 AM Tuesday Feb 17, 2015

Last week a driver – a parent herself – sadly missed seeing three children step out to cross the road. Their subsequent injuries were unquestionably tragic. I feel for them, their families and the driver.

But an additional sadness is revealed by the comment by one of the police officers responding to the crash. They said it was “unacceptable” for young children to be walking to school without adult supervision.

My question is: unacceptable to whom? Was this a personal opinion or that of the police? Regardless, this view adds to an informal policing of parents at large; an urging to chaperone children at all times.

But whose city is this? Does Auckland belong only to adults and motorists? Perhaps we all need to slow down and reconsider our priorities.

……

Those People-First Cities

A “debate” between an expert and the host goes on about how treating driving as a right rather than a privilege has had consequences on our cities and its people. The debate (which is AI generated using the blog as source material) goes on about how we can move from a car-first to a people-first city.

The AI debate mentions renal centres, type two diabetes and the links to inactivity. This is also mentioned in the video presentation further on.

A Brave New World: Designing The People First City

Time for academic text and an infographic on how we are seeing our cities the wrong way

5 Counter-Intuitive Truths That Will Change How You See Your City

Introduction: The Street Outside Your Window

Look out your window at the street below. Chances are you see a landscape dominated by the movement, noise, and infrastructure of cars. Have you ever wondered why our cities are built this way? Why the default setting often seems hostile to pedestrians, cyclists, and community life? A different vision exists—one that puts people first.

This disconnect was starkly captured in a comment made by a police officer after a tragic crash involving three children. He said it was “unacceptable” for young children to be walking to school without adult supervision. This statement, meant to ensure safety, unintentionally reveals a profound assumption about our public spaces. As Professor Robin Kearns of the University of Auckland later asked, “unacceptable to whom?” The question cuts to the core of the issue: for whom are our cities really? If a street is inherently too dangerous for a child, have we designed it for the community, or simply for traffic?

This article explores five surprising and impactful ideas from urban planners, academics, and even video game designers that challenge our everyday assumptions about the world we build. These truths reveal that the way our cities are designed is not an accident; it is a choice—and we can choose differently.

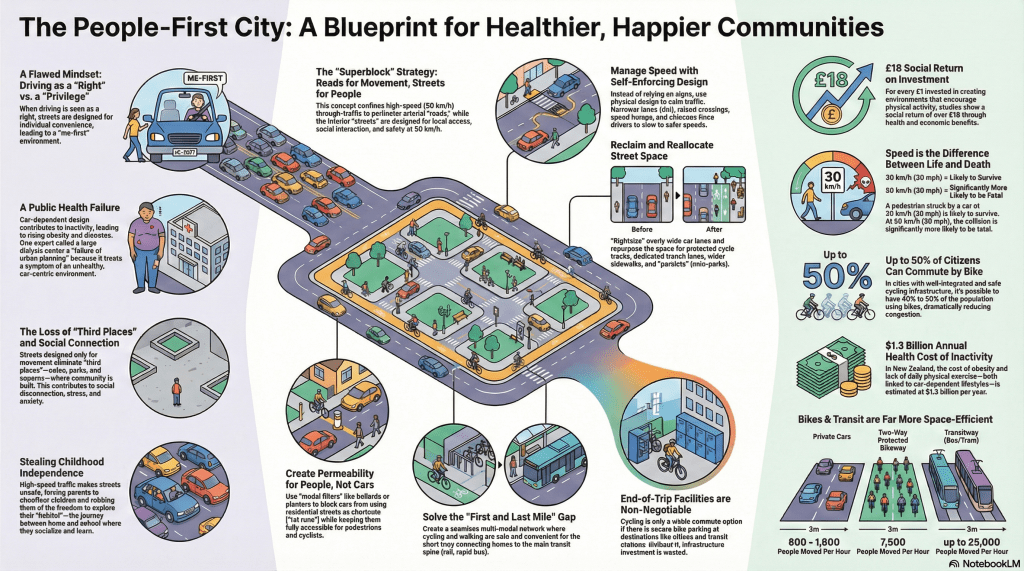

1. The Mindset Shift: Driving is a Privilege, not a Right

The most fundamental change required to rethink our cities is not about concrete or steel; it is about perspective. It is the difference between viewing driving as a “right” versus a “privilege.”

The “right” mindset is a “ME and damn everyone else” approach. It presumes the street’s primary purpose is to move private cars from one point to another as quickly as possible. Every other use—walking, cycling, playing, socializing—is secondary and must yield to the flow of traffic.

The “privilege” mindset, however, treats the road as a shared public space. It recognizes that you are piloting two tons of steel through a community’s living room. From this perspective, drivers have a responsibility to consider pedestrians, cyclists, and the well-being of the community they are passing through.

This simple mental shift is the most crucial first step. It redefines the street from a car corridor into a public space for everyone, changing the entire conversation from “how do we move more cars?” to “how do we create a better place for people?” This “me-first” mindset does not just create frustrating traffic; it has profound, and often invisible, consequences for our collective health, which brings us to a startling paradox…

2. The Health Paradox: Why a New Hospital Can Be a “Failure of Urban Planning”.

Here is a statement that sounds completely backward. As public health physician Dr. Alex Macmillan argued in a lecture at the University of Auckland, a new multi-million-dollar dialysis centre in Māngere can be seen as a “failure of urban planning.” How could a facility providing life-saving care be considered a failure?

The answer lies in treating the root cause, not just the symptom. The dialysis centre primarily treats patients with end-stage kidney disease resulting from diabetes. While the medical care is essential, its necessity points to a much larger, systemic problem.

The argument is that decades of car-dependent urban design have engineered everyday physical activity out of our lives. When walking and cycling are inconvenient or dangerous, and every trip requires a car, we become more sedentary. This contributes directly to public health crises like obesity and diabetes, which disproportionately affect lower-income communities and communities of colour. This paradox reveals the deep, often invisible link between urban design, public health, and social equity. We are building the diseases we then spend billions of dollars to treat.

Source: https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2016/6/29/the-next-baby-boom-affordable-urban-lifestyles-for-millennials-with-children

3. The Child’s Perspective: A Street Is not a Commute, it is a “Habitat”.

Professor Robin Kearns once posed a simple but profound question that cuts to the heart of our urban priorities: “But whose city is this? Does Auckland belong only to adults and motorists?”

For an adult, the journey to school is often a logistical task—a commute from point A to point B. But for a child, that same journey is a rich, complex experience. It is an environment for learning, for exploring, for building friendships, and for developing independence. In his research, Professor Kearns shared a quote from a child that perfectly captures this lost world:

I like walking to school because it is our habitat.

This single word—”habitat”—is incredibly powerful. It reframes the street from a simple path into a world of its own. When we design streets where traffic danger forces parents to chauffeur their children everywhere, we rob them of more than just a walk. We take away their independence, their opportunity for physical activity, and a crucial piece of their habitat.

4. The Accidental Experiment: Video Gamers Are Proving People-First Cities Just Work Better

What if millions of people, without any formal training in urban planning, were all part of a massive, unintentional experiment? That is exactly what is happening every day in the video game Cities: Skylines. When given a blank canvas, players consistently discover a universal truth through trial and error.

Players who attempt to solve urban problems with more highways, wider roads, and car-centric design consistently run into the same issues: crippling gridlock, rampant pollution, and eventual bankruptcy. Their virtual cities fail.

In contrast, the players who find success are the ones who intuitively rediscover the principles of good urbanism. They build dense, walkable neighbourhoods with a mix of homes and shops. Their virtual cities flourish with waterfronts full of pedestrians, dedicated tramways running down green medians, and cyclists flowing along protected lanes—scenes of vibrant public life that stand in stark contrast to the sprawling, gridlocked highways of their failed experiments. This accidental experiment shows that the principles of people-first design are not just an ideology; they are the underlying mechanics of what makes a city function well.

5. The Design Secret: Great Streets Police Themselves

A traditional car-centric street is like a high-pressure water pipe, designed only to move maximum volume as fast as possible. A people-first street is like a meandering river ecosystem. It still allows for flow, but its gentle curves, eddies, and vegetated banks naturally regulate the speed and support a rich diversity of life along its edges.

This is the core idea behind “self-enforcing streets”—roads that use physical and visual cues to make it feel unnatural and uncomfortable to drive fast. Instead of just asking for better behaviour, this approach designs for it. This is achieved through a toolkit of proven design interventions:

- Narrower travel lanes that increase a driver’s focus and attentiveness.

- Gentle curves and shifts in the road (sometimes called chicanes) that break up long, straight speedways and require drivers to pay more attention.

- Creating a “sense of enclosure” by lining the street with trees, benches, and lighting, which subconsciously tells a driver’s brain “you are in a shared, human space—slow down.”

Conclusion: The Spaces We Build, Build Us

The way we design our cities is not merely a technical exercise in managing traffic and concrete. It is a profound expression of our values. Whether it’s the simple mindset shift from a right to a privilege, the child’s view of a street as their “habitat,” or even the accidental proof found in a video game, the evidence is clear: the choices we make in design have consequences that ripple through our health, our communities, and our very identity.

If there is one lesson to take from these counter-intuitive truths, it is this: The spaces we build end up building us. The environment we create shapes who we are.

What kind of world do you want to build?

The People’s City. Are We Designing Cities for People or for Cars?

Some proposals

Proposal for a People-First Urban Design Framework: Building a More Liveable, Equitable, and Prosperous City

1.0 Introduction: The Case for a Paradigm Shift in Urban Planning

For decades, urban planning has been dominated by a car-centric model that treats our streets as infrastructure for moving vehicles. This legacy system, however, has come with significant and accumulating costs to public health, social equity, and economic vitality. This proposal advocates for a strategic and fundamental shift toward a ‘people-first’ urban design framework—one that reclaims our streets as shared public spaces and prioritizes human well-being.

The central argument of this proposal is that prioritizing active mobility, engineering for safe vehicle speeds, and creating an integrated multi-modal transit network is not merely an alternative approach, but an essential evolution for building resilient and thriving 21st-century cities. More than that, it is a critical strategy for enhancing our economic competitiveness, attracting, and retaining talent, and future-proofing our city against climate and economic shocks. This requires a philosophical shift in how we view our public rights-of-way, reframing driving not as an inherent right to convenience at any cost, but as a privilege that must coexist within a shared and equitable environment.

This document details the urgent rationale for this change by examining the consequences of our current model. It then presents a comprehensive, evidence-based design framework built on three core principles. Finally, it offers a practical and phased pathway for implementing these transformative strategies across our city.

2.0 The Consequences of Car-Centric Design: A Failure of Urban Planning

To build a more effective urban model, we must first critically evaluate the paradigm we have inherited. The intentional and unintentional consequences of designing cities around the private automobile are profound and far-reaching. Understanding these inherent flaws is the first step toward building a system that generates health and prosperity rather than eroding them.

2.1 A Public Health Crisis by Design

Our car-dependent environments are a direct contributor to negative health outcomes by discouraging routine physical activity. As one public health expert starkly noted, a major dialysis centre built primarily to treat diabetes can be seen as a “failure of urban planning.” It is a symptom of a city designed in a way that makes it difficult to walk, cycle, and be active, leading to preventable health crises that disproportionately impact vulnerable communities.

2.2 Systemic Social and Equity Injustices

The prioritization of vehicle movement has created deep injustices that are woven into the physical fabric of our city. This system actively disadvantages the most vulnerable members of our community.

- Erosion of Child Independence: High traffic speeds and dangerous streets have turned the journey to school from a “habitat” for learning and socialization into a hazardous commute. This forces parental chauffeuring, which robs children of vital environmental learning, reduces physical activity, and curtails their independence.

- Forced Car Dependence: Our land-use policies often push low-income households further away from jobs and essential services, then punish them with an inadequate public transport system. This forces them to bear the disproportionately high financial burden of vehicle ownership to participate in society.

- Social Disconnection: A landscape dominated by traffic and parking diminishes our “third places”—the parks, cafes, public squares, and libraries that serve as the living rooms of our society. These are the spaces where community connections are built, and their decline contributes to social isolation and stress.

2.3 An Economically Inefficient Model

The assumption that prioritizing vehicle throughput leads to economic prosperity is a fallacy. This is so fundamentally true that it is replicated in urban simulation games like Cities: Skylines. Players who over-invest in highways and roads invariably discover that this strategy leads to gridlock, pollution, and bankruptcy. In contrast, those who invest in walkable neighbourhoods, parks, and great public transit create vibrant, healthy, and profitable cities.

The evidence is clear: our current model is failing our residents’ health, equity, and economic well-being. This necessitates a move away from incremental fixes and toward the comprehensive solution outlined below.

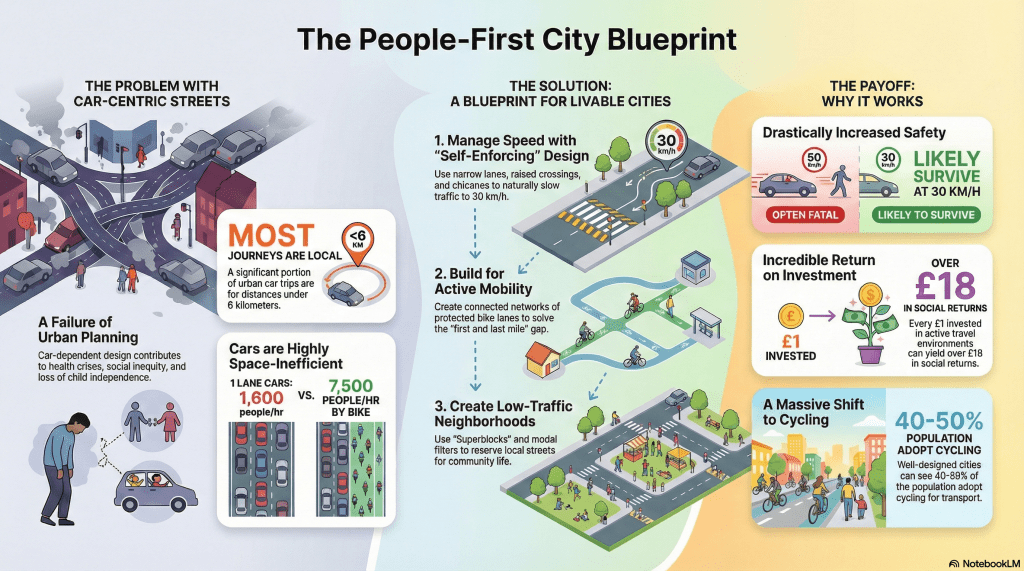

3.0 The People-First Framework: Core Principles for a Thriving City

The ‘People-First’ framework is not an abstract ideal but a practical and evidence-based blueprint for redesigning our public spaces to generate positive outcomes. It requires us to abandon the analogy of the car-centric street as a “high-pressure water pipe”—designed only to move maximum volume as fast as possible. Instead, we must embrace the vision of a liveable street as a “meandering river ecosystem,” which still allows for flow but has features that support life, encourage diverse movement, and naturally regulate speed. This vision is built on three interconnected principles.

Principle 1: Design for Active Mobility These principal mandates that we create an environment where walking and cycling are the most natural, safe, and convenient choices for everyday trips. This is achieved by developing walkable, “20-minute neighbourhoods” where homes, shops, schools, and jobs are in proximity. Critically, it also requires building a connected network of high-quality, physically separated routes that give people the confidence that their safety is the number one priority, not an afterthought.

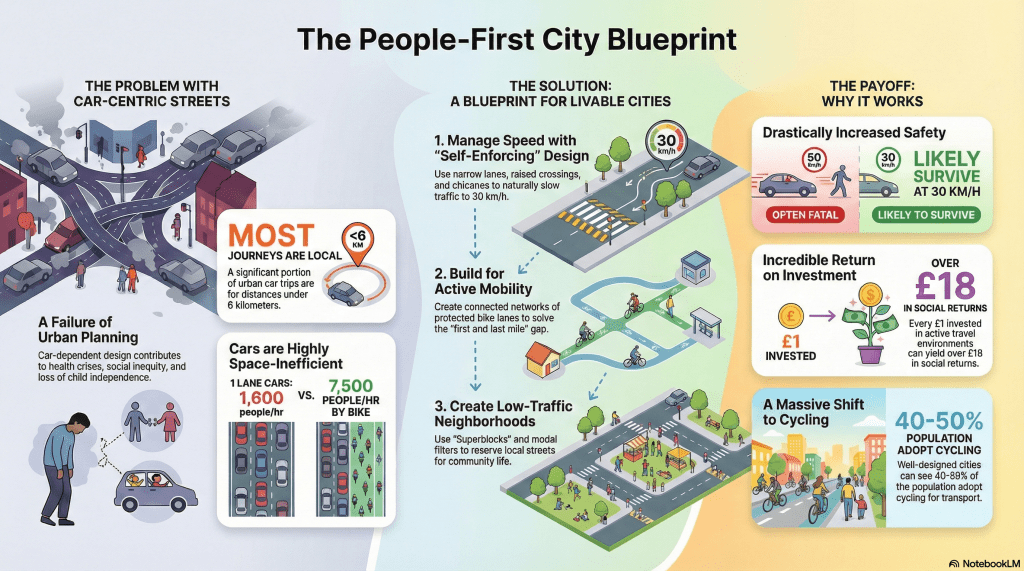

Principle 2: Engineer for Safe Speeds Human safety must be the primary engineering constraint for our streets. The physics of collisions are unforgiving: a person struck by a vehicle at 30 km/h is likely to survive, whereas a collision at 50 km/h is often fatal. This principle shifts the burden of safety from the individual to the system itself by creating “self-enforcing streets.” Through intelligent design, we can make it physically difficult for drivers to operate at unsafe speeds, rather than relying on signage and enforcement alone.

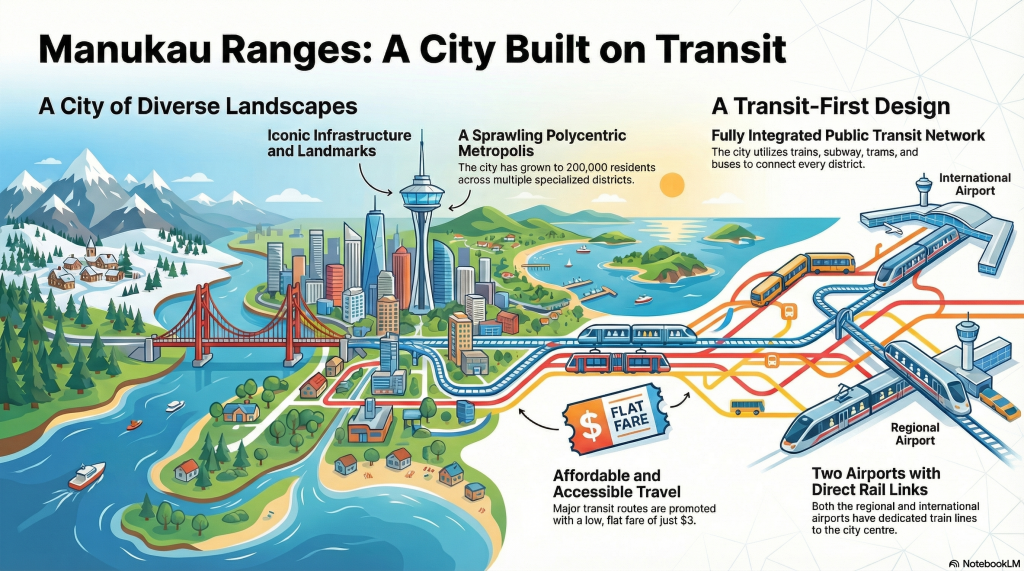

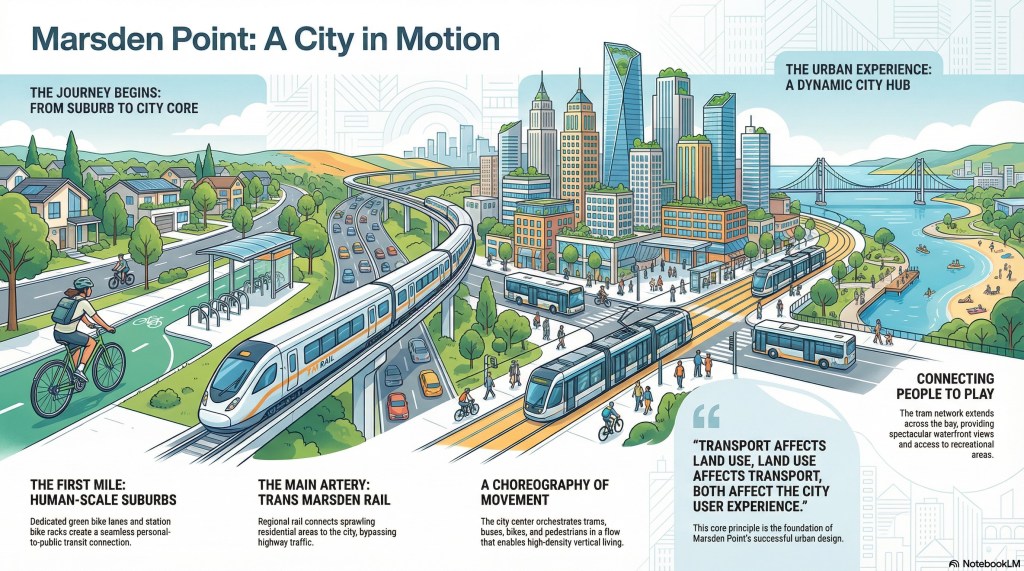

Principle 3: Integrate a Multi-Modal Network This principle leverages the unique strengths of different transport modes to create a seamless and efficient city-wide network. High-capacity public transit, such as rail and bus rapid transit, serves as the “spine” of the system, capable of moving large numbers of people over long distances. Active mobility—walking, cycling, and e-scooters—is the connective tissue that solves the critical “first and last mile gap,” efficiently connecting people from their homes and workplaces to the transit spine.

An Incredible Return on Investment

Adopting this framework is not just a social good; it is an outstanding economic investment. For every £1 invested in creating active environments that encourage walking and cycling, independent studies show a social return of over £18. This return is primarily realized through vastly improved public health outcomes and reduced healthcare costs, creating a healthier and more productive populace.

These principles provide the “why” and “what” of our proposed transformation. The following section details the “how” by outlining the specific design strategies that bring this framework to life.

4.0 A Toolkit for Transformation: Key Design and Network Strategies

This section serves as a practical guide for planners, engineers, and community leaders, presenting a toolkit of specific, proven interventions. These strategies are designed to reconfigure individual streets, intersections, and entire neighbourhood networks to align with the core principles of a people-first city.

4.1 Street and Intersection Redesign

The following “self-enforcing” design interventions physically and psychologically encourage safer driving speeds by altering the street environment.

- Narrowing Travel Lanes: Reducing vehicle travel lanes to three meters or less repurposes excess asphalt for sidewalks or cycle tracks and naturally increases driver attentiveness, which in turn reduces speed.

- Vertical and Horizontal Deflection: Interventions like speed humps, raised pedestrian crossings, chicanes (S-curves), and pinch points break a driver’s direct line of sight and force them to slow down to navigate the street comfortably.

- Tighter Corner Radii: Designing intersection corners with a small radius (1.5–5 meters) compels drivers to slow to 10–15 km/h to make a turn, eliminating high-speed cornering that endangers pedestrians.

- Daylighting: Removing on-street parking spaces immediately adjacent to crosswalks dramatically improves visibility, ensuring drivers and pedestrians can see each other clearly before a potential conflict.

- Visual Narrowing: The strategic placement of street trees, light poles, and street furniture creates a “sense of enclosure,” subconsciously signalling to drivers that they are in a complex, shared environment that requires caution.

4.2 Network-Level Management

To create truly liveable neighbourhoods, we must manage traffic flow at a network level, not just on a street-by-street basis.

- The Superblock (Urban Island) Model: This highly effective concept distinguishes between high-speed arterial roads (designed for efficient through-movement at speeds like 50 km/h) and low-speed local streets (designed for living, with speeds of 30 km/h). Through-traffic is kept on the perimeter roads, protecting the interior “island” for residents.

- Filtered Permeability: This strategy makes active travel more direct and convenient than driving for local trips. It uses modal filters—such as bollards, planters, or gates—to block cut-through car traffic (“rat-running”) on residential streets while keeping them fully accessible for people walking and cycling.

4.3 Integrated Multi-Modal Infrastructure

A successful multi-modal system depends on the seamless integration of its component parts.

- Dedicated Corridors: To be efficient and feel safe, both high-frequency public transit and cycling routes require physically separated and continuous corridors. These dedicated spaces prevent conflicts with general vehicle traffic, ensuring reliability and encouraging use by a wider demographic.

- End-of-Trip Facilities: Secure and abundant bike parking at transit stations, workplaces, and commercial destinations is a fundamental requirement, not a mere amenity. Without a safe place to store their bike, commuters will not see cycling as a viable option.

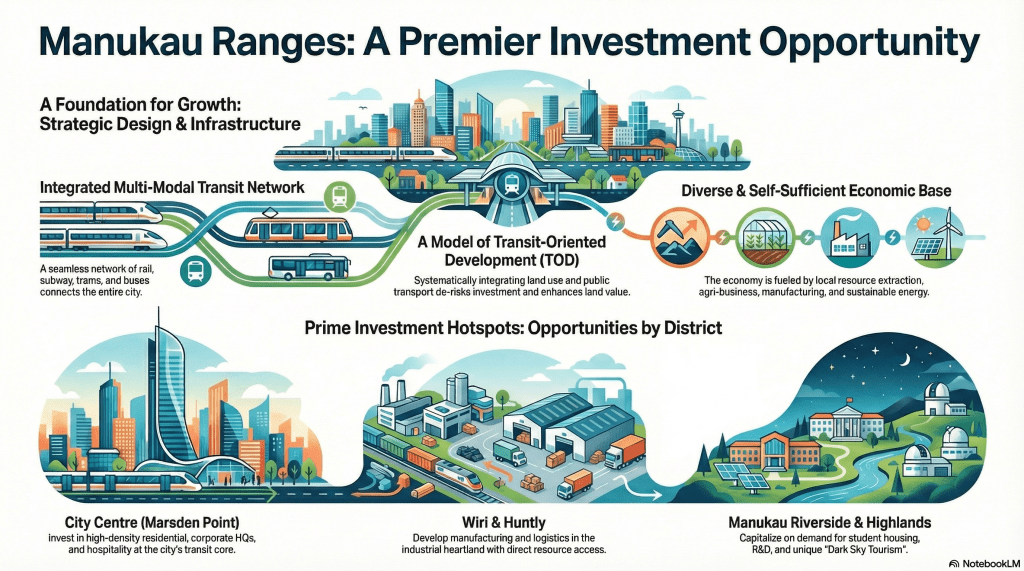

- Land Use Integration: Transportation infrastructure must be planned in concert with land use. Zoning for mixed-use, high-density development around transit hubs is critical for generating the critical mass of walkable and bikeable trips needed to support the entire system.

The availability of these powerful tools demonstrates that transformation is achievable. The ultimate step is a strategic plan for their deployment.

Posting this one again to remind us of the people first city blue print

5.0 A Phased Pathway to a People-First City

Transforming a city’s infrastructure from a car-centric model to a people-first network is a complex undertaking. It requires a deliberate, strategic, and phased approach to manage costs, build public support through demonstrated success, and ensure the long-term viability of the network.

5.1 The “Pop-up, Interim, and Capital” Framework

This standard methodology for street transformation allows the city to evaluate, learn, and adapt before committing to large-scale investment.

- Pop-up: Quick, low-cost trials using temporary materials like paint, traffic cones, and planters can demonstrate the benefits of a proposed change over an abbreviated period.

- Interim: If a pop-up is successful, an interim design using more durable materials can be installed for a longer-term data collection period. Crucially, this phase reduces public fear of change by demonstrating tangible benefits and allowing for community feedback before committing to permanent construction.

- Capital: Only after the design has been proven and refined does the city invest in permanent, high-cost reconstruction with concrete and other lasting materials.

5.2 Strategic Network Rollout

An effective rollout strategy begins where demand is highest and expands logically. Transformations should begin in the densest areas of our city, such as the city centre and around major transit hubs. From these core locations, the active mobility network should radiate outwards “stage by stage.” This incremental approach is not only practical but reflects the successful strategies observed in both real-world urban transformations and complex city simulations, where logical, network-based expansion proves most effective. The city of Nottingham, UK, provides an excellent case study of a successful strategic, city-wide network built using this principle.

5.3 Early Delivery in New Developments

For new communities, it is critical that active travel routes, public spaces, and community facilities are delivered at the very beginning of the project. If residents move in before this people-first infrastructure is in place, they will establish car-dependent habits that are incredibly difficult to break later. We must build for the desired outcome from day one.

This practical, phased approach provides a clear and manageable path toward realizing the vision of a people-first city.

6.0 Conclusion and Recommendation

The adoption of a people-first design framework offers a profound opportunity to build a healthier, more equitable, and more prosperous city. By shifting our priority from vehicle throughput to human well-being, we can reduce chronic disease, foster stronger community bonds, and build a more sustainable urban environment for future generations. This is not a theoretical exercise; it is a practical and proven path to create resilient local economies that attract and retain innovative businesses and a skilled workforce.

As we move forward, we must be guided by one essential truth: “The spaces we build end up building us. The environment we design fundamentally shapes our health, our happiness, and who we become as people.”

It is therefore formally recommended that the municipal council adopt the People-First Urban Design Framework as official policy to guide all future transportation, infrastructure, and land-use planning decisions.

So the police person’s comments in 2015 are still very unacceptable in 2026!