Best Practices Report for Developers and Architects to help deliver People First and Healthier Cities

1.0 Introduction: The Strategic Imperative of Active Design

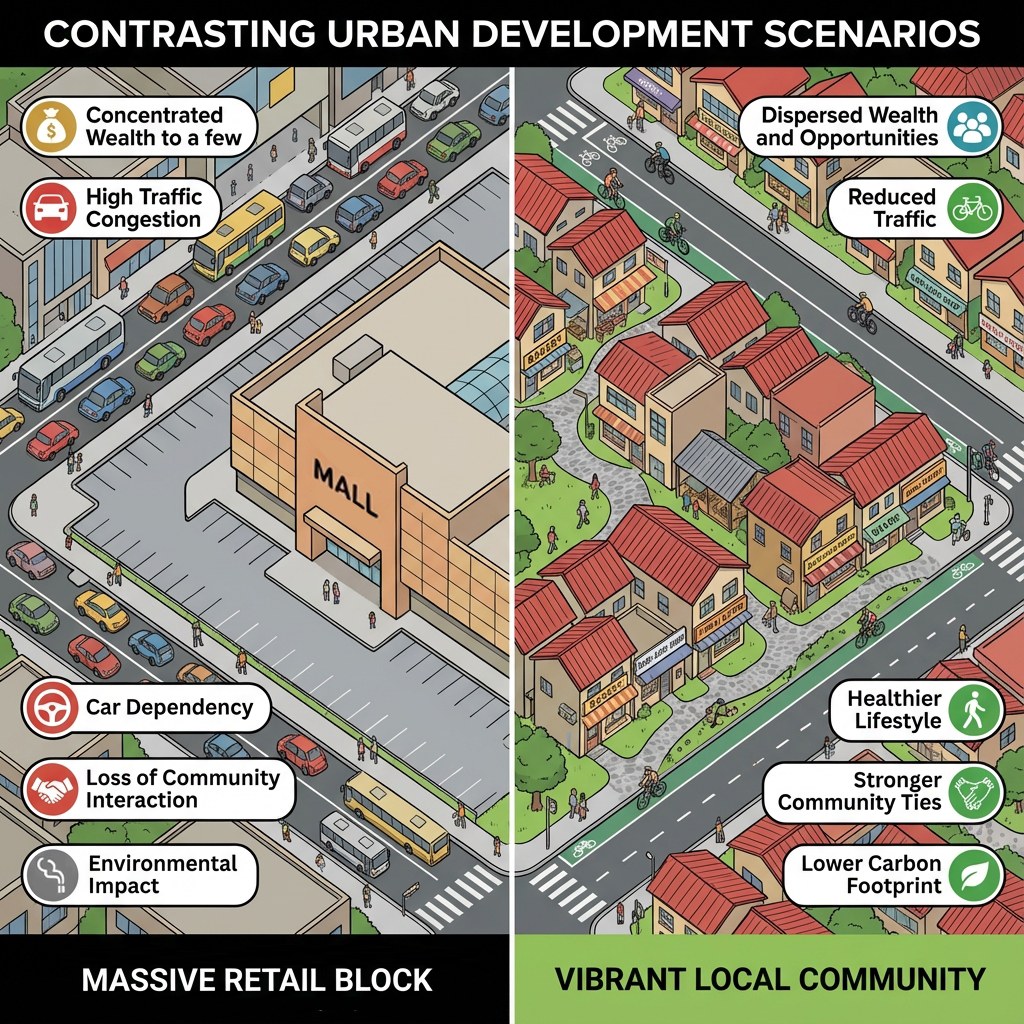

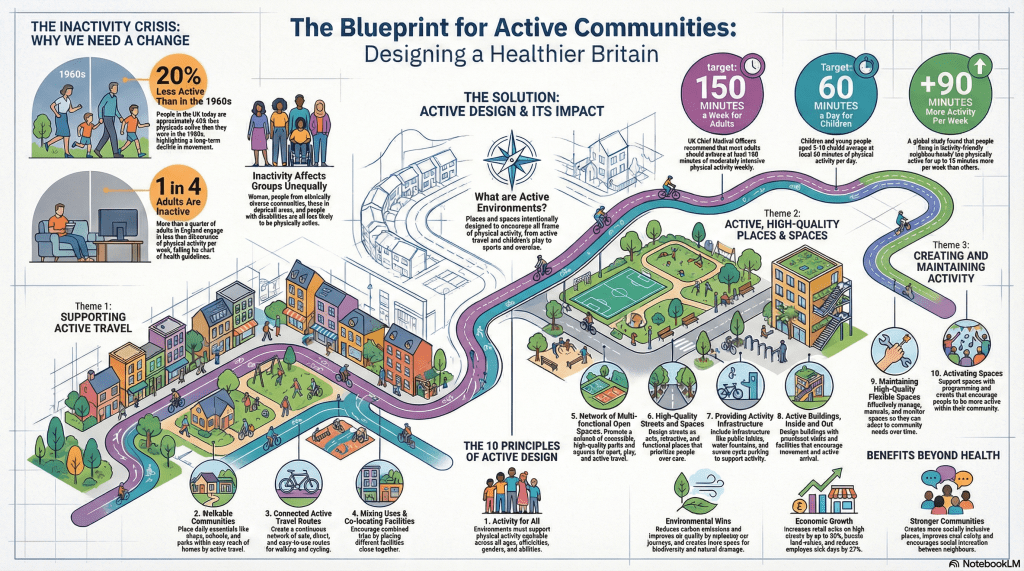

In an era of interconnected public health, environmental, and economic challenges, Active Design has evolved from a niche consideration into a strategic imperative for urban development. It is a critical framework for value creation and risk management, directly aligning with the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) goals that now define resilient and profitable real estate. Designing environments to encourage physical activity is a direct response to policy priorities for environmental sustainability, reducing inequalities, and fostering economic growth.

The core of this approach is the creation of ‘active environments’—spaces and places designed to maximize opportunities for people to be active. This concept extends far beyond formal sports facilities to encompass the full spectrum of daily life, encouraging physical activity through active travel, children’s play, outdoor leisure, and everyday movement. This holistic strategy aims to reverse a decades-long trend of designing activity out of our communities.

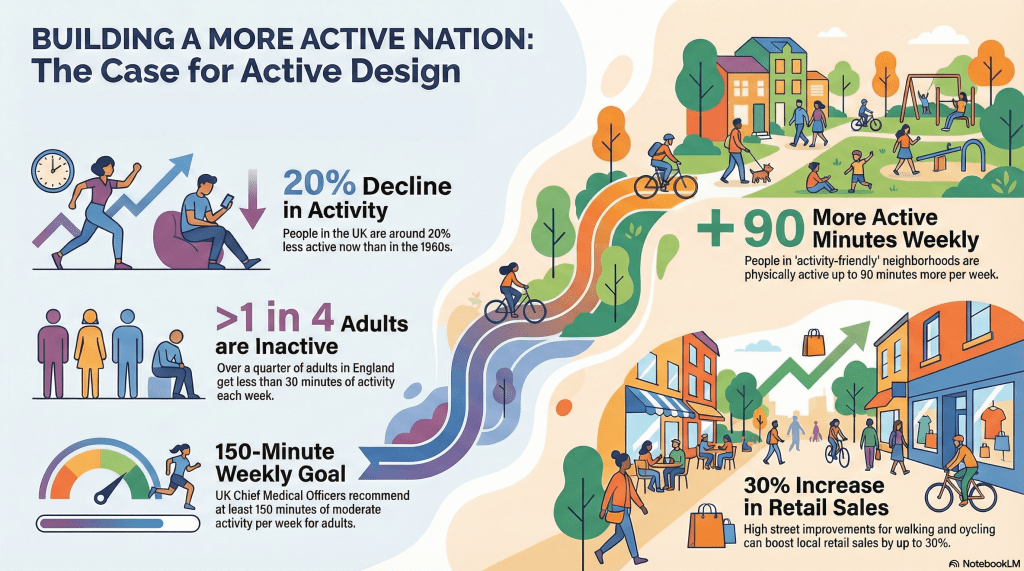

The case for creating active environments is compelling. Research across fourteen cities found that people living in ‘activity-friendly neighbourhoods’ are physically active for up to 90 minutes more per week than those who do not. This shift has cascading benefits, from improving physical and mental wellbeing to tackling climate change and fostering social equity. This report will analyse a series of successful case studies to distil actionable best practices for developers, architects, and planners seeking to implement this powerful approach. We will begin by outlining the foundational principles that underpin these successful projects.

2.0 The Ten Principles of Active Design: A Blueprint for Healthier Places

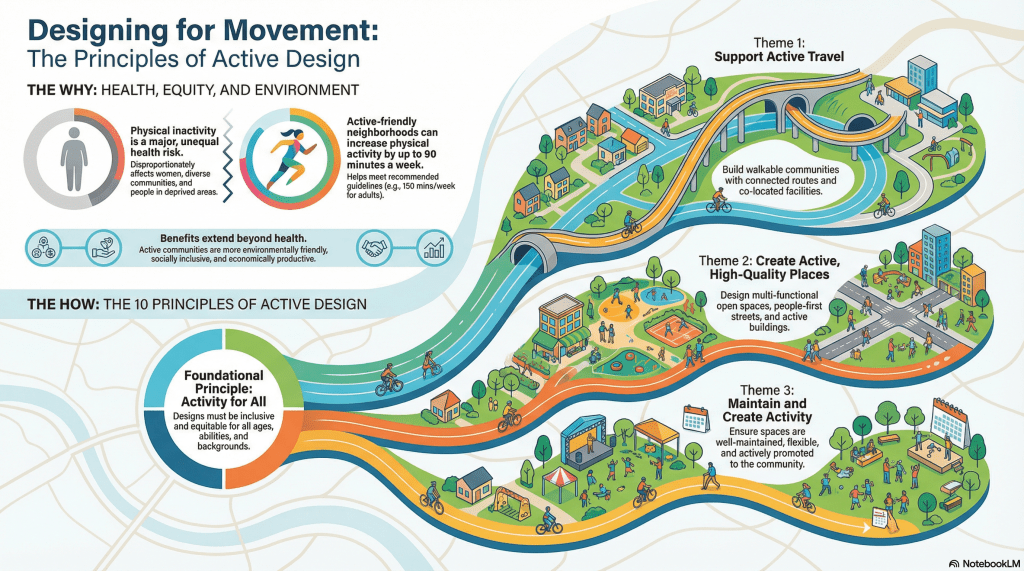

The ‘Ten Principles of Active Design’ provide a comprehensive and proven blueprint for integrating physical activity into the built environment. Developed through extensive research and stakeholder engagement, these principles offer a structured approach to creating places that are not only healthier but also more vibrant and resilient. They are organized into key themes that address different scales of development, all built upon a foundational commitment to equity.

- Foundational Principle: This principle ensures that the benefits of Active Design are shared equitably across all members of the community.

- 1. Activity for All: Design environments that support physical activity equitably across all ages, ethnicities, genders, and abilities.

- Theme 1: Supporting Active Travel This theme focuses on making active travel modes like walking and cycling the easiest and most attractive choice for everyday journeys.

- 2. Walkable Communities

- 3. Providing Connected Active Travel Routes

- 4. Mixing Uses & Co-locating Facilities

- Theme 2: Active, High-Quality Places & Spaces This theme ensures that all elements of the public realm—from buildings to open spaces—are designed to encourage movement and activity.

- 5. Network of Multi-functional Open Spaces

- 6. High-quality Streets and Spaces

- 7. Providing Activity Infrastructure

- 8. Active Buildings, Inside and Out

- Theme 3: Creating and Maintaining Activity This theme addresses the long-term success of active environments, focusing on programming, management, and adaptability.

- 9. Maintaining High-quality Flexible Spaces

- 10. Activating Spaces

These abstract principles are brought to life in real-world projects, demonstrating tangible value for both communities and developers. The following case studies illustrate how theory translates into successful practice.

3.0 Case Study Analysis: From Vision to Value

To understand the practical application and benefits of Active Design, this section analyses a diverse range of successful projects. From master-planning entire new communities to regenerating town centres and implementing city-wide infrastructure programs, these examples highlight how the Ten Principles can be adapted to various contexts to deliver measurable success.

3.1 Houlton, Warwickshire: Master-Planning a New Community for Health

- Project Overview: Houlton is a 6,200-home, residential-led development on the site of the former Rugby Radio Station. This brownfield site is being transformed into a completely new community where health, wellbeing, and physical activity are integrated at every scale, from the overarching masterplan to the details of its streets and buildings.

- Key Strategies & Interventions:

- Prioritizing Green Infrastructure: An extensive network of green open spaces and active travel routes serves as the connective tissue for the entire community, linking homes, schools, shops, and community facilities.

- Phased Delivery of Amenities: The master developer, Urban Civic, strategically delivers local centres, schools, and community facilities prior to the completion of homes. This ensures the ingredients for a walkable place are available from day one, encouraging active travel habits as soon as residents arrive.

- Diverse Activity Infrastructure: The community offers a wide variety of physical activity options beyond traditional sports pitches. This includes ‘trim trails’ with informal play and fitness equipment, newly opened allotments that are oversubscribed, community gardens, and inventive children’s play features like logs to climb on integrated into open spaces.

- Community Use Agreements: A community use agreement with the secondary school allows residents and sports clubs to access its sports hall. A similar agreement allows the primary school to use the swimming pool at a new on-site commercial gym, maximizing the utility of these assets.

- Outcomes & Lessons Learned:

| Key Outcome | Lesson for Developers |

| Higher sales rates and increased sales values compared to the surrounding area. | Investing in long-term quality and a higher quality of life is a direct driver of commercial success. This replicable strategy is being deployed by Urban Civic across its fourteen development sites in England. |

| High participation in community activities and use of facilities like allotments and open spaces. | The open space network is the core placemaking element that enables successful physical activity interventions. |

| A flexible masterplan that allowed the location of a local centre to be rethought based on the success of an early pop-up café. | An ongoing, flexible approach allows for adaptation to changing trends and resident feedback, creating a better product. |

3.2 Stevenage Town Centre: Regenerating a New Town Core

- Project Overview: As the UK’s first post-war New Town, Stevenage is undergoing an ambitious regeneration program to rejuvenate its centre. The plan introduces new homes, jobs, and facilities within a public realm that prioritizes walking and cycling, building on “the active and healthy behaviours that were the original attraction of these places for new residents post-World War Two.”

- Key Strategies & Interventions:

- Reclaiming the Street Network: The project includes upgrading the underused segregated cycleway network, improving underpasses for safety, and planning to downgrade the Lytton Way dual carriageway into a more pedestrian-friendly ‘urban boulevard’.

- Activating Space Through Temporary Use: The “Event Island Stevenage” project is using the site of the former bus station as an ‘urban lab’. Before its final development as a ‘garden square’, the space is being used to evaluate different temporary uses—including sports events, trampolines, and a covered ice rink—to see what is successful.

- Repurposing Infrastructure: The bus station was relocated closer to the railway station, a move that released centrally located land near the Town Square. This space is now being used for improved public realm and active uses.

- Enhancing Identity and Wayfinding: A Heritage Trail featuring a series of ground plaques is being established to celebrate the town’s unique New Town history and encourage walking tours of its key sites and artwork.

- Outcomes & Lessons Learned: The Stevenage project demonstrates that a clear, guiding masterplan provides the certainty needed to align multiple partners and stakeholders around a shared vision. Furthermore, making early, visible improvements to the public realm and creating opportunities for physical activity can generate wider investment interest, transforming a town centre into a desirable mixed-use destination.

3.3 Nottingham: A City-Wide Active Travel Transformation

- Project Overview: Nottingham is implementing an ongoing, city-wide program to transform its streets for active travel. Funded by the Department for Transport’s Transforming Cities Fund, the initiative integrates an extensive network of new segregated cycle routes with significant public transport upgrades.

- Key Strategies & Interventions:

- Strategic Network Design: A comprehensive strategic plan was created to deliver a fully connected network of on-street cycle routes. Corridors were prioritized based on deliverability and local benefits, with a focus on areas with higher levels of deprivation.

- High-Quality, Consistent Infrastructure: The routes are designed to a high standard, typically as segregated two-way tracks on main roads. A consistent design language, such as the use of green paint where cycleways cross side roads, makes cyclist priority clear and the network easy to understand.

- Reclaiming the City Centre: Private motor vehicles have been removed from key streets, such as Canal Street, to eliminate a significant barrier between the city centre and the rail station. This has created new pedestrian/cyclist-only zones and high-quality civic spaces.

- Outcomes & Lessons Learned: Nottingham’s success highlights a critical lesson: delivering continuous, connected corridors is far more effective than implementing piecemeal improvements. A clear, ambitious strategic plan—underpinned by official tools like the DfT’s Active Mode Appraisal Toolkit and validated by bodies like Active Travel England—provides a framework that aligns both public infrastructure investment and private development aims, ensuring that new projects contribute to a cohesive city-wide network.

3.4 Aspire@ThePark, Pontefract: A Hub for Community Health

- Project Overview: Aspire@ThePark is a modern community and sports facility co-located within a public park. It offers a diverse range of facilities under one roof, including a 10-lane swimming pool, a gym, fitness studios, a climbing wall, and a public café.

- Key Strategies & Interventions:

- Flexible, Multi-Use Design: The facility is designed for maximum flexibility. The 10-lane pool is large enough to allow public swimming to occur simultaneously alongside school lessons without conflict. The outdoor tennis courts are also used weekly by a local cycle training scheme for lessons and proficiency testing.

- Integration with the Outdoors: The facility is seamlessly connected to the wider park. Users frequently combine indoor activities at the centre with running the popular loop around the adjacent racecourse. The facility also encourages activity in its surroundings by renting out equipment such as running buggies.

- Resolute Activation Staff: The operator employs not just service staff but also dedicated ‘Activators’ who are responsible for programming the spaces. These activators work closely with local health practitioners and commissioning services to deliver social prescribing programs, such as cardiovascular rehabilitation sessions.

- Outcomes & Lessons Learned: The success of the Aspire@ThePark model lies in a dual investment. First, it prioritizes creating highly flexible spaces that can adapt to evolving community needs and original activity trends. Second, it demonstrates that investing in programming and activation staff is just as crucial as the capital investment in the physical building, ensuring the facility remains a vital and responsive community asset.

These examples, while diverse in scale and context, reveal a set of common strategies that are central to the successful implementation of Active Design.

4.0 Cross-Cutting Best Practices for Implementation

While each project is unique, a clear set of transferable best practices emerges from their collective success. These practices provide a strategic guide for developers and architects seeking to embed Active Design principles effectively, moving from policy aspiration to on-the-ground value creation.

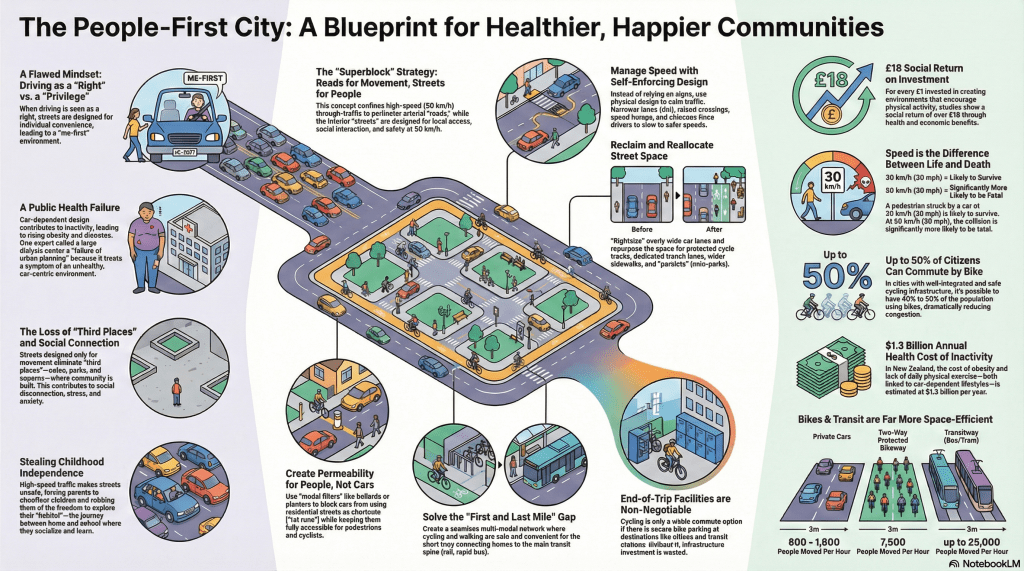

4.1 Practice 1: Develop People-Centric Networks, Not Piecemeal Paths

The critical factor for encouraging active travel is connectivity. Creating continuous, safe, and direct networks that connect homes to key destinations like schools, shops, and employment delivers the greatest value. The case studies reveal two effective models: the city-wide strategic network seen in Nottingham, which aligns public and private investment over a large area, and the master-planned community network in Houlton, which creates a complete, high-quality environment from day one within a self-contained site. In contrast, the impact of isolated or disconnected paths is severely limited, as they fail to provide a genuine alternative for complete journeys.

4.2 Practice 2: Co-locate and Phase for Early Activation

Strategic co-location and phasing of facilities can profoundly influence behaviour. The Houlton case study powerfully demonstrates that delivering community facilities, local centres, and schools early in the development process establishes active travel as a default habit for new residents from day one. Similarly, the Aspire@ThePark project shows how co-locating a sports facility within a public park creates a destination with linked trip opportunities. This constructive collaboration boosts the viability of both the facility and the park, creating a hub of community activity.

4.3 Practice 3: Design for Equity and Social Value

Making “Activity for All” a foundational principle is essential for creating tremendously successful places. This means designing inclusive spaces that cater to different ages, abilities, and genders, and actively addressing health inequalities, as seen in Nottingham’s prioritization of cycle routes in more deprived neighbourhoods. Crucially, this approach also mitigates existing environmental injustices. Reducing traffic through active travel design disproportionately benefits deprived communities, which “are more likely to be located on or adjacent to major roads.” This commitment to equity does more than tackle health disparities; it fosters community connection and builds long-term social value.

4.4 Practice 4: Program and Manage for Long-Term Vitality

Capital investment in physical infrastructure must be matched by a commitment to long-term activation and management. The ‘Activators’ at Aspire@ThePark, who run social prescribing programs, exemplify how staffing is critical to a facility’s success. Furthermore, the temporary ‘urban lab’ approach at Stevenage demonstrates a key risk-mitigation strategy for developers: testing different uses with low-cost, temporary installations to see what is successful before committing to significant capital expenditure. Programming, monitoring, and maintaining spaces ensures they remain valued, safe, and responsive to community needs throughout their entire lifespan.

These best practices form the foundation of a robust business case for adopting an Active Design approach.

5.0 Conclusion: The Compelling Business Case for Active Design

For developers and architects, embracing Active Design is not an altruistic gesture but a shrewd business decision that aligns with market demand and long-term policy trends. The evidence from the case studies demonstrates a clear and compelling value proposition that goes beyond simple public health benefits. Adopting these principles delivers tangible returns and creates more resilient, valuable assets.

- Enhanced Commercial Returns: High-quality, walkable communities with excellent amenities are what the market desires. The Houlton case study provides direct evidence that developments incorporating Active Design principles can command higher sales values and achieve faster sales rates than competing projects in the surrounding area. This is a direct result of creating a superior quality of life that residents are willing to pay a premium for.

- Future-Proofing Assets: Development that aligns with major policy priorities—including public health, climate resilience, and social equity—is inherently more resilient and attractive for long-term investment. Crucially, such projects are de-risked during the planning process, as they “demonstrate clearly how planning applications support Local Plan policies.” As regulations and public expectations evolve, assets built on Active Design principles will be ahead of the curve, enhancing their appeal to funders, partners, and future buyers.

- Creating Lasting Placemaking Value: Ultimately, Active Design is not an additional expense but a foundational investment in placemaking. It is the practice of creating desirable, healthy, and vibrant places where people genuinely want to live, work, and play. This intrinsic desirability is the ultimate driver of long-term asset value, ensuring a project’s relevance and success for decades to come.