Will the Planning Bill and Standardised Zones represent a new way forward?

For the past month I have been running a Ben Goes Planning series covering all sorts of urban interventions that could be done to make cities, towns, metropolitan centres, and suburban areas places for people rather than cars. Through the series there has been an underlying theme lurking all the way through it. The state of the Planning Regime in Aotearoa, present and future.

Because in the Ben Goes Planning series, New Zealand’s old planning regime – the Resource Management Act (which disables a lot of what is proposed) needed to be replaced (to enable a lot of what was proposed). Thus it is fitting to bring the Ben Goes Planning series to a close with a transition over to the Planning Reforms that would again enable a lot of what proposed. At the same time also including what tweaks need to be made to the Planning Bill to get it from good to perfect!

Recoding our Cities in Aotearoa, the nuts and bolts of the Planning Bill

With that I will leave the opening to my then draft submission to the Planning Bill. It is one of five different parts to the entire submission which covers different aspects of the Bill, and where I would like the Bill to ultimately land. I will post the full submission after it is lodged with Parliament by February 13, 2026.

Summary of the Planning Bill, introducing the submission

(Draft) Main Submission: An Analysis of New Zealand’s Planning Bill: Strengths, Opportunities, and Challenges for Urban Development and Resilience

Introduction: A Generational Shift in Planning Philosophy

The replacement of New Zealand’s Resource Management Act (RMA) represents a monumental legislative overhaul, fundamentally reconstructing the principles that have governed land use, development, and environmental management for over three decades. The 30-year-old RMA had become widely regarded as slow, overly complex, and inconsistent in its application across the country. Its decentralized, project-by-project approach to assessing environmental effects proved paralyzing, making it notoriously difficult, expensive, and time-consuming to build anything from household renovations to vital national infrastructure.

The new Planning Bill marks a complete philosophical inversion of the previous regime. It dismantles the decentralized, effects-based model and erects a new, centralized, top-down, and outcomes-focused architecture. This analysis seeks to evaluate the Strengths, Opportunities, and Challenges presented by the new Planning Bill. It will focus specifically on the legislation’s potential to deliver people-first cities, enable the development of resilient infrastructure, and integrate initiative-taking hazard management into the core of regional and national strategy.

The Bill’s entire framework is an attempt to resolve a core tension that lies at the heart of modern governance. It poses the central question: “Can you enable rapid development and significant economic growth while at the same time strengthening environmental, cultural, and community safeguards?”

1. The New Architecture: From Project-by-Project Litigation to Strategic, Top-Down Direction

The strategic importance of the Planning Bill’s new structural framework cannot be overstated. It is a direct and deliberate response to the “endless relitigating cycle” that plagued the RMA, designed to front-load debate, lock in certainty, and prevent the same arguments from being re-judged at every stage of the development process. This is achieved through a hierarchical system where decisions made at a higher strategic level are binding on all subsequent levels.

The Bill establishes a four-level “hierarchical funnel framework” that channels decision-making from high-level national goals down to the implementation of individual projects:

- Goals: At the top of the funnel are the high-level outcomes that the system must achieve. These are tightly defined and fixed within the Bill itself, serving as the foundational principles for all subsequent planning and decision-making.

- National Instruments: Central government provides binding direction through National Policy Directions (NPD) and National Standards. These instruments translate the high-level goals into mandatory, uniform rules and methodologies, ensuring consistency across the country and resolving potential conflicts between competing objectives.

- Regional Combined Plans: For the first time, every region will have a single, integrated plan. This plan is comprised of three parts: a Regional Spatial Plan setting a 30-year strategic direction, a land use plan, and a natural environment plan. This level must implement the direction set by the National Instruments.

- Consents and Permits: At the bottom of the funnel is the final implementation stage for individual projects. This stage is intended to be faster and more efficient, as the strategic and substantive matters will have already been decided and locked in at the higher levels of the framework.

This new architecture fundamentally shifts the nature of public engagement. Under the RMA, communities often fought development battles at the individual consent stage. The new system requires engagement at the high-level strategic planning phase, forcing debate to occur early in the process. Once these strategic battles are fought and won, the final consent stage becomes a simpler, faster, and less litigious exercise in implementation.

2. Assessed Strengths of the Planning Bill

The primary strengths of the Planning Bill are best understood as targeted solutions designed to rectify the most critical and well-documented failures of the previous RMA system: a chronic lack of speed, clarity, and consistency. The new architecture introduces powerful mechanisms to drive certainty, unlock national priorities, de-risk development, and provide legal continuity for existing rights and agreements.

2.1. Driving Certainty, Speed, and Consistency

The Bill’s core architecture is engineered to deliver certainty. Its foundational principle is that once an issue is settled at a higher strategic level—whether in a National Instrument or a Regional Spatial Plan—that decision is binding all the way down the funnel, reducing the relitigating of matters that have already been decided.

To enforce this, the Bill includes a powerful incentive structure that strongly encourages local councils to adopt Standardised Provisions when creating their land use plans. This creates an obvious choice with significant legal and financial consequences.

| Provision Type | Process and Consequences |

| Option 1: Standardised Provisions | Adopts rules from a predefined national set. The reward is described as “immense”: speed, simplicity, and appeals limited to questions of law, not the substance of the rule. |

| Option 2: Bespoke Provisions | Creates unique local rules. The penalty is a mandatory justification report and full exposure to costly, merits-based appeals in the Environment Court. |

This dual-pathway system acts as a “very clever lever,” pushing the entire planning system towards national standardization. By making the bespoke option legally perilous and expensive, it creates a powerful incentive for councils to align with national direction, thereby reducing the “chaotic patchwork system” of local rules and the costly litigation it generated.

2.2. Unlocking Strategic National Priorities

The Bill carries an explicit dual mandate to balance safeguards with a clear objective to unlock stalled capacity for development and infrastructure. It is designed to be an enabling piece of legislation, targeting key areas of national importance that struggled for momentum under the previous system. The specific development priorities it aims to facilitate include:

- Increasing capacity for housing and business growth, which has been severely constrained for years.

- Prioritizing high-quality infrastructure.

- Achieving the explicit national goal to double renewable energy capacity.

- Supporting primary sectors like aquaculture, forestry, and mining that faced significant delays under the RMA.

2.3. De-risking Development by Narrowing Regulatory Scope

In a radical departure from the RMA’s “effects-based philosophy,” where all potential effects of a project could be grounds for opposition, the new Bill explicitly legislates certain subjective and private interests “right out of existence.” Decision-makers are now legally required to disregard a specific list of effects, fundamentally changing the grounds upon which a development can be challenged.

According to the Bill, the following effects must now be disregarded:

- General visual, amenity, and aesthetic qualities.

- The impact of a development on private views from private property.

- Effects on business competition.

- The internal site design and layout of a project.

- The effect of a proposal setting a precedent.

The impact of this change is profound. For example, a new house that is considered ugly and blocks a neighbour’s view is now explicitly defined as a private issue, not a planning issue that can be used to stop the project. This narrowing of regulatory scope is designed to de-risk development by eliminating the “death by a thousand cuts” opposition strategy, where a cumulative case for refusal was built upon numerous subjective complaints.

2.4. Guaranteeing Protections for Treaty Settlements

The Bill includes explicit provisions to uphold the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. It establishes a dedicated goal for Māori interests covering participation in the development of plans, the protection of significant cultural sites (such as wāhi tapu), and the enablement of development on identified Māori land.

Crucially, the legislation contains a commitment to ensure that Treaty settlement redress maintains the “same or equivalent effect” under the new act. This guarantee is a vital provision for legal continuity and certainty. It insulates existing rights and agreements from being eroded by the legislative rewrite, ensuring that the Crown’s responsibilities are upheld and providing confidence for Māori authorities who rely on these settlements for investment and governance.

3. Potential Opportunities for People-First and Resilient Cities

While the Planning Bill provides a new procedural framework, its greatest potential lies in how that framework is used to address contemporary urban challenges. The Bill’s centralized, top-down structure creates significant opportunities to implement modern urban planning principles at a national scale—a task that was effectively impossible under the fragmented RMA system. This section explores how the Bill’s mechanisms could be leveraged to create people-first cities, build resilient infrastructure, and plan proactively for natural hazards.

3.1. Opportunity: A National Vehicle for Green and People-First Urbanism

The new system of binding National Standards and Standardised Zones creates a powerful vehicle for implementing progressive urban planning concepts nationwide. Where the old “chaotic patchwork system” hindered consistent application of best practices, the new framework allows for their direct integration into the mandatory rulebook for every local council that chooses the standardized, fast-track option.

This creates the potential for National Instruments to incorporate established methodologies for creating healthier, more liveable urban areas. For instance, principles such as the 3-30-300 green infrastructure rule (ensuring universal access to green space) or People First design concepts (prioritizing walkability and human-scale development) could be codified into national standards. This centralized mechanism could dramatically accelerate the transition to the “well-functioning urban and rural areas” envisioned as a key goal in Clause 11 of the Bill.

3.2. Opportunity: Initiative-taking Planning for Natural Hazard Resilience

The Bill mandates that Regional Spatial Plans (Clause 27) must set a strategic direction for a region for a period of at least 30 years. This long-term, strategic focus provides a critical opportunity for initiative-taking resilience planning. This aligns with an explicit goal of the new system to reduce risks from natural hazards, which are defined in the Bill (Clause 3) to include the effects of climate change.

Instead of considering climate adaptation and hazard mitigation on a reactive, project-by-project basis, the spatial planning process provides a forum to integrate these considerations into the core of a region’s long-term development strategy. This front-loaded, strategic approach allows for better-coordinated decisions on public investment, land use, and infrastructure priorities to build genuine, long-term resilience to climate change and other natural hazards.

3.3. Opportunity: Adopting Modernized Zoning Principles

The Bill’s strong incentive to move away from a bespoke, locally defended zoning system towards nationally Standardised Zones presents a unique opportunity to adopt more efficient and flexible land-use frameworks. The new structure is highly conducive to implementing principles from successful international models.

For example, the Japanese planning model, which often uses broader, effects-based zoning categories, allows for a greater mix of uses within zones and enables cities to respond more dynamically to market demands. Adopting such principles through national standardization could help achieve the Bill’s stated goal of enabling “competitive urban land markets” (Clause 11) by reducing rigid, single-use zoning and allowing for more organic, mixed-use development.

4. Identified Challenges and Potential Risks

The Planning Bill’s ambitious reforms are built upon a series of significant trade-offs. While the goal of a faster, more certain, and consistent system is laudable, the new centralized model introduces a distinct set of challenges and risks. If not carefully managed, these risks could undermine the legislation’s success and create new forms of complexity and conflict.

4.1. Challenge: The Local Democracy and Efficiency Trade-Off

At the heart of the Bill lies a “massive trade-off”: the system exchanges the ability for local communities to argue the specific merits of a rule for their town in return for national speed and efficiency. By legally penalizing “bespoke” local rules with the prohibitive cost and risk of merits-based appeals and limiting appeals on “standardised” rules to narrow points of law, the Bill inherently diminishes the role of local democratic input on the substance of planning. The old system may have given too much weight to subjective local arguments, leading to inertia, but the new system risks swinging the pendulum too far, prioritizing centralized efficiency at the expense of local voice and context.

4.2. Challenge: The Risk of Centralized Failure

The entire “hierarchical funnel framework” is critically dependent on the quality, clarity, and wisdom of the top-level National Instruments—the National Policy Direction and National Standards. The system’s success hinges entirely on these documents being well-designed, unambiguous, and effective. This raises a critical question: if these high-level rules are unclear, vague, or poorly drafted, could the old problems of complexity, cost, and relitigating simply move up to a higher, more impactful level of the system? A failure at the national level would cascade down through the entire framework, potentially creating more paralysis than the system it replaced.

4.3. Challenge: A New Battleground Over “Minor” Effects

The Bill introduces new, higher assessment thresholds that are likely to become a significant source of conflict. Under the new rules, an adverse effect that is deemed “less than minor” will not be considered by a consent authority, and public notification of a project will only occur if adverse effects are determined to be “more than minor.”

With many subjective criteria like visual amenity and private views now explicitly removed from consideration, the real power in the new system will lie in the definition and interpretation of what constitutes a “more than minor” effect on a legally protected value. This definition will become the new battleground for disputes and litigation, as opponents and proponents of development focus their arguments on this critical, and potentially ambiguous, threshold.

5. Conclusion: Navigating the Policy Tightrope

The Planning Bill represents a fundamental philosophical shift in New Zealand’s approach to land use and development. It moves away from the adversarial, decentralized, project-by-project litigation system of the RMA towards an outcomes-focused, standardized framework where major debates are front-loaded to the strategic planning stage.

The Bill’s core strengths lie in its clear ambition to deliver the speed, certainty, and consistency that the previous system so conspicuously lacked. It creates significant opportunities to implement modern, strategic planning for resilient, people-focused, and sustainable urban environments on a national scale. However, these opportunities are accompanied by considerable challenges. The trade-off between national efficiency and local democracy is profound, and the system’s success is critically dependent on the quality and clarity of the national-level direction that will guide it.

The success of this monumental reform—what can be described as the “ultimate policy tightrope walk”—will not be determined by the elegance of the legislative framework itself. It will be determined by the wisdom, clarity, and foresight embedded in the national-level decisions that will flow through this new architecture to shape the future of New Zealand’s built and natural environments.

Summary of where I would like the Bill to land via the combined submission

Submission: A New Blueprint for Aotearoa: Implementing a Resilient Urban Habitat Model

1.0 A Strategic Pivot: From ‘Grey Inertia’ to a Resilient Urban Operating System

For decades, Aotearoa New Zealand’s urban development has been defined by a state of “Grey Inertia”—a condition of bureaucratic stagnation and reactive mitigation that has throttled national productivity. The legacy planning system, governed by the Resource Management Act (RMA), created a “Postcode Lottery” of over 1,175 fragmented and often incompatible local zones. This chaotic framework has incurred significant “Regulatory Debt,” defined as the compounding engineering inefficiencies and fiscal liabilities caused by decades of unplanned sprawl. This debt manifests as underutilized “asphalt deserts” and the “Nitpicking Trap,” a culture of wasting professional expertise on subjective details like door handles instead of strategic city-building.

The proposed Aotearoa Planning Bill 2025 marks a fundamental system upgrade. It is not a minor adjustment but a complete rewiring of our urban architecture, moving from a subjective, fragmented process to an objective, standardized framework. The following table contrasts the two systems, illustrating the scale of this strategic pivot.

| Dimension | Legacy System (RMA 1991) | 2025 Planning Bill Framework |

| Decision-Making | Subjective “Culture of Permission”: Characterized by “death by a thousand cuts” via private objections and project-level litigation. | Objective “Culture of Adherence”: Employs standards-based planning to achieve measurable, strategic outcomes. |

| Regulatory Structure | Fragmentation: A patchwork of 1,175+ disparate local zones with inconsistent and incompatible rules. | Standardization: A universal national codebase of 17–20 National Standardised Zones (NSZs). |

| Operational Focus | Reactive: Focused on the reactive mitigation of unplanned sprawl and the localized effects of individual projects. | Initiative-taking: Implements infrastructure-led growth guided by 30-year national and regional spatial horizons. |

| Public Input | Downstream: Public input and conflict are concentrated at the project-consent stage, causing delays and uncertainty. | Upstream: Strategic input is front-loaded into the blueprint stage (national and regional plans), de-risking delivery. |

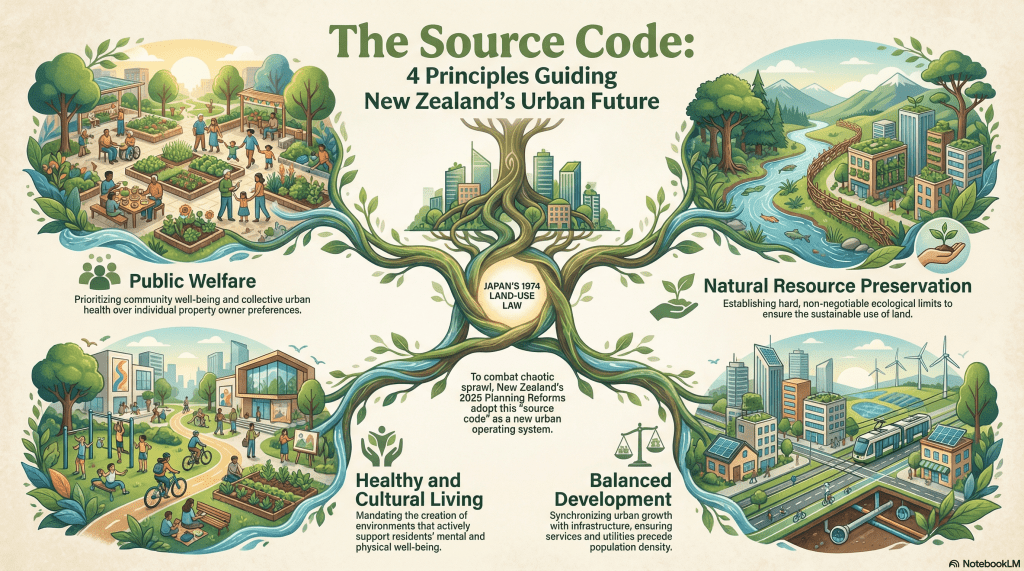

This document serves as a strategic briefing on how the Aotearoa Planning Bill 2025 imports the structural “DNA” of Japan’s successful 1974 Land-Use Law. The goal is to install a resilient “urban operating system” capable of managing growth, enhancing environmental quality, and providing the legal certainty required for national progress. The philosophical core of this new system is built upon four foundational principles that shift the focus from individual property preferences to the long-term well-being of the collective habitat.

2.0 The Source Code: Four Foundational Principles for a Resilient Aotearoa

Effective urban development requires a clear philosophical framework to guide every decision, from national strategy to local implementation. The Aotearoa Planning Bill 2025 is anchored by four foundational principles synthesized directly from Japan’s 1974 Land-Use Law. This legislation was originally drafted to combat the acute pressures of population concentration, speculative land investment, and chaotic development—challenges that are strikingly familiar in modern Aotearoa. These principles provide the new system with its moral and strategic compass.

2.1 Public Welfare

This principle represents a fundamental ideological shift from a legal tradition where “Property Rights Supreme” to one where “Public Welfare Supreme.” It establishes that the collective urban health and well-being of the community take precedence over the preferences of individual property owners. It moves away from a system where subjective concerns like private views could stall essential development, toward one that prioritizes outcomes that benefit the entire community, such as housing availability, public health, and environmental quality.

2.2 Natural Resource Preservation

This principle mandates the establishment of hard, non-negotiable ecological limits to ensure the sustainable use and protection of land and natural resources. Instead of treating environmental factors as considerations to be “balanced” or traded away, this embeds them as foundational constraints within which all development must occur, ensuring the long-term health of our natural capital.

2.3 Healthy and Cultural Living

This principle acts as a mandate to create environments that actively support the mental and physical well-being of residents. This goes beyond mere aesthetics; it is grounded in science, such as Attention Restoration Theory (ART), which demonstrates the restorative mental health benefits of exposure to nature. The framework uses this principle to engineer green space and natural elements into the urban fabric as a core requirement for a healthy population.

2.4 Balanced Development

This principle synchronizes urban growth with infrastructure-led planning, institutionalizing the mantra of “Pipes before People.” It ensures that population density is only unlocked where essential services, utilities, and transport networks are already in place or are guaranteed to precede development. This initiative-taking sequencing prevents the fiscal strain of unplanned infrastructure extensions and ensures that new communities are functional and sustainable from day one.

Together, these principles form the source code for a new urban operating system. The following sections detail the practical mechanisms—the “skeleton”—designed to translate this philosophy into a functioning, resilient reality.

3.0 The Skeleton of Growth: Managing Land, Resources, and Sprawl

To enact the four foundational principles, the new planning system requires a strategic “Skeleton” for growth. This is delivered through the “Urban Dam” model, the primary mechanism for spatial and fiscal management. This model is designed to control the “Hydraulic City” effect—a phenomenon where rising land values and wealth in the urban core create immense pressure that pushes working-class residents to unserviced, car-dependent fringes. The Urban Dam provides the structural control needed to manage this pressure, stop speculative sprawl, and channel growth into productive, resilient patterns.

3.1 The ‘Urban Dam’: A Stop Valve for Sprawl

The Urban Dam is a binary spatial system that provides clear, unambiguous signals to the market, stabilizing land values and directing investment. It consists of two core components:

- Urbanisation Promoting Areas (UPAs): These are designated 10-year growth “reservoirs” where public investment in infrastructure—such as sewage, streets, and transit—is legally prioritized. By channelling development into these serviced areas, the system ensures that growth capacity is unlocked only where planned utility exists.

- Urbanisation Control Areas (UCAs): These function as “dam walls” where urbanization is prohibited in principle. By signalling that these areas are a low priority for new infrastructure investment, the system effectively kills the speculative value of rural fringe land. This stops speculative land-banking and halts sprawl dead in its tracks.

The fiscal and environmental benefits of this model are profound. It liquidates the “regulatory debt” of past sprawl by preventing the creation of new, inefficient “asphalt deserts.” By tying land value to actual utility rather than speculative hope, the model protects Aotearoa’s productive rural land and provides the finance and construction industries with a predictable 10-year development pipeline.

3.2 The Standardization Revolution: A Universal Language for Development

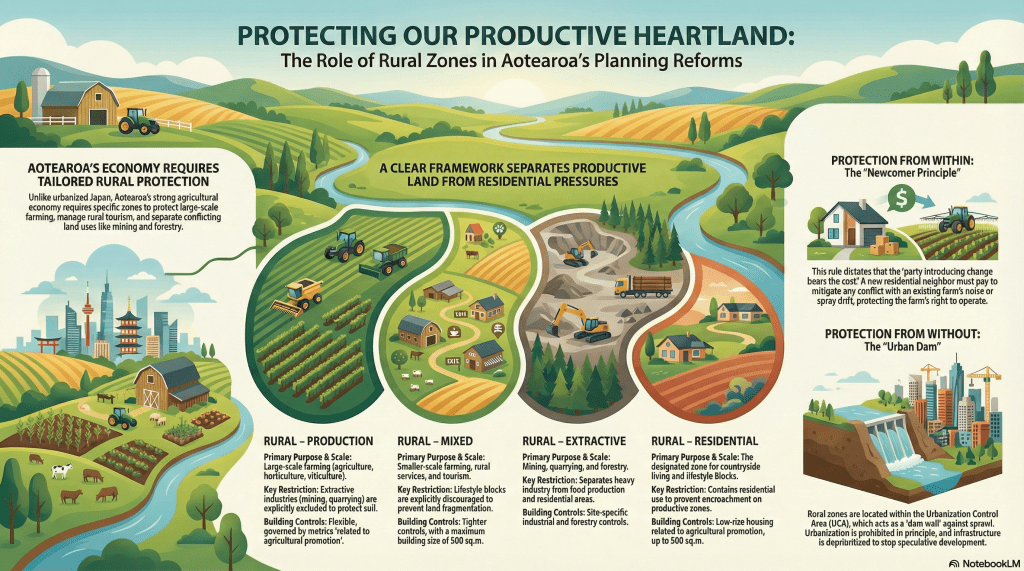

A core component of this new skeleton is the radical simplification and standardization of zoning rules. The system replaces the “postcode lottery” of over 1,175 fragmented local zones with 17-20 National Standardised Zones (NSZs). This revolution, directly inspired by Japan’s 13-zone framework, creates a universal, easy-to-read language for the development industry, enabling it to operate at a national scale.

However, recognizing Aotearoa’s unique economic geography, the framework includes critical rural adaptations that are absent in the highly urbanized Japanese model. These specialized rural zones are designed to protect our primary industries:

- Rural-Production: Reserved for large-scale farming, including agriculture, horticulture, and viticulture, protecting this land from fragmentation.

- Rural-Mixed: Allows for smaller-scale farming, rural service industries, and tourism, while explicitly discouraging the creation of lifestyle blocks that fragment productive land and strain public services.

- Rural-Extractive: Provides dedicated zones for mining, quarrying, and forestry, using overlays to manage resource extraction in a targeted and predictable manner.

This structured “Skeleton” provides the certainty and control needed to manage growth effectively. It is this very structure that enables the seamless integration of specific, human-centric environmental mandates as core, non-negotiable components of our urban habitat.

4.0 Engineering a Healthy Habitat: Integrating ‘Green Utility’ as Core Infrastructure

The new framework reframes nature not as an aesthetic luxury but as a mandatory “Biological Utility” and a “nutritional requirement” for urban health. This approach treats green infrastructure as an industrious, appreciating asset with a measurable return on investment, rather than a depreciating cost. By engineering nature directly into the urban codebase, the system delivers superior environmental outcomes and significant fiscal savings.

4.1 The 3-30-300 Rule: A Technical Mandate for Well-being

To translate the principle of “Healthy and Cultural Living” into a measurable standard, the system embeds the 3-30-300 rule as a technical mandate across all relevant zones. This rule ensures that every citizen has direct and consistent access to the restorative benefits of nature.

- 3 Visible Trees: Every resident must be able to see at least three mature trees from their home, school, or workplace. This is designed to weave nature directly into the daily visual experience of urban life, providing constant, passive mental health benefits.

- 30% Canopy Cover: Every neighbourhood must achieve and maintain a minimum of 30% tree canopy cover. This regulates the Urban Heat Island effect, filters airborne pollutants, and reduces stormwater runoff at a district-wide scale.

- 300m Walk to Green Space: Every resident must be within a 300-meter, barrier-free walk of a high-quality public green space of at least 0.5 hectares, with this distance measured via the actual pedestrian path. This ensures equitable access to recreational and restorative natural environments for all communities.

4.2 Sponge City Infrastructure: The Fiscal ROI of Nature

This “Green Utility” approach delivers a powerful financial return by replacing expensive grey infrastructure with high-performing biological systems. By moving from traditional grid layouts to circular/sponge layouts, the framework fundamentally redesigns how our cities manage water and heat.

The fiscal and environmental returns on this investment are significant:

- A reduction of up to 90% in impermeable surfaces like asphalt and concrete, allowing rainwater to be absorbed where it falls.

- Up to 50% savings on traditional infrastructure CAPEX for pipes, pumps, and treatment plants by utilizing passive stormwater management.

- A 1:3 return on investment for tree maintenance, as mature trees provide appreciating benefits that far exceed their upkeep costs.

- A 1:18 Social ROI for health, derived from the active travel infrastructure that green, walkable neighbourhoods enable.

To ensure these green assets thrive, the framework mandates “Connected Soil Volumes.” This functions as an underground lattice of shared soil and structural support, treating the root systems of urban trees as a single, connected piece of infrastructure. This critical engineering detail ensures urban trees reach their full potential and are not simply “planted in coffins” destined for a short, stunted life.

This initiative-taking integration of green utility builds resilience from the ground up. This philosophy of initiative-taking design is equally critical when addressing the unavoidable hazards of our natural environment.

5.0 Mandating Resilience: Initiative-taking Hazard Avoidance and Economic Defence

A core function of a resilient urban operating system is to shift from a culture of reactive, and often futile, mitigation to one of initiative-taking Hazard Avoidance. The new framework grounds development certainty in scientific reality, moving beyond the false security offered by depreciating grey assets like seawalls, which can and do fail. This is achieved through hard, non-negotiable limits and clear principles that protect both lives and economic productivity.

5.1 The ‘Red Line’ Policy: A Hard Limit on Risk

The framework introduces a “Red Line” policy that prohibits development in areas of unacceptable risk. This is not a matter for negotiation or consent-level debate; it is a hard limit based on a mandatory risk matrix. Development is strictly avoided in the “Top-Left Risk Quadrant”—areas where there is a High Likelihood of an event with Catastrophic Consequences.

This policy is supported by two critical requirements:

- A 100-Year Climate Horizon: All planning and infrastructure decisions must be based on a climate-change baseline projected to the year 2126, ensuring long-term resilience is built in, not bolted on as an afterthought.

- “Residual Risk” Modelling: The system mandates “intellectual honesty” by forcing planners to model for the “failure of existing defences.” This requires planning for a 500-year flood event breaching a 100-year flood wall, ensuring development certainty is grounded in scientific reality, not the false security of depreciating grey assets.

5.2 The Newcomer Principle: An ‘Invisible Shield’ for Economic Engines

Resilience is not only environmental but also economic. The system uses the Newcomer Principle, also known by its legal framing “First in Time, First in Right,” to manage reverse sensitivity and protect Aotearoa’s critical economic engines—such as ports, rail hubs, and 24/7 industrial facilities. The principle reallocates the responsibility and cost of mitigation to the party introducing change into an environment.

For example, if a developer builds a new residential apartment block next to an existing 24/7 port, that developer—the “newcomer”—is required to pay for mitigation measures like high-grade acoustic glazing and mechanical ventilation for the new homes. This creates an “invisible shield” around the port. It ensures our vital economic infrastructure is not slowly “litigated out of existence” by noise complaints from new residents, allowing the city’s economic heart to function without impediment.

By establishing these hard limits and clear rules of engagement, the framework creates a more predictable, insurable, and resilient urban system for generations to come.

6.0 Conclusion: The Strategic Imperative for a Resilient Habitat

The Aotearoa Planning Bill 2025 is more than a legislative reform; it is a fundamental “system upgrade” designed to build a resilient and prosperous nation for the next century. By importing the disciplined DNA of Japanese land-use law and adapting it to our unique context, we are liquidating the “regulatory debt” of the past and installing an initiative-taking, performance-based urban operating system. This new blueprint, actively being implemented and evaluated in initiatives like the Manukau Beta Test, replaces bureaucratic friction with legal certainty, speculative chaos with infrastructure-led growth, and environmental afterthoughts with integrated green utility.

The entire framework can be understood as a clear, strategic formula for national success, summarized by the Resilient Habitat Equation:

Science (3-30-300) + Tool (The Funnel) + Limit (Hazard Avoidance) = The Resilient Habitat

For decision-makers and the development industry, the adoption of this new blueprint delivers a compelling “Triple ROI”, providing the certainty and stability required for long-term investment and sustainable growth. This is the ultimate strategic imperative for its implementation.

- Legal Certainty: Delivered via the “Funnel” model of upstream decision-making, which is enforced by the “Golden Rule” and “Section 12 Legal Teeth.” These mechanisms ensure high-level decisions cannot be relitigated, eliminating the risk and cost of project-level litigation and providing a clear path for compliant development.

- Economic Scale: Enabled by a universal codebase of National Standardised Zones. This consistency allows the construction and finance industries to develop national-scale pipelines, “off-the-shelf” designs, and efficient supply chains, driving down costs and accelerating delivery.

- Long-term Resilience: Guaranteed through the mandatory integration of “Green Utility” as an appreciating infrastructure asset and the hard, science-based limits of the “Red Line” policy. This ensures our communities are not only prosperous but also safe, healthy, and durable.