What is Public Welfare Supreme and why is it the cornerstone of my submission

My submission which I will be sharing into the blog as a series will make mention of Public Welfare Supreme as a core tenant of an amended Planning Bill. This post looks at the basics of Public Welfare Supreme to bring you up to speed before immersing ourselves with my submission later on.

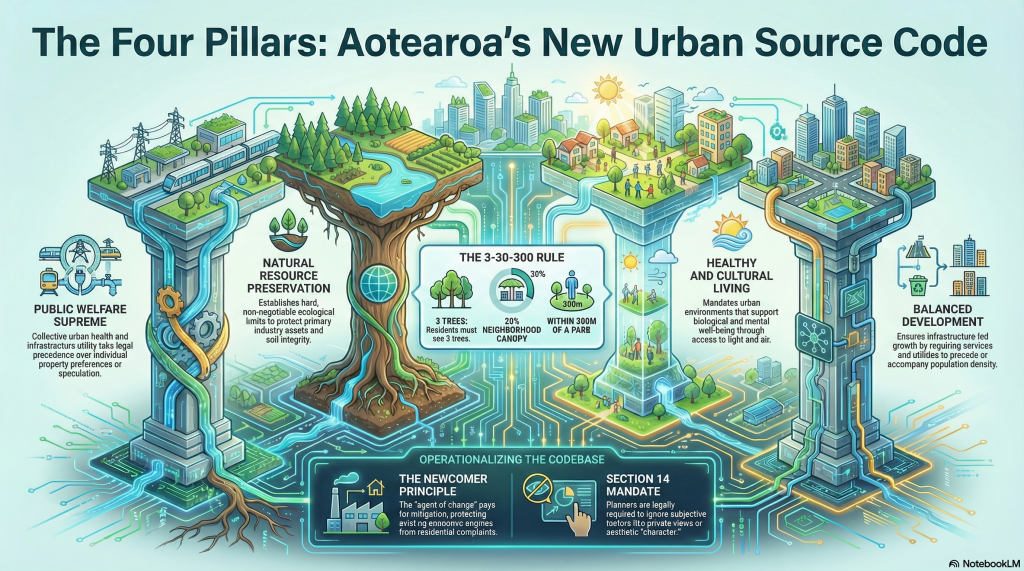

The “Four Pillars of Public Welfare” function as the ethical and legal “Source Code” of my Aotearoa Planning Bill 2025 submission. Adopted directly from Japan’s 1974 Land-Use Law, these principles are designed to solve the “crisis of chaos” (speculation and sprawl) by legally prioritizing collective needs over individual property rights.

Why? From the opening remarks of my main submission: The basic premise of my submission is doing what Minister Bishop has stated more than once, to emulate the Japanese planning system particularly for the Standardised Zones (the NZ version yet to be drafted by the Ministry for the Environment).

However, for Bishop to emulate the Japan system especially around the Standardised Zones, you need to understand the two key pieces of legislation that set those zones: the Japan Land Use Law Act 1974, and the Building Standards Act 2011 (sets urban design and building controls (a superior version to our obsolete Building Act 2004). I won’t comment nor draw on comparisons to the Building Standards Act but the Japan Land Use Law Act is the main inspiration for my submission. Public Welfare Supreme is the core tenant of the Japan Land Use Law Act 1974.

The four specific pillars of the Public Welfare Supreme practice

Strategic Outcome: The ultimate goal of this model is to replace a subjective “Culture of Permission” with an objective “Culture of Adherence.”

1. Public Welfare (The Prime Directive)

This is the overarching principle that establishes the hierarchy of rights.

- Definition: It establishes that the collective health, safety, and functionality of the city take legal precedence over individual property preferences and speculative interests

- Operational Impact: Private development cannot occur at the expense of community safety or infrastructure capacity. This is legally enforced via the Section 14 Mandate, which instructs planners to ignore subjective individual complaints—such as the loss of private views or “neighbourhood character”—in favour of objective collective benefits like housing capacity and transit utility.

2. Natural Resource Preservation

This pillar shifts environmental protection from a “nice-to-have” to a hard constraint.

- Definition: It mandates the establishment of non-negotiable ecological limits to ensure the long-term stewardship of land, soil, and natural assets.

- Operational Impact: Planning must precede development to prevent the destruction of “Economic Engines” like fertile soil. This pillar justifies the “Urban Dam” (Urbanisation Control Area), which strictly prohibits housing on productive rural land to prevent irreversible fragmentation.

3. Healthy and Cultural Living Environments

This pillar treats the quality of the human habitat as a statutory right rather than a luxury.

- Definition: It mandates the creation of urban environments that actively support the mental and physical well-being of residents.

- Operational Impact: Grounded in Attention Restoration Theory (ART), this pillar requires legal protection for access to sunlight, fresh air, and nature. It is physically operationalized through the 3-30-300 Rule (3 trees visible, 30% canopy cover, 300m to a park), ensuring that densification does not lead to psychological or environmental decay.

4. Balanced Development

This pillar ensures growth is efficient and equitable rather than chaotic.

- Definition: It requires that urban growth be systematic, orderly, and synchronized with infrastructure capacity

- Operational Impact: This institutionalizes the mantra of “Pipes before People.” Development rights are legally tethered to the existence of infrastructure (the “Density Follows Frequency” rule). This prevents the creation of “unserviced fringes”—sprawling neighbourhoods built without the necessary sewage, roads, or transit to support them.