Looking Backwards to Propel Forwards in our Planning Future

This blog post provides a high level wrap up of what would happen if Public Welfare Supreme was adopted into the Purpose and Goals of the Planning Bill.

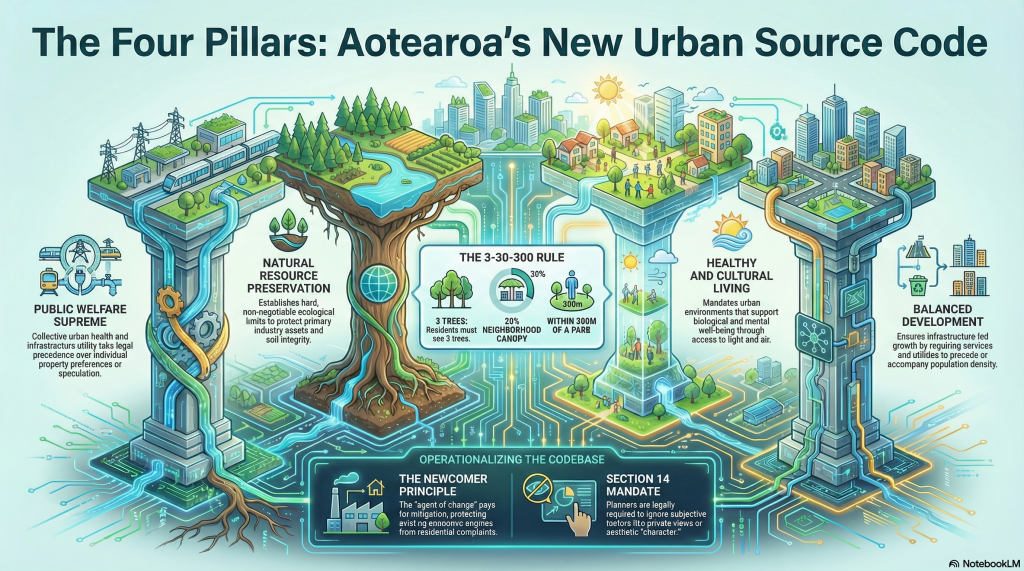

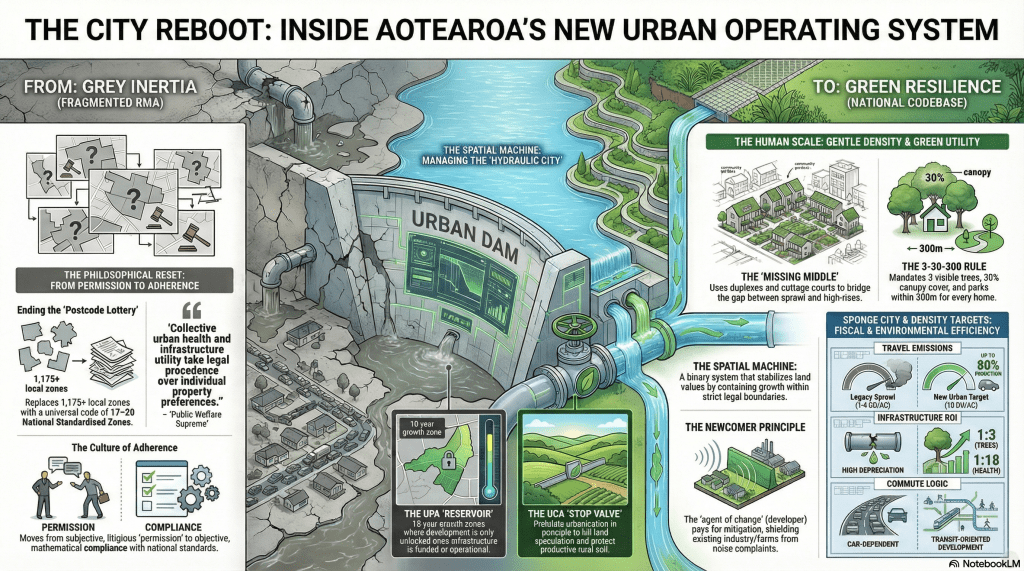

Modern urban life is currently strangling itself within a “trinity of misery”: skyrocketing housing costs that outpace wages, soul-crushing traffic congestion, and a parasitic urban sprawl that consumes New Zealand’s productive soil like a slow-moving virus. For decades, Western planning has attempted to solve these issues through reactive, “feelings-based” regulations—a state of “Gray Inertia” where every window frame and fence colour is litigated into stagnation.

In a radical strategic pivot, the Aotearoa Planning Bill looks back to 1974 Japan to find the source code for our future. To understand this shift, we must stop viewing the city as a static map of property lines and start seeing it as a machine—specifically, a hydraulic one.

1. The Physics of the “Hydraulic City”

The core premise of the new Planning Act is that a city functions according to the laws of fluid dynamics. In this metaphor, the city centre is a pressurized vessel. As a city achieves economic success, wealth and rising land values act as a “piston,” pushing down with immense force on the vessel’s contents.

The “fluid” represents the people who power the city—the working class, service providers, and families. In a poorly planned system, this pressure creates a “leak.” When the core becomes unaffordable, the fluid is forced into the path of least resistance: the unserviced urban fringes. This is not merely an aesthetic problem; it is a “measurable economic haemorrhage” of negative productivity. Sprawl mandates a reliance on private vehicles that drains household capital and creates poverty traps, forcing those who can least afford it into two-hour commutes. Success, quite literally, destroys the city’s functionality without a proper “urban dam.”

2. The System Architecture: “The Funnel”

The Aotearoa Planning Act replaces “Grey Inertia” with a hierarchical “Funnel” architecture. This is a move from a culture of permission (where you beg for consent) to a culture of adherence (where you follow the code).

The Funnel operates on a “No Relitigation” rule: decisions made “upstream” at the National level cannot be fought “downstream” at the Consenting stage.

- National Goals: Central Government defines the outcomes (Housing, Infrastructure, Protection).

- National Instruments: Mandatory National Standards for zones and rules.

- Regional Combined Plans: Consolidation of 100+ District Plans into 15 Regional Strategies.

- Consents: Execution with a narrowed scope of effects.

By front-loading community engagement to the plan-making stage, the bill stops local councils from rebelling through “procedural penalties” (Section 12), forcing alignment with national consistency.

3. Building the “Urban Dam” (UPA vs. UCA)

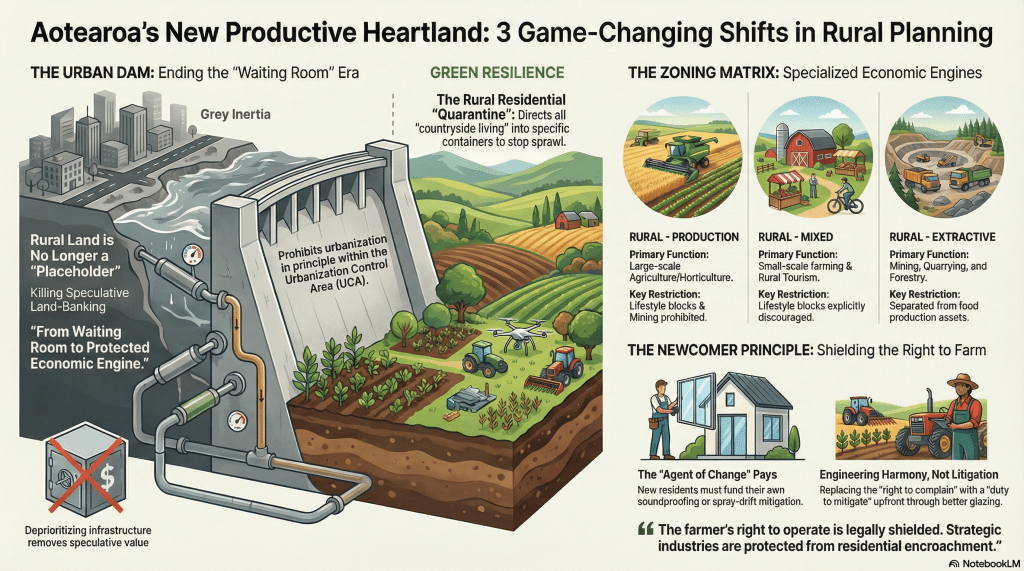

To contain the hydraulic pressure of growth, the landscape is divided into two rigid zones: the Urbanization Promoting Area (UPA) and the Urbanization Control Area (UCA).

- The Reservoir (UPA): Land designated for systematic urbanization within a 10-year horizon. Here, infrastructure is the lead indicator. Roads, sewers, and transit are built before density is unlocked. The tank is built before the fluid is pumped in.

- The Dam Wall (UCA): Urbanization is prohibited in principle. The state “weaponizes inconvenience” by explicitly withholding infrastructure. By signalling that “the pipes are never coming,” the government kills speculative land banking. Rural land value then reflects its utility (farming) rather than its speculative potential (subdivision).

To create the rational grid required for the reservoir, the bill utilizes Land Readjustment. Rather than using eminent domain, the state pools fragmented plots, draws a perfect grid with streets and parks, and returns smaller but “fully serviced” plots to owners. A farmer trading 10 acres of unserviced scrub for 7 acres of high-value urban land realizes a massive financial win while the city gains functional infrastructure at zero land-acquisition cost.

4. Section 14: Breaking the “Nitpicking Trap”

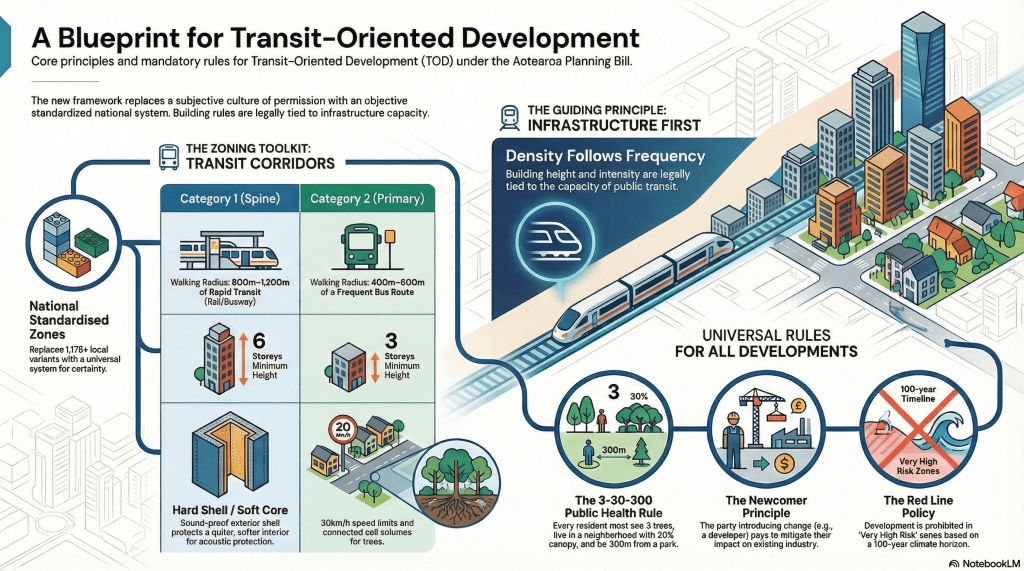

The greatest friction in modern development is the “nitpicking trap,” where subjective objections paralyze growth. Section 14 of the Bill introduces “The Ignore List”—a legal mandate requiring planners to disregard the four primary weapons of the “Not in My Backyard” (NIMBY) movement:

- Private Views: Impacts on views from private property are no longer a legal ground for objection.

- Aesthetic Character: Subjective “visual character” or “vibe” is disregarded in favour of objective standards.

- Social Status: The perceived “class” or status of future residents is irrelevant to the planning process.

- Trade Competition: Existing businesses cannot use the planning system to block new competitors.

5. Density Follows Frequency: The Math of Proximity

The Act treats urban density as a mathematical problem of service populations. It replaces height maximums with mandatory height minimums. It is considered “fiscally irresponsible” to build low-density housing near billion-dollar rail investments.

A neighbourhood must reach 15 Dwelling Units per Acre (DU/AC) to remain commercially viable; below this threshold, local shops fail and infrastructure maintenance costs become a fiscal liability.

| Feature | Category 1 (Spine Corridor) | Category 2 (Primary Corridor) |

| Transit Type | Rapid Transit (Rail / Busway) | Frequent Bus Services |

| Mandatory Min. Height | 6 Stories | 3 Stories |

| Intensification Zone | 400m – 600m from road reserve | 400m – 600m walkable catchment |

| Speed Limit | 30 km/h | 30 km/h |

6. The Newcomer Principle: Engineering over Litigation

“Reverse Sensitivity” occurs when new residents move next to established industries (ports, factories) and then sue to shut them down. The “Newcomer Principle” dictates that the party introducing the change bears 100% of the cost for mitigation.

To build near a transit spine or industrial hub, a developer must install high-grade acoustic glazing and mechanical ventilation. This engineering-first approach soundproofs neighbour wars before they start and removes the legal right to complain. The city’s economic engines are protected by a “Hard Shell” frontage, shielding a “Soft Core” of residential quietude behind.

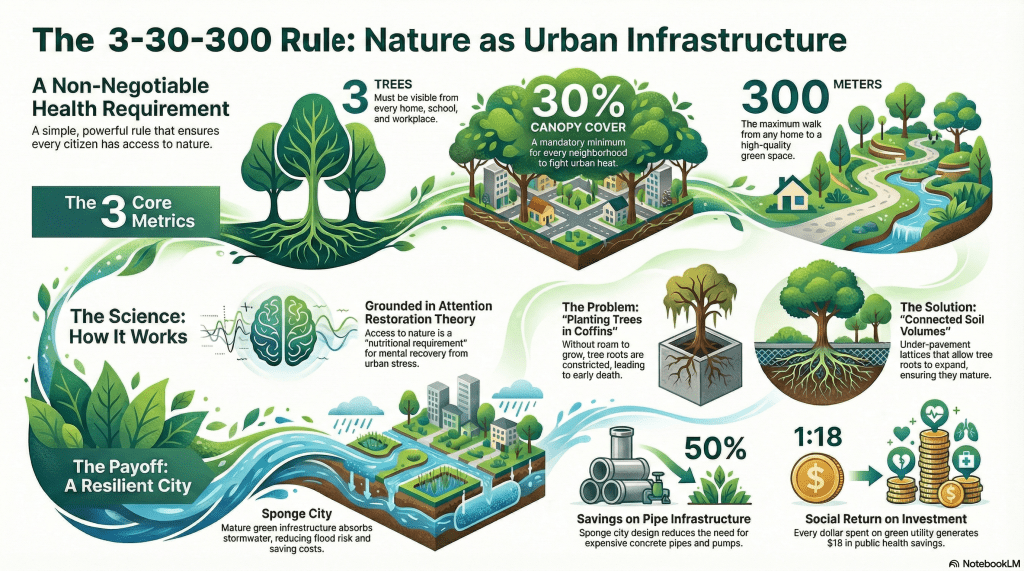

7. Green Utility: Nature as a Public Health Requirement

Nature is no longer an aesthetic luxury; it is a “biological utility.” Based on Attention Restoration Theory, the Act mandates the 3-30-300 Rule to mitigate urban stress and the heat island effect:

- 3 Trees: Every building must see at least three mature trees.

- 30% Canopy: Every neighbourhood must achieve 30% coverage.

- 300 Meters: Every resident must be within 300 meters of quality green space.

To avoid “trees in coffins,” the Act mandates “Connected Soil Volumes”—underground trenches that act as an “internet for roots,” allowing trees to thrive and function as a “Sponge City” that absorbs stormwater, liquidating the need for expensive grey infrastructure.

8. Rural Stewardship: Protecting the Economic Engine

Unlike Japan, Aotearoa’s economy is built on soil. The Act introduces a new framework for Rural Stewardship to protect the “Engine of the Soil” from fragmentation:

- Rural – Production: Dedicated to large-scale agriculture. Extractive industries (mining/quarrying) are banned to protect soil quality.

- Rural – Mixed: Enables small-scale farming and tourism. Lifestyle blocks are explicitly discouraged.

- Rural – Extractive: Segregates heavy industry (mining, forestry) from food production.

- Rural Residential: A contained zone for “lifestyle” demand, capped at 500 sq.m buildings to divert residential friction away from productive land.

9. Digital Sandboxes and Zero-Overhead Incubators

The Act aims to end the “Dormitory Model”—housing as mere storage—by permitting “corner-site” micro-businesses as-of-right. This creates “Zero-Overhead Incubators,” where live-work units act as a hedging strategy against commercial market volatility. By consolidating a workspace and residence into one cost, entrepreneurs can “fail fast” or scale without predatory leases.

To de-risk these radical shifts, the Bill utilizes “Digital Sandboxes.” These simulations treat the city as a living organism, allowing planners to model emergent dynamics—such as the 33% reduction in Vehicle Miles Travelled (VMT) or the impact of low-rent housing mandates—before physical implementation.

Conclusion: Are You Ready for the Machine?

The Aotearoa Planning Act represents a move from a “feelings-based” system of stagnation to a mathematical system of “Green Resilience.” The trade-off is stark: to gain a vibrant, walkable, and functional city, we must give up the “quarter-acre dream” and the illusion of total control over our neighbour’s property.

Would you rather have a veto over the height of the building next door, or live in a city where the infrastructure is actually designed to support human life?

Urban Reboot?

Rural Reboot?