A Briefing on using a Public Welfare based Planning Act that still better enables the Private Sector

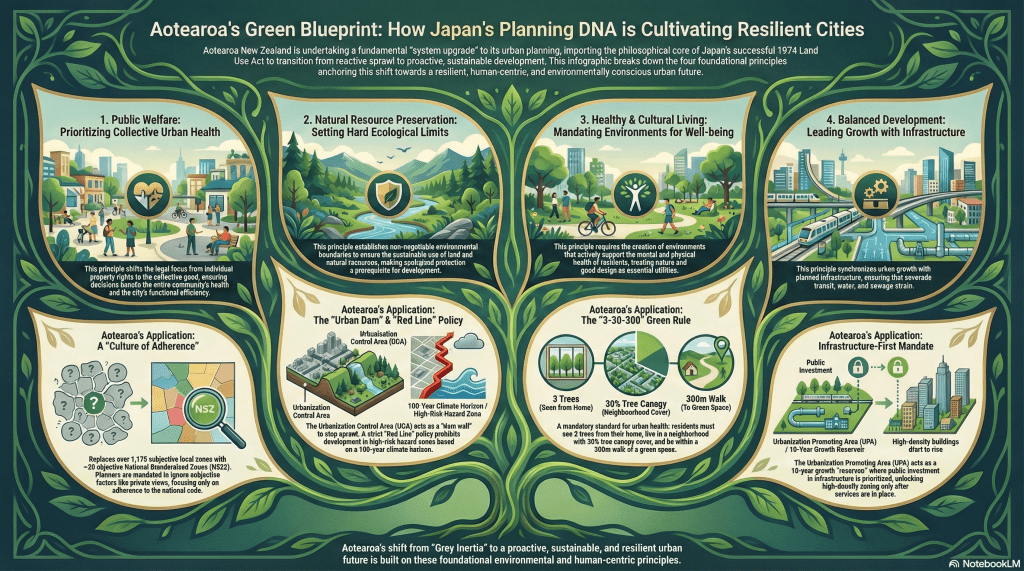

Context as per my opening remarks in my main submission: The basic premise of my submission is doing what Minister Bishop has stated more than once, to emulate the Japanese planning system particularly for the Standardised Zones (the NZ version yet to be drafted by the Ministry for the Environment). However, for Bishop to emulate the Japan system especially around the Standardised Zones, you need to understand the two key pieces of legislation that set those zones: the Japan Land Use Law Act 1974, and the Building Standards Act 2011 (sets urban design and building controls (a superior version to our obsolete Building Act 2004). I won’t comment nor draw on comparisons to the Building Standards Act but the Japan Land Use Law Act is the main inspiration for my submission.

Again, as you will notice through my comprehensive submission the main tenants of the Planning Bill, and even the NPS UD (including to be drafted Standardised Zones), Infrastructure, and Natural Hazards are generally supported. What I am doing in bringing in Japanese wisdom to strengthen the Bill to produce outcomes the Minister is trying to emulate. This includes better urbanism and a protected but functioning rural sector.

The submission fuses a mix of storytelling, comparisons, and desired outcomes to form the who, what, where, when, why, and how around the technical aspects document and the Bill. Thus, it can appear aspects of the submission are repeating itself when they are actually covering another but complementary section of the Planning Bill.

PLEASE NOTE: for sake of clarity and avoiding confusion any mention of Aotearoa Planning Bill (2025) (simply The Bill) is pertaining to the AMENDED version of the Planning Bill if all points of my submission are carried.

The (amended) version of the Aotearoa Bill 2025 follows the Public Welfare Supreme practice at all times.

Executive Summary

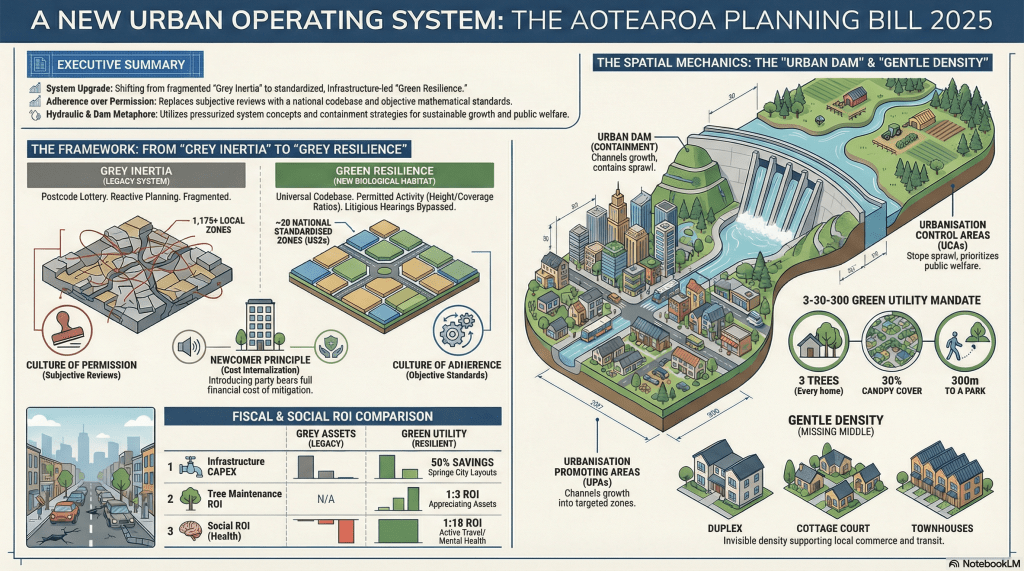

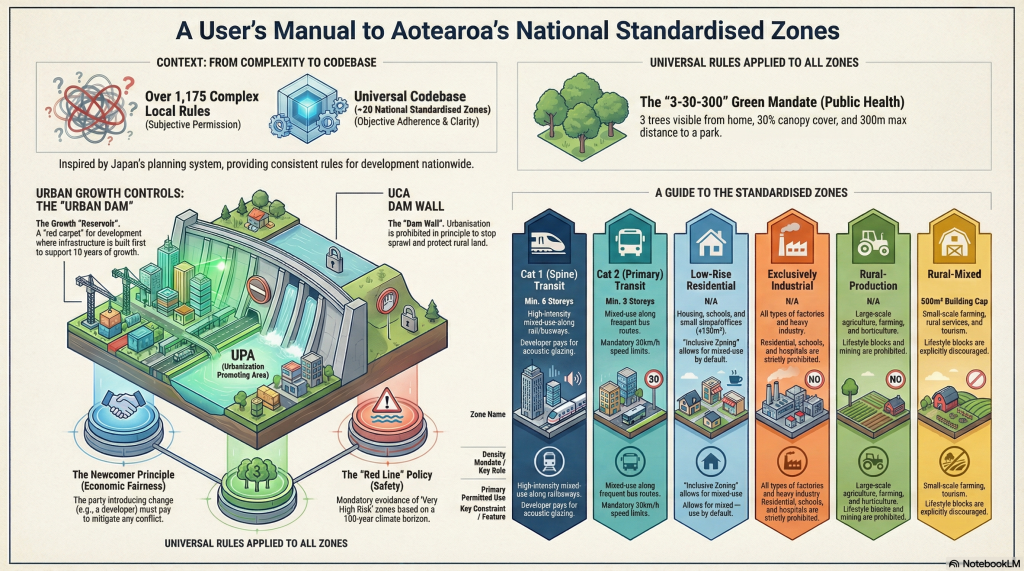

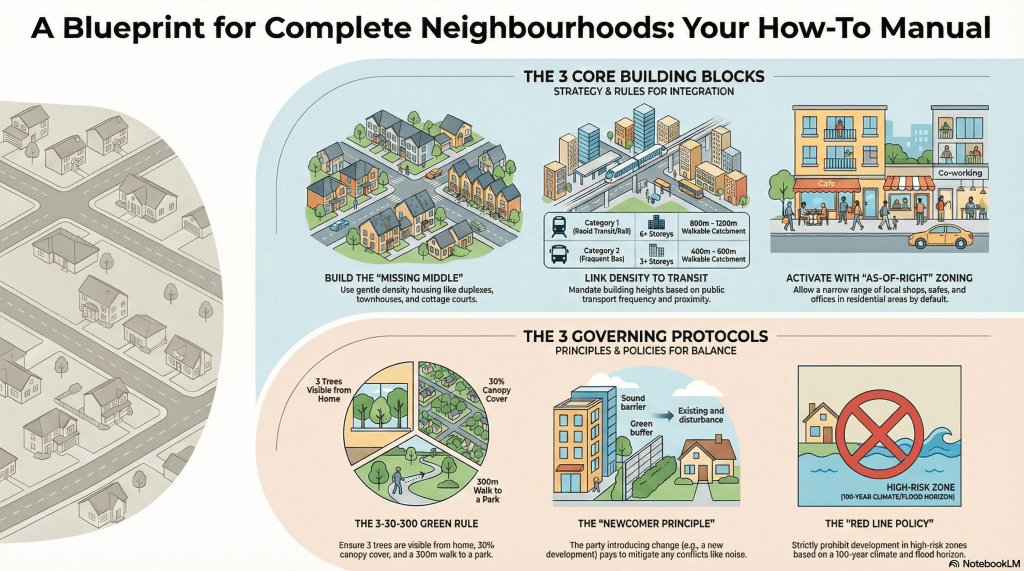

The Aotearoa Planning Bill 2025 represents a fundamental paradigm shift in land-use regulation, moving from the reactive, “effects-based” management of the Resource Management Act (RMA) to an “outcomes-focused” national system. Drawing heavily from the Japanese Land-use Law of 1974, the Bill aims to solve the “trinity of misery”—astronomical housing costs, chronic traffic congestion, and chaotic urban sprawl—by implementing a standardized, “as-of-right” planning framework.

Central to this proposal is the “Hydraulic City” metaphor, which views urban growth as a pressure system requiring a containment structure known as the “Urban Dam.” By dividing land into Urbanization Promoting Areas (UPA) and Urbanization Control Areas (UCA), the Bill seeks to synchronize infrastructure investment with density, protect productive rural soil, and ensure long-term climate resilience through mandatory hazard avoidance.

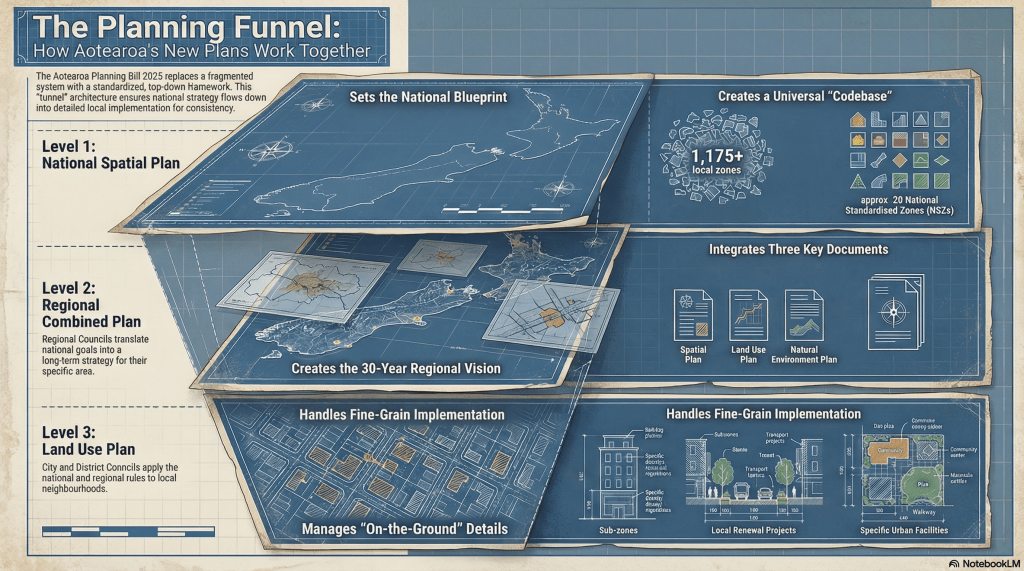

1. System Architecture: The “Funnel” of Authority

The Bill replaces over 100 disconnected district plans with approximately 15–16 Regional Combined Plans. This is structured as a hierarchical “Funnel” to ensure consistency and prevent the relitigation of high-level policy at the local level.

| Level | Authority | Primary Function |

| 1. National | Central Government | Sets National Goals (Outcomes) and National Instruments (Policy Direction/Standards). |

| 2. Regional | Regional Councils | Drafts Regional Spatial Plans (30-year vision) and administers Base Zones. |

| 3. Local | District Councils | Implements sub-zones, “Urban/Rural Development” areas, and Promotion Area Zones. |

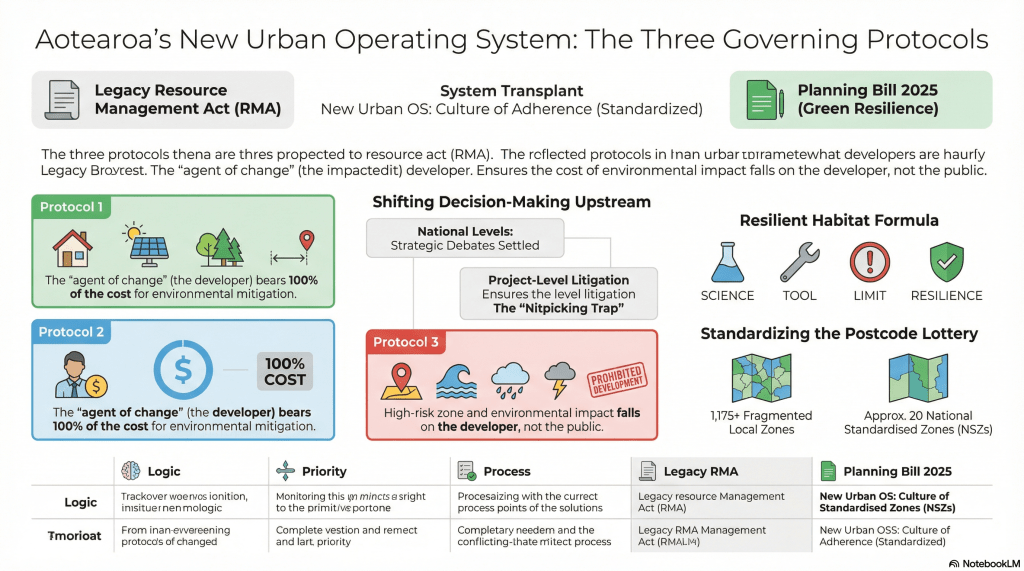

Core Principle (No Relitigation): Decisions made “upstream” at the National level (e.g., a National Standard for housing density) are binding and cannot be challenged “downstream” during local consent hearings.

2. Philosophical Foundations

The Bill adopts four foundational principles derived from the Japanese model to replace the current “culture of permission” with a “culture of adherence”:

- Public Welfare: Collective urban health and functioning rank above individual property preferences.

- Natural Resource Preservation: Planning must protect resources rather than treating growth as an excuse to pave over them.

- Healthy and Cultural Living: Built environments must support mental and physical well-being.

- Balanced Development: Growth must be coordinated and led by infrastructure.

3. The Hydraulic City and the Urban Dam

The Bill conceptualizes the city as a hydraulic machine. As a city succeeds, the “piston” of rising wealth and land value creates pressure. Without containment, the “fluid” (the working class and service workers) is forced out to unserviced fringes, resulting in sprawl.

The Urban Dam Mechanism

- Urbanization Promoting Area (UPA): Acting as a “reservoir,” this land is designated for systematic urbanization within a 10-year horizon. Infrastructure (streets, sewage, transit) is legally prioritized and must be implemented first to unlock density.

- Urbanization Control Area (UCA): Acting as a “stop valve,” urbanization here is prohibited in principle. Infrastructure is explicitly deprioritized to kill speculative land-banking. Rural land value in the UCA reflects its utility (farming) rather than its potential (subdivision).

4. National Standardised Zones (NSZs)

To eliminate the “postcode lottery” of 1,175+ fragmented local rules, the Bill establishes a limited set of National Standardised Zones. These are “soft” and inclusive, assuming mixed-use is beneficial by default.

Key Urban Zone Examples

- Category 1 (Spine Corridor): Located along rapid transit. Mandates a minimum height of six storeys.

- Category 2 (Primary Corridor): Located along frequent bus routes. Mandates a minimum of three storeys.

- Mixed-Use Residential: Permits small shops, offices, and even “karaoke boxes” (up to 3,000 sq.m) within residential areas to create self-contained villages.

Eliminating the “Nitpicking Trap” (Section 14)

The Bill creates a legal “Ignore List” of subjective factors that planners and neighbours cannot use to block development:

- Impacts on private views from private property.

- Aesthetic character (unless in a designated natural landscape).

- Social status or project viability of future residents.

- Trade competition (blocking a competitor’s business).

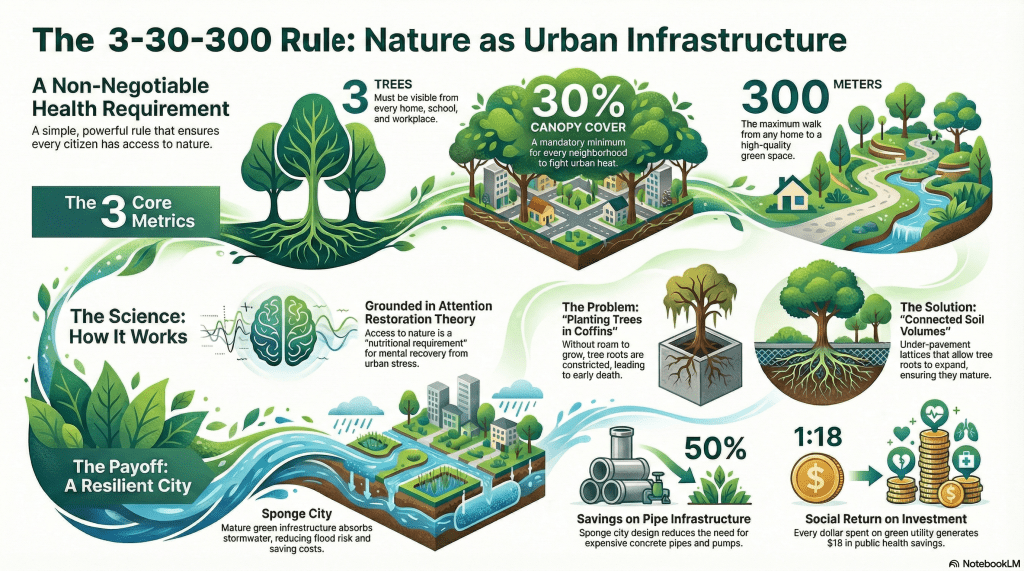

5. Environmental Stewardship and “Green Utility”

The Bill transitions nature from an aesthetic luxury to a “biological utility” via the 3-30-300 Rule:

- 3 Trees: Every home, school, and workplace must be able to see at least three trees.

- 30% Canopy: Every neighbourhood must maintain 30% canopy cover to mitigate the heat island effect.

- 300 Meters: Every resident must be within 300 meters of high-quality green space.

Resilience and Safety

- Red Line Policy: A mandatory avoidance rule based on a 100-year climate horizon. Development is strictly prohibited in “Very High Risk” zones (floodplains, landslide-prone areas).

- Sponge City Technology: Mandates connected soil volumes and permeable surfaces to allow the city to absorb water naturally, reducing “grey asset” (pipe) costs by up to 90%.

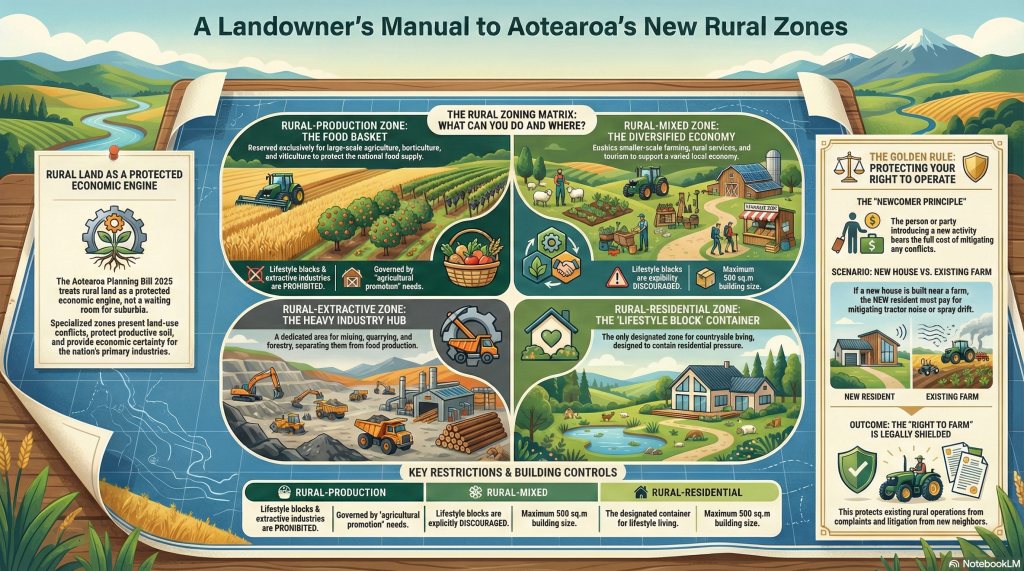

6. Rural Stewardship and the “Newcomer Principle”

To protect the agricultural “Economic Engine,” the Bill organizes the countryside into three primary zones:

- Rural – Production: Dedicated to large-scale agriculture, horticulture, and viticulture. Extractive industries and residential uses are prohibited.

- Rural – Mixed: Enables small-scale farming and rural tourism.

- Rural – Extractive: Dedicated to mining, quarrying, and forestry, segregating heavy industry from food production.

The Lifestyle Block Restriction

The Bill explicitly discourages the “lifestyle block” dream. These are viewed as “parasitic on infrastructure,” fragmenting productive land while demanding expensive municipal services. “Countryside living” is instead contained within small Rural Residential zones with strict building caps.

The Newcomer Principle

To solve reverse sensitivity (e.g., new residents complaining about noise from an established port), the Bill mandates:

- The party introducing change (the newcomer/developer) bears all costs of mitigation.

- New buildings near industrial zones must include high-grade acoustic glazing and mechanical ventilation.

- Residents lose the right to sue established economic engines for noise or smell if mitigation standards were met.

7. Economic Impact: From “Dormitory” to “Ecosystem”

The Bill argues that the “Dormitory Model” (housing-only suburbs) creates “negative productivity” through lost travel time and infrastructure debt.

Zero-Overhead Incubators

The Bill promotes live-work units to lower entry barriers for micro-entrepreneurship. These act as “Zero-Overhead Incubators,” allowing residents to run businesses (studios, salons, professional services) without separate commercial leases.

The Density Tipping Points

Planning must meet specific mathematical thresholds to ensure commercial viability:

- 1–4 DU/AC: Retail wasteland; car dependency.

- 8 DU/AC: Functional walkable community (baseline for cohesion).

- 15+ DU/AC: The economic engine; minimum for grocery store and transit viability.

- 24+ DU/AC: The “Goldilocks Zone” of urban efficiency.

“The system is designed to stop relitigation. The most effective way to influence land use regulation is no longer at the consent hearing, but at the plan-making table.” — Source Context Conclusion

Summary of my submission to the Planning Bill: Going from Grey to Green!