Prelude to the Planning Reforms

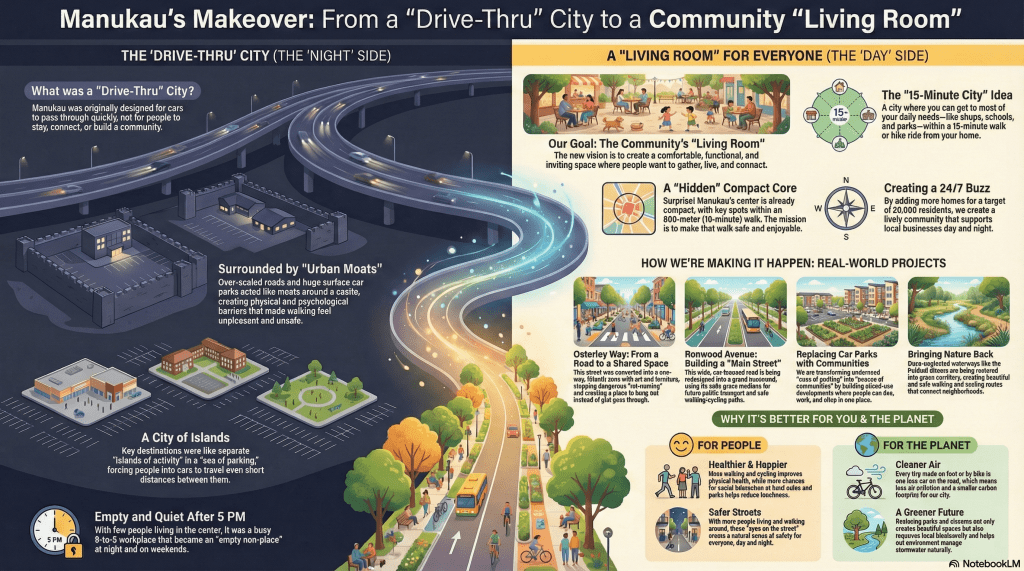

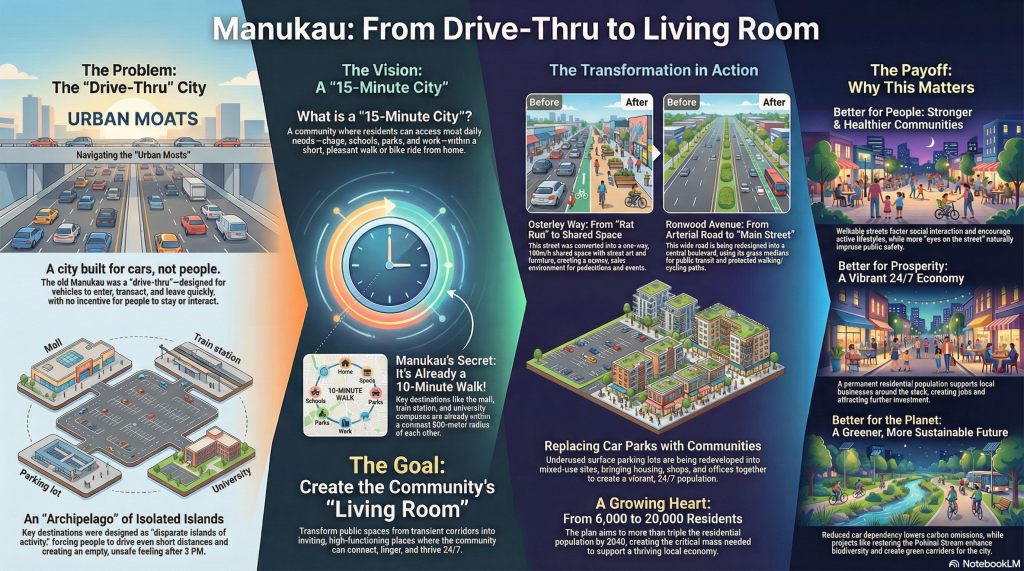

We have covered how road design can harm other road users. We have also covered how reclaim streets, turn myopic urban areas into urban super blocks, what to do with all that parking, and even mentioned how to self-fund urban renewal and transit lines using Tokyo as the inspiration and Manukau City Centre as the example.

However, behind the scenes the policy framework has been lurking in the background that would enable most of this to happen. In Aotearoa this is our Planning Reforms, which Part 9.5 preludes into before Part 10 and the final part of the ‘Ben Does Planning Series’ acts as the hand off to those reforms being explored in depth.

The Policy Framework for the 24-Hour Human City

1. The Urban Duality: Understanding the Day and Night Rhythms

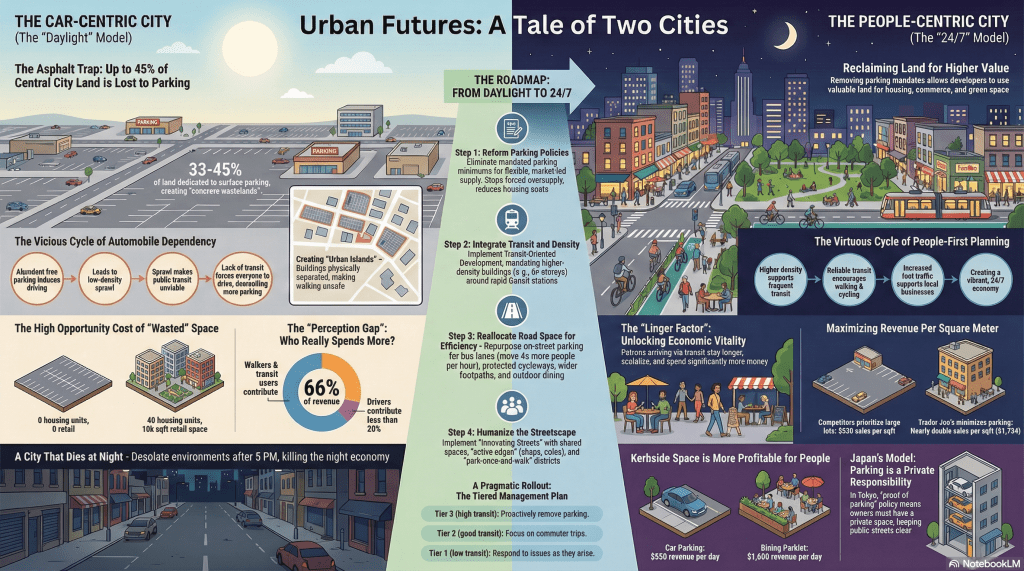

A city’s pulse is its primary economic indicator; if the rhythm is interrupted by static storage, the asset depreciates. Urban planning is the management of a biological rhythm, where a successful metropolis must breathe differently across a 24-hour cycle—prioritizing utility during the day and vibrancy at night. For the modern decision-maker, the strategic dilemma is no longer about traffic flow, but about land-use efficiency: the choice between dedicating finite urban land to “private metal box storage” or to “human movement and interaction.”

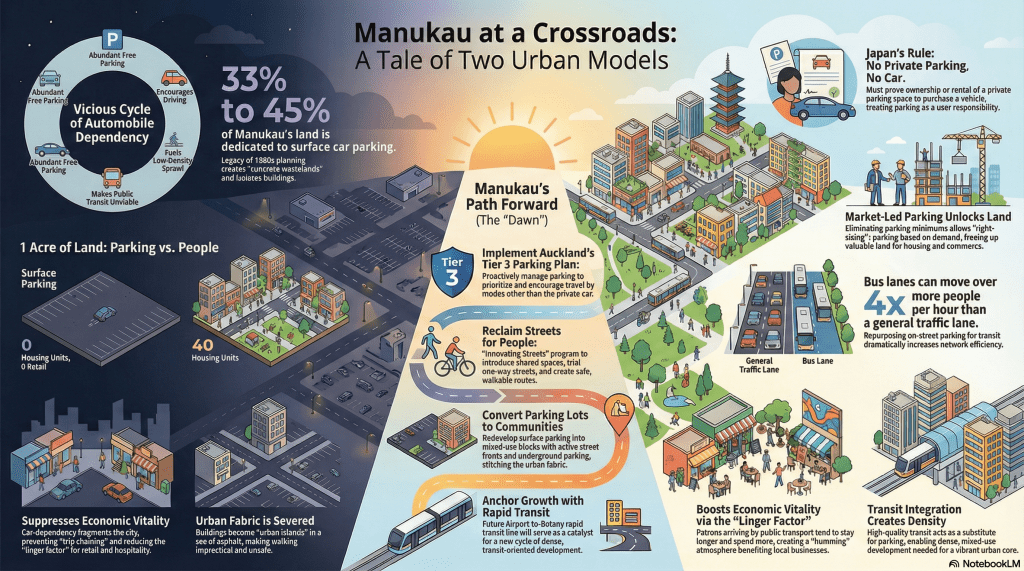

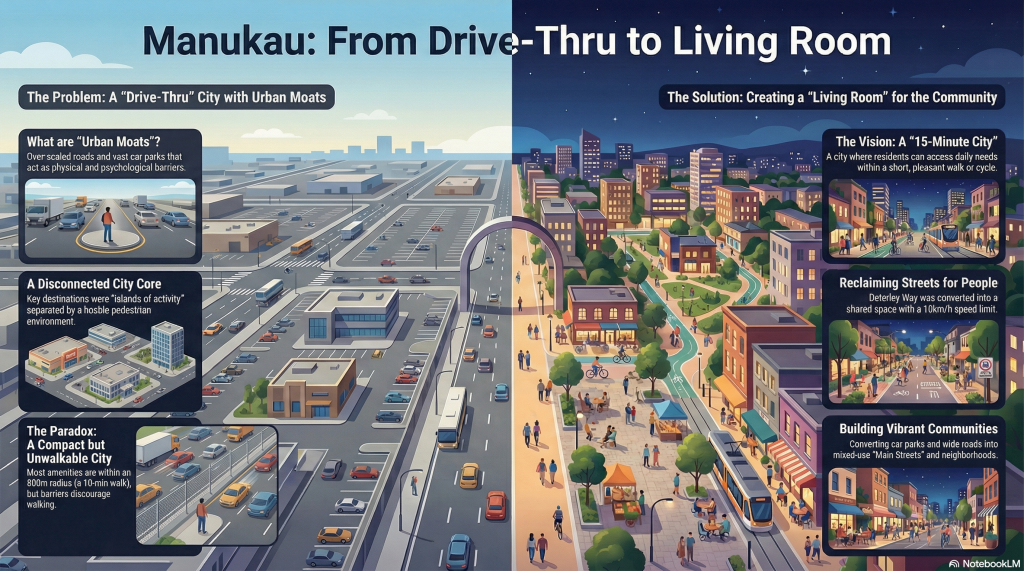

This policy framework evaluates this conflict through two high-contrast lenses: the “Concrete Wasteland” of Manukau, Auckland—a 1960s legacy of car-centric sprawl—and the “Market-Led Density” of Tokyo, Japan. To transition from a stagnant storage yard to a high-value habitat, we must move beyond the “Decision Maker’s Dilemma” and address the hard data of current fiscal and social inefficiencies.

2. The Daylight Audit: Analysing the “Concrete Wasteland” Inefficiency

Daytime land-use efficiency is the baseline for urban productivity. When land is allocated to its most productive use, it generates compounded value through residential density, retail turnover, and employment. In Manukau, however, legacy planning has resulted in a staggering over-allocation of surface parking that far exceeds global car-dependent norms:

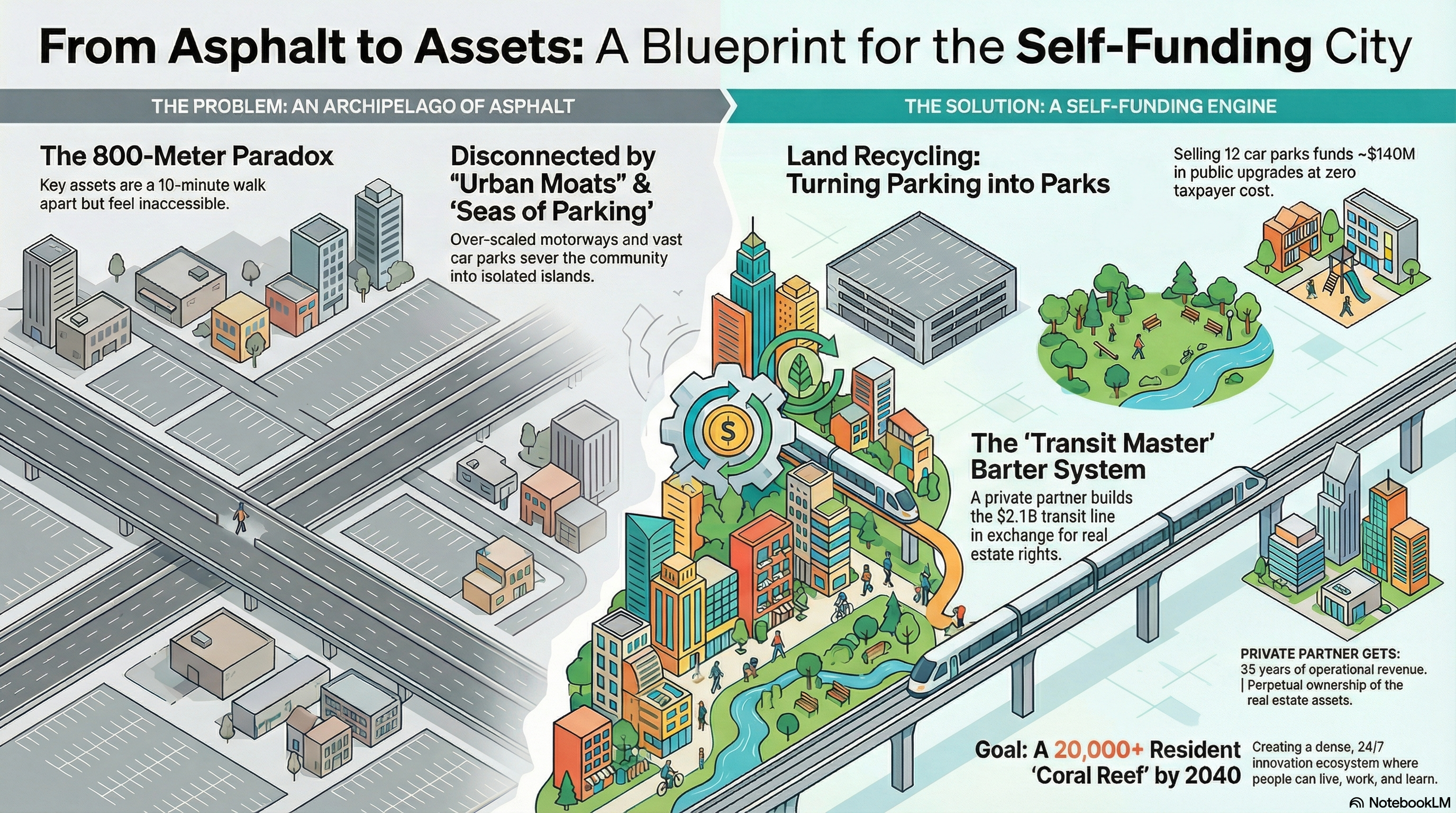

- Manukau Surface Parking Allocation: 33% to 45% of total land area.

- Typical Car-Dependent City Average: ~25%.

- Asset Inefficiency: Manukau utilizes nearly double the space for vehicle storage compared to cities already struggling with car dependency.

This over-allocation creates the Walkability Paradox. Geographically close destinations—often less than two hundred meters apart—are physically and psychologically severed by “Urban Islands.” Crossing these vast, windswept expanses of hot tarmac is so hostile to the human experience that residents are forced into cars for even the shortest trips. This absurdity is the direct result of a design that prioritizes stationary machines overactive inhabitants.

The Vicious Cycle of Car Dependency Ample Parking → Induced Driving → Urban Sprawl → Unviable Transit → Demand for More Parking

Strategically, this “asphalt trap” ensures that half of the city centre remains an economic void during its most productive hours, trapping the region in a cycle of heat, desolation, and depreciating value.

3. The Economic Shadow: Evaluating the Opportunity Cost of Parking

The fiscal reality is that surface parking represents the lowest-value use of prime real estate. The “Opportunity Cost”—what we lose by not developing that land—is the single most important metric for a Lead Strategist.

Yields per Acre: Surface Parking vs. Walkable Mixed-Use

| Metric | Surface Parking | Walkable Mixed-Use |

| Housing Units | 0 | ~40 Units |

| Retail Space | None | High (Active Frontages) |

| Employment Density | Near Zero | High (Office/Commercial) |

| Revenue Generation | Low (Minimal Parking Fees) | High (Sales, Leases, Tax Base) |

The market-led Trader Joe’s Model provides the “smoking gun” for land-use efficiency. By “right-sizing” parking and prioritizing retail density, Trader Joe generates approximately 1,734 per square foot**—nearly double the **930 per square foot produced by Big Box competitors who prioritize sprawling, low-velocity parking facilities. High turnover, not storage, drives sales.

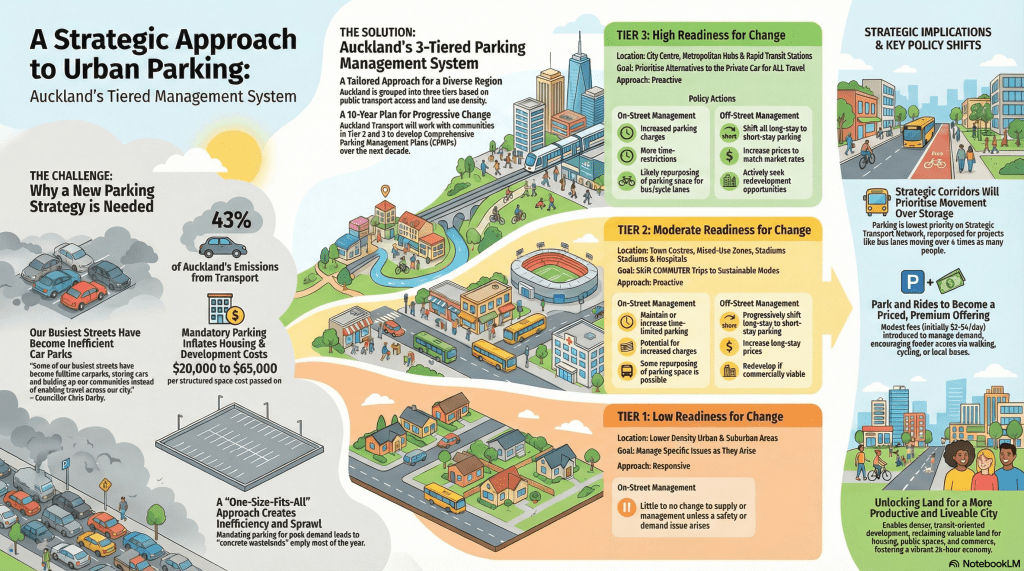

Furthermore, the Hidden Subsidy of parking construction represents a massive barrier to developer viability. Structured parking costs between $37,000 and $65,000 per space. Mandating these costs through zoning “minimums” artificially inflates housing prices and Goods and Services. “Unbundling” these costs—allowing the market to price parking separately—lowers entry prices for residents and significantly increases the viability of high-density projects.

From Machine City to Living City

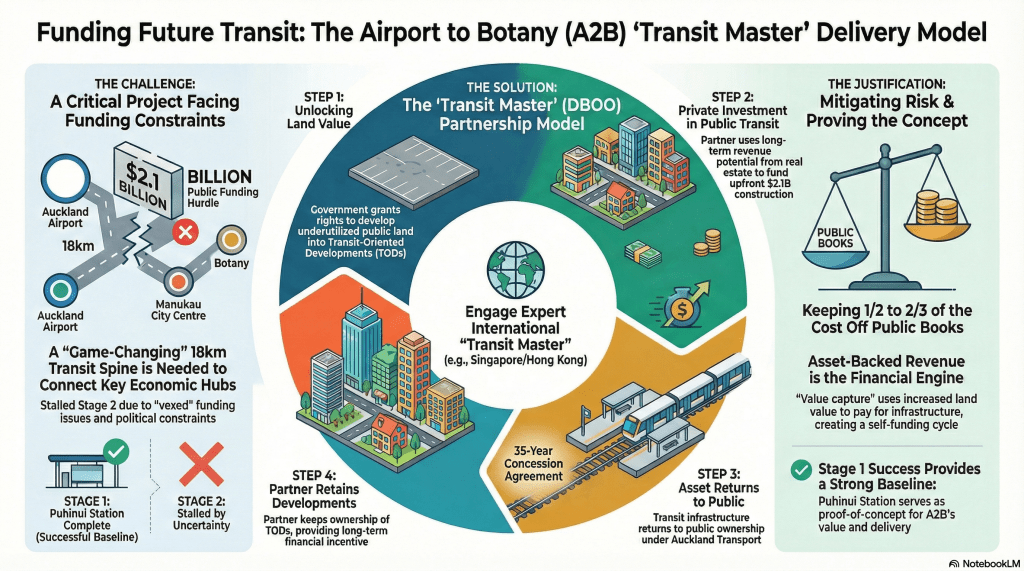

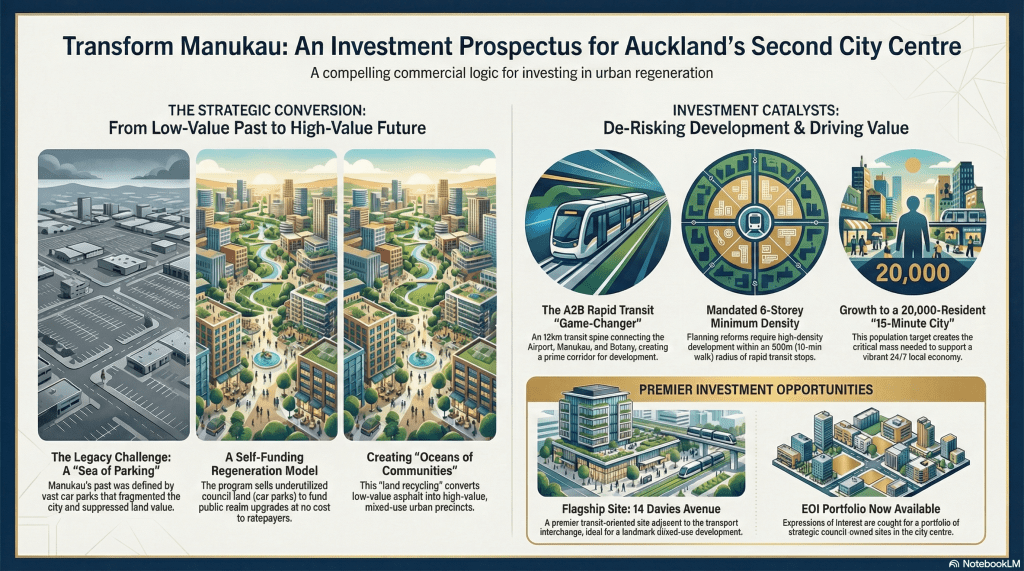

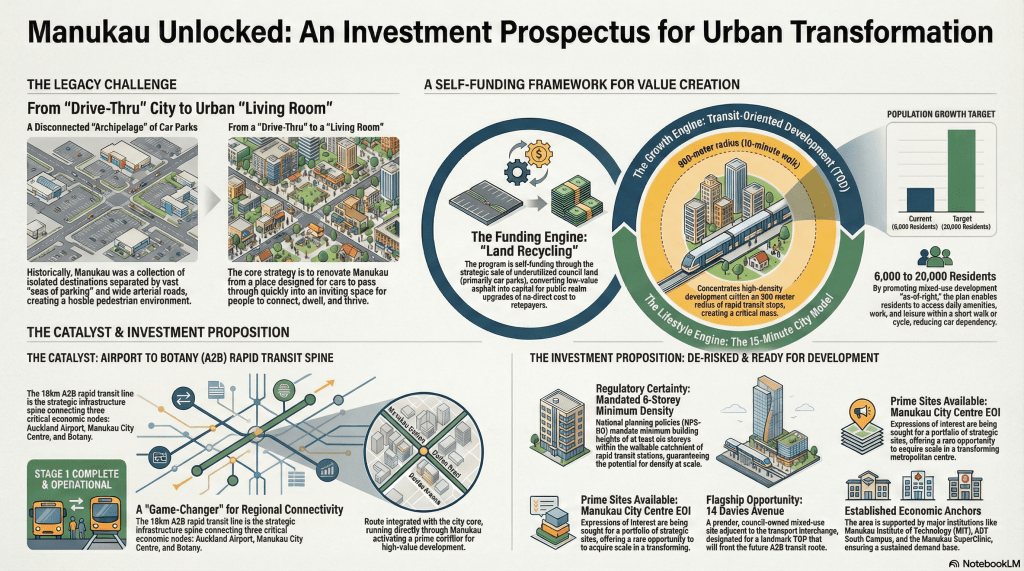

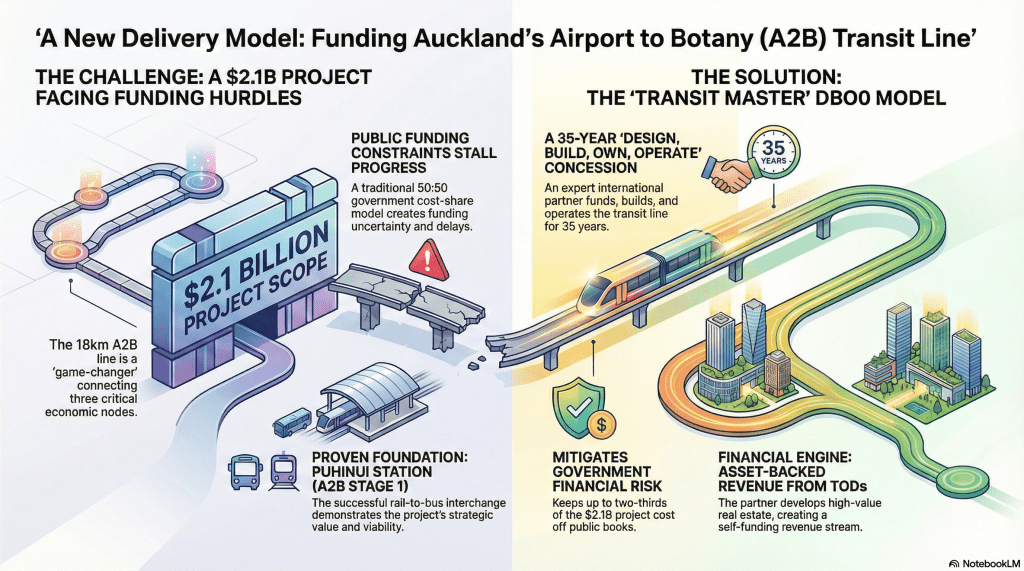

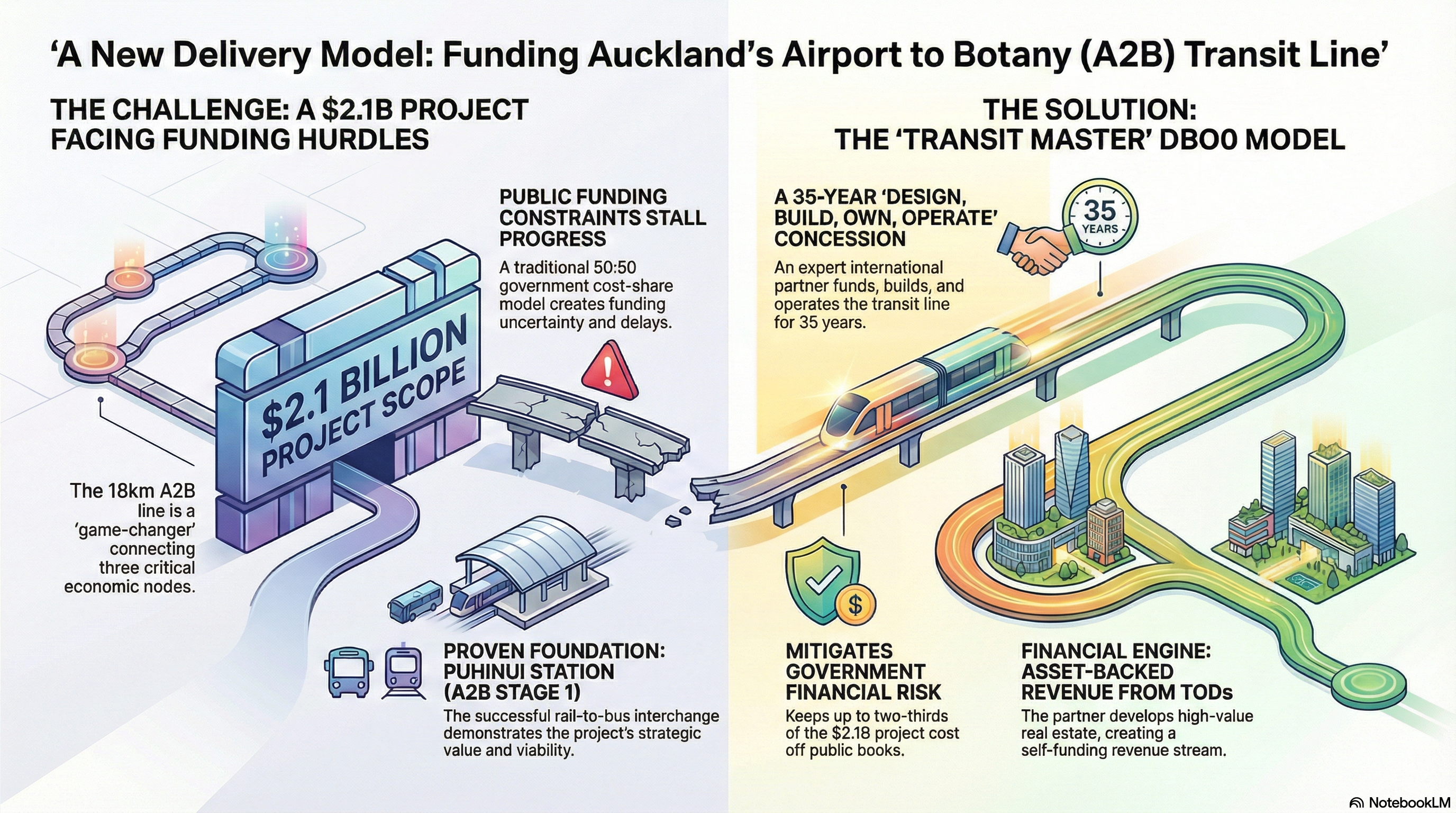

Note: Airport to Botany graphic illustrates the 33 Great South Road bus line incorrectly. A (light) rail loop using A2B and the Eastern Busway, Route 70 to Ellerslie then connecting to City Centre via Mangere at Onehunga using the Onehunga Line has been mentioned in the past.

4. The After-Dark Transition: Activating the “Linger Factor” and Social Safety

A city’s night economy depends on moving beyond “transactional” behaviour (drive-park-leave) to “experiential” behaviour (linger-socialize-spend). This is the Linger Factor. Patrons arriving by foot or transit stay longer because they are untethered from ticking parking meters and, crucially, the sobriety barrier. By removing the designated-driver constraint, transit-oriented neighbourhoods unlock significantly higher night-economy spending.

The contrast between the “Desolate City” and the “Humming City” is most visible at night. Empty car parks become unlit wastelands that invite danger. Conversely, transit hubs function as social anchors. In Manukau, the Republic Bar on Amersham Way thrives specifically due to its transit adjacency, generating social activity and safety that the car-dominated, desolate Station Road cannot match.

Strategically, repurposing parking into Active Edges—storefronts and cafes with glazing—provides “Eyes on the Street.” This passive surveillance makes environments inherently safer than parking lots. These social benefits are the direct result of a transit-based skeletal structure that replaces blank walls with human interaction.

| Takeaway or Strategy | Core Objective | Implementation Details | Projected Impact | Funding or Financial Model | Infrastructure Involved | Source |

| Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) | To maximize public investment in transport infrastructure by concentrating population density near rapid transit, creating a virtuous cycle of ridership and vibrancy. | Mandating minimum building heights of six storeys within an 800-meter (10-minute) walkshed of rapid transit stops, such as the 14 Davies Avenue flagship site. | Achieving a population target of over 20,000 residents to support a 24/7 city centre economy and reducing car dependency. | Value-capture via Public-Private Partnerships and the DBOO model. | Airport to Botany (A2B) rapid transit line; Manukau Train and Bus Stations. | 1, 2 |

| Design, Build, Own, and Operate (DBOO) Concession | To accelerate the delivery of major transit infrastructure by engaging international expertise and bypassing local funding constraints. | Engaging ‘Transit Masters’ (e.g., from Singapore or Hong Kong) to construct and operate the A2B line in exchange for a 35-year concession and TOD development rights. | Keeping half to two-thirds of the estimated $2.1 billion project cost off public balance sheets while delivering world-class transit. | Public-Private Partnership with TOD real estate as an asset-backed revenue stream for the private partner. | Airport to Botany (A2B) Rapid Transit line. | 1, 3, 4 |

| Land Recycling | To fund urban regeneration projects at no direct cost to ratepayers by converting low-value asphalt into high-value capital. | The strategic sale and redevelopment of underutilized council-owned land, primarily surface car parks like those at 14 Davies Avenue or Westfield Mall. | Generating approximately $140 million in revenue to be reinvested into public realm upgrades like parks and streetscapes. | Self-funding model through the sale of underutilized public assets. | Surface parking lots; Public realm assets (parks, plazas). | 1, 3-5 |

| Humanising the Public Realm (Road to Street) | To reclaim vehicle-dominated thoroughfares as social spaces and destinations for people rather than just routes for cars. | Tactical urbanism on Osterley Way (converting it to a 10km/h shared space) and the planned transformation of Ronwood Avenue into a boulevard. | Reduced ‘rat-running’ traffic, improved pedestrian safety, and creation of a ‘living room’ atmosphere for the city. | Reinvestment of land sale proceeds and NZTA funding (for pilot projects). | Osterley Way; Ronwood Avenue; Putney Way; Protected cycleways (‘Tim Tams’). | 1-3, 6 |

| Restoration of the Puhinui Stream (Te Aka Raataa) | To transform a ‘degraded drain’ into a primary green connector and ecological spine that stitches communities back to the city centre. | Ecological restoration and the construction of high-amenity walking/cycling paths linking Wiri to the Manukau Harbour and Botanic Gardens. | Restoring the ‘mauri’ (life force) of the waterway and providing safe, off-road movement corridors that bypass motorway barriers. | Funded by land recycling proceeds. | Puhinui Stream corridor; Barrowcliffe Bridge; Wiri Bridge. | 1-3, 7 |

| ‘As-of-Right’ Mixed-Use Zoning | To dismantle single-use segregation and empower the organic evolution of complete, walkable 15-minute neighbourhoods. | Permitting residential, commercial, and community activities to co-locate without complex resource consents, focusing on managing externalities. | Reduced car dependency, increased ‘eyes on the street’ for safety, and the development of a 24/7 city economy. | Not in source | Building blocks and street-level commercial frontages. | 1-3, 7 |

The delivery models

Manukau’s Transition

5. The Transit Skeleton: Density Follows Frequency

Transit-oriented urbanism is the structural backbone of the human city. Density is not an arbitrary choice; it is a requirement to maximize the utility of infrastructure.

Transit-Oriented Zoning Mandates

- Category 1 (Spine) Corridors: High-intensity rapid transit spines requiring a mandatory minimum of six storeys.

- Category 2 (Primary) Corridors: Frequent bus routes requiring a mandatory minimum of three storeys.

To mitigate “concrete fatigue” and ensure political palatability for high-density living, these mandates must integrate the 3-30-300 Rule for public health: every resident must see three trees, have 30% canopy cover, and be within 300m of green space.

Infrastructure like the Airport to Botany (A2B) line serves as a critical de-risking mechanism. By providing a reliable transit alternative, it allows developers to skip the $65,000-per-space parking burden, unlocking land for housing that would otherwise be wasted on vehicle storage.

6. The Policy Roadmap: From “Monopoly by Mandate” to Market-Led Reforms

The first step in urban liberation is removing “Parking Minimums”—a policy that has historically functioned as a monopoly by mandate, forcing land-use inefficiency. We must look to the Japanese Proof-of-Parking Model (Shako Shomei). By privatizing the cost of car storage—requiring proof of a private space before vehicle registration—Japan enables the “Pokémon House Aesthetic”: quirky, human-scaled developments where streets remain narrow, clean, and inviting.

The Auckland Parking Strategy provides the necessary tiered management roadmap:

- Tier 3 (Initiative-taking Management): Applied to high-readiness areas like Manukau. Parking is aggressively removed to prioritize bus lanes and cycleways.

- Tier 2 (Responsive for Commuters): Focusing on shifting commuters to sustainable modes while still supporting short-stay retail parking.

- Tier 1 (Responsive Management): Managing parking only as specific issues or safety concerns arise.

Central to this is the Park-Once District concept. This “intermodal bridge” consolidates parking into high-density structures, allowing users to park once and walk to multiple destinations, ending the “shop-to-shop car shuffle.”

Kerbside ROI per Square Meter:

- Car Parking Space: ~$950/day in local revenue.

- Dining Parklet: ~$1,660/day in local revenue.

From a policy standpoint, these reforms are not a “war on cars,” but a war on land-use inefficiency. The most productive use of a street is to host people, not to store machines.

7. Conclusion: The Habitats of 2026 and Beyond

The transition of the city from a “storage facility for machines” to a “habitat for humans” is a fiscal imperative. The “Asphalt Sea” of the 20th century is a legacy asset that no longer yields the returns required for a 24-hour economy.

By integrating transit and density, we trigger a Virtuous Cycle: Density supports high-frequency transit; transit supports foot traffic; and foot traffic supports the “linger factor” essential for economic vibrancy. We must reclaim the land from the asphalt trap. The urgency is clear: our economic productivity, social safety, and urban soul depend on restoring the human city.

Turning Manukau from Asphalt Grey to A Beating Heart of Gold

Note: Park and Ride illustrated is from Albany Metropolitan Centre which like Manukau needs its own transformation from asphalt to productive gold.