So you want a People First City? How do we design healthier city so that is a People First City?

Our lives have become sedentary as we went from people first cities to car first cities. And that has come at great cost which is being covered right through the Ben Does Planning series here on Talking Auckland. But as 2026 gets underway and you decide we must return to People First cities, but we need more tools to do so. Enter into the fray: How to Design that Healthier City through active design. Part 9 will continue this sub trend of the Ben Does Planning series through turning parking lots into communities!

But first, building those healthier, happier communities through active design!

An Introduction to Active Design: Building Healthier, Happier Communities

1. The Challenge: Why Our Built Environments Need a Change

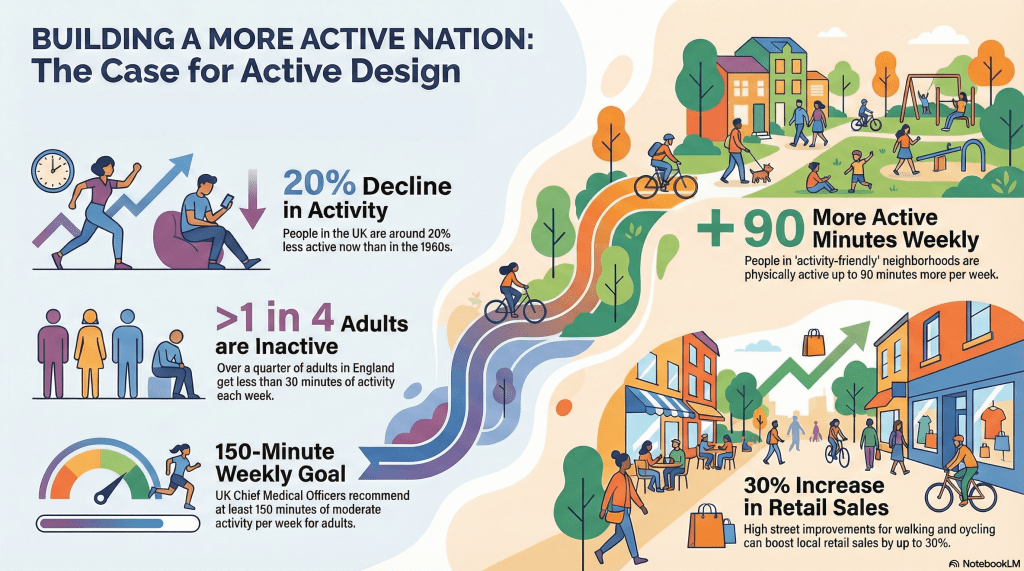

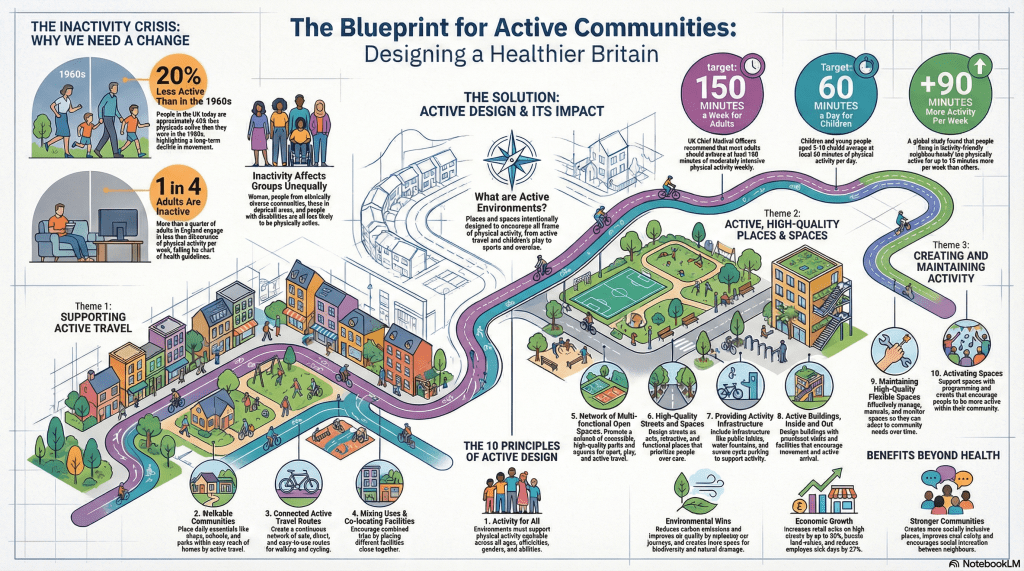

In recent decades, our daily lives have become increasingly sedentary. The design of our towns and cities often prioritizes convenience by car, unintentionally designing physical activity out of our routines. In the UK, people are now around 20% less active than they were in the 1960s, and more than one in four adults get less than 30 minutes of physical activity per week.

This decline in movement has contributed to a series of interconnected well-being crises that affect us all. The environments we build are directly shaping our health, happiness, and social fabric in ways we can no longer ignore.

- Rising Physical Health Issues: Our reliance on cars and poorly planned communities has fuelled a rising obesity crisis. The consequences can be severe, leading to chronic conditions like diabetes. In some areas, the impact is starkly visible, such as the community dialysis centre in Mangere, New Zealand, built specifically to treat end-stage kidney disease caused by diabetes. This represents a profound failure of urban planning and equitable transport investment, creating severe health crises that were otherwise preventable.

- Declining Mental Wellbeing: Environments designed around cars rather than people can lead to profound social disconnection. When we reduce opportunities for casual interaction—walking past neighbours, bumping into friends at a local park—we increase the risk of stress, depression, and anxiety. This lack of connection to both our community and the natural world takes a toll on our mental health.

- Deepening Social Inequities: A car-dependent system does not affect everyone equally. It disproportionately harms low-income households, Māori and Pacific communities, and women and girls. For those who cannot afford a car, it creates significant barriers to accessing education, employment, and essential services. For women and girls, safety concerns in poorly designed public spaces can severely limit their freedom and independence.

These challenges are not separate issues; they are intertwined symptoms of an environment that no longer serves our holistic well-being. Active Design offers an initiative-taking, evidence-based framework for reversing these trends.

So how to design a healthier city?

2. The Solution: What is Active Design?

Active Design is an approach to planning and designing our built and natural environments to make physical activity a natural and integrated part of everyday life. It seeks to reverse decades of car-centric planning by intentionally creating places that encourage and enable people to be more active.

It is about helping to create ‘active environments.

These “active environments” are not just about formal sports facilities like gyms or pitches. The goal is much broader, aiming to weave movement into the very fabric of our communities. Active Design encourages:

- Active Travel: Making it safe, convenient, and enjoyable to walk, cycle, or wheel to everyday destinations like school, work, or the shops.

- Children’s Play: Designing safe, engaging, and accessible public spaces where children have the freedom to play and be active.

- Outdoor Leisure: Creating and connecting parks, trails, and green spaces that invite people to relax, exercise, and connect with nature.

- Everyday Movement: Maximizing every opportunity for people to be active in their daily lives, from taking the stairs in a building to walking through a vibrant public square.

This guidance represents a credible, collaborative effort by leading UK health and transport bodies, including Sport England, Active Travel England, and the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), to create a unified vision for healthier communities.

By embedding these principles into how we shape our world, we can unlock a wide range of tangible benefits for everyone.

3. The ‘Why’: Key Benefits of Creating Active Environments

Creating active environments produces powerful, cascading benefits that extend far beyond physical fitness, improving community health, social justice, and environmental resilience.

| Benefit Category | How It Helps Our Communities | Why It Matters |

| Health & Wellbeing | Makes it easy to incorporate exercise into daily routines, like walking to school or shops. Increases contact with nature in green spaces, which is shown to improve mental health and reduce stress. | A 2016 study found people in ‘activity-friendly neighbourhoods’ were active for up to 90 minutes more per week. This helps combat obesity, diabetes, and mental health issues like depression and anxiety. |

| Social Equity & Justice | Provides free or low-cost ways to get around, reducing reliance on expensive cars. Creates safer, more connected communities where social interaction is more likely. Reduces barriers for people with reduced mobility, children, and older people to get around independently. | This tackles inequalities by improving access to jobs and services for all socio-economic groups. It also addresses the safety concerns that limit the freedom of women and girls. |

| Environmental Sustainability | Encourages a shift from car travel to walking and cycling, which reduces carbon emissions. Promotes multi-functional green spaces that can improve air quality, increase biodiversity, and help manage climate change impacts like flooding. | This directly supports critical goals like tackling climate change and improving the local environment for everyone. |

These benefits are not accidental; they are the direct result of applying a clear and practical set of design principles.

4. The ‘How’: The Ten Principles of Active Design

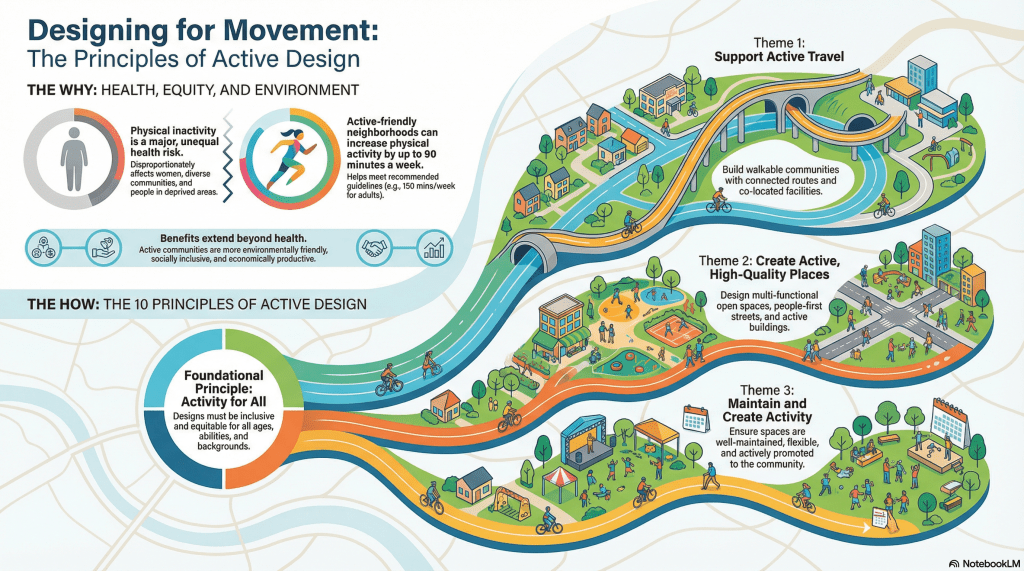

The Ten Principles of Active Design provide a comprehensive blueprint for planners, designers, and community leaders to create active environments. They are organized around a foundational principle and three core themes.

Foundational Principle: Activity for All. Environments must be designed equitably to support activity for everyone, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, or ability.

The Three Core Themes

- Theme 1: Supporting Active Travel

- Principle 2 – Walkable Communities: Placing daily essentials like shops and schools within an easy 800m walk from homes.

- Principle 3 – Connected Active Travel Routes: Creating a safe, direct, and continuous network of paths for walking and cycling.

- Principle 4 – Mixing Uses & Co-locating Facilities: Grouping different destinations together to encourage people to combine trips and walk between them.

- Theme 2: Active, High-Quality Places & Spaces

- Principle 5 – Network of Multi-functional Open Spaces: Designing accessible parks and public areas for a variety of activities, from sports to relaxation.

- Principle 6 – High-Quality Streets & Spaces: Making streets safe, attractive, and people-focused rather than just corridors for cars.

- Principle 7 – Providing Activity Infrastructure: Including essential supports like secure bike parking, public toilets, benches, and water fountains.

- Principle 8 – Active Buildings, Inside & Out: Designing buildings that encourage movement with prominent stairs and easy access for pedestrians and cyclists.

- Theme 3: Creating & Maintaining Activity

- Principle 9 – Maintaining High-Quality Flexible Spaces: Ensuring spaces are well-managed and can adapt to the changing needs of the community over time.

- Principle 10 – Activating Spaces: Actively promoting events and programs that encourage people to use the spaces and get involved.

These principles provide a powerful framework, but their true impact becomes clear when we see them applied in the real world.

5. Active Design in Action: The Houlton Community

The community of Houlton, a new development of 6,200 homes in Rugby, Warwickshire, serves as an excellent real-world example of Active Design in practice. It was designed from the ground up with health and wellbeing as core objectives, demonstrating how these principles can be woven together to create a thriving community.

Key lessons from the Houlton project include:

- Prioritize Green Space: The extensive network of green open spaces was the most critical element. It not only enabled physical activity through trails and parks but also served as the social glue that brought the new community together.

- Invest for the Long-Term: The developer maintained a continuing interest in the quality of the site, investing in high-quality infrastructure and spaces. This long-term vision proved to be good business, leading to faster home sales and higher property values.

- Be Flexible: An ongoing, flexible approach to design allowed the community to adapt as it grew. This responsiveness ensured that new opportunities to improve health and wellbeing could be seized in consultation with residents.

- Encourage Active Habits Early: By delivering schools, parks, local centres, and community facilities before or alongside the first homes, the developer helped residents form active travel habits from day one, making walking and cycling the natural choice.

Houlton shows that designing for health is not just a social good but a sound economic strategy. It also highlights the importance of shifting our fundamental mindset about how we share public space.

6. A New Perspective: Shifting Our Mindset

Ultimately, creating healthier communities requires more than just new infrastructure; it demands a change in how we think about our rights and responsibilities in the public realm. For too long, planning has prioritized the movement of cars, treating it as an absolute right rather than a privilege that must be balanced with the needs of everyone else.

This distinction is crucial:

“The larger point being is that our planning has been far too long focused on the elites driving four-wheeled metal boxes and treating it as a “right” rather than privilege.

The difference being “Right” treats the environment as ME and damn everyone else while “Privilege” treats the environment as sharing with everyone else equally – on the road space.“

Adopting a mindset of shared privilege is the foundational first step. It allows us to see our streets not as corridors for cars, but as public spaces for people—places where children can play, neighbours can connect, and communities can thrive. This is the heart of Active Design and the key to building more active, healthy, and equitable communities for all.

Active Design: Creating Environments for Health and Wellbeing.

Note: AI generated summarising the Active Design manual, found at the bottom of this blog post

With the introduction out of the way, how do we and I mean everyone get active design principles into local planning policy. And by local I mean by both Councils, and Central Government given the Government Policy Statement, and National Land Transport Fund in Aotearoa determine funding levels for such investments.

A Proposal for Integrating Active Design Principles into Local Planning Policy

1.0 Introduction: The Urgent Case for Health-Centric Urban Planning

Modern urban environments, while offering undeniable economic and cultural benefits, have inadvertently engineered physical activity out of daily life. The convenience of car-centric design has come at a significant cost, contributing to a series of interconnected public health, environmental, and social challenges that demand immediate and strategic intervention. The current planning model, which prioritizes motor vehicles, has created systemic barriers to active living, and it is imperative that we evolve our approach to place-making.

The public health data is stark and compelling. In the United Kingdom, people are approximately 20% less active now than they were in the 1960s. Today in England, more than one in four adults performs less than 30 minutes of physical activity per week, falling far short of recommended levels for maintaining basic health. This widespread inactivity is a primary driver of the rising obesity crisis, which places an immense and growing strain on our healthcare system and national economy.

However, the consequences of our current planning paradigm extend far beyond physical health. The academic consensus points to an interlinked crisis of rising obesity, climate change, and social inequity, all of which are exacerbated by car-dependent urban design. This model not only contributes to transport-related carbon emissions and poor air quality but also fosters social disconnection, stress, and anxiety. It creates deep injustices for those without access to a private vehicle, including many low-income households, women, and young people, limiting their access to the basic building blocks of wellbeing.

This proposal argues that integrating Active Design principles into our local planning policy is not a niche interest but a fundamental and necessary evolution. It is an evidence-based framework for creating healthier, more equitable, and more sustainable communities. The following sections will define this framework, articulate its comprehensive benefits, and provide a clear roadmap for its implementation.

2.0 Defining Active Design: A Proven Framework for Healthier Communities

Active Design is a comprehensive, evidence-based approach to planning and urban design that deliberately integrates opportunities for physical activity into the built and natural environment. The goal is to create “active environments”—places where walking, cycling, sport, and play are convenient, attractive, and safe choices for everyone. This updated guidance is the result of a powerful collaboration between Sport England, Active Travel England, and the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, reflecting a unified commitment to strengthening the links between health, urban design, and planning.

The framework is structured around ten core principles that provide a practical toolkit for planners, designers, and developers. These principles are designed to be flexible and adaptable to a variety of contexts, from large-scale new communities to the regeneration of existing town centres.

Foundational Principle

- Principle 1: Activity for all — Environments should support physical activity equitably across all ages, ethnicities, genders, and abilities.

Theme 1: Supporting Active Travel

- Principle 2: Walkable communities — Facilities for daily essentials and recreation should be within easy reach of each other by active travel means.

- Principle 3: Providing connected active travel routes — Encourage active travel for all ages and abilities by creating a continuous network of routes connecting places safely and directly.

- Principle 4: Mixing uses and co-locating facilities — People are more likely to combine trips and use active travel to get to destinations with multiple reasons to visit.

Theme 2: Active, High-Quality Places & Spaces

- Principle 5: Network of multi-functional open spaces — Accessible and high-quality open space should be promoted across cities, towns, and villages to provide opportunities for sport and physical activity.

- Principle 6: High-quality streets and spaces — Streets and outdoor public spaces should be safe, attractive, functional, prioritise people and able to host a mix of uses.

- Principle 7: Providing activity infrastructure — Infrastructure to enable sport, recreation and physical activity to take place should be provided across all contexts to facilitate activity for all.

- Principle 8: Active buildings, inside and out — Buildings should be designed with providing opportunities for physical activity at the forefront.

Theme 3: Creating and Maintaining Activity

- Principle 9: Maintaining high-quality flexible spaces — Spaces and facilities should be effectively maintained and managed to support physical activity and adapted as needed.

- Principle 10: Activating spaces — The provision of spaces and facilities should be supported by a commitment to activate them, encouraging people to be more physically active.

These ten principles offer a clear and holistic toolkit for shaping healthier communities. Their successful application delivers demonstrable and multifaceted benefits that create a powerful return on investment for the entire community.

3.0 The Multifaceted Benefits of Integrating Active Design

The adoption of Active Design principles yields a powerful return on investment that extends far beyond public health. By creating environments that encourage physical activity, we simultaneously address critical economic, environmental, and social objectives. This section analyses the interconnected advantages across four key pillars: public health, economic growth, environmental sustainability, and social equity.

3.1 Enhancing Public Health and Wellbeing

The direct health impacts of Active Design are significant and well-documented. A landmark 2016 study of fourteen cities and towns found that residents of ‘activity-friendly neighbourhoods’ are physically active for up to 90 minutes more per week. This increase directly addresses the inactivity crisis by embedding exercise into daily routines, reducing the risk of chronic conditions such as obesity and diabetes.

Beyond physical health, active environments are crucial for mental wellbeing. A planning model built around car dependence contributes to social disconnection, stress, and anxiety. In contrast, walkable, bikeable communities with high-quality public spaces reconnect people with each other and with the natural world, fostering social connection and reducing mental distress—key supporters of spiritual, cultural, and emotional wellbeing.

3.2 Driving Sustainable Economic Growth

High-quality, active environments are a direct driver of economic value and sustainable growth. The Houlton development in Warwickshire serves as a compelling model. By prioritizing a network of open spaces and facilities within easy reach, the development achieved “a considerably higher sales rate of homes than the surrounding area” in its preliminary stages and is now seeing “increase sales values.” This demonstrates a clear market demand for the quality of life offered by Active Design.

The return on investment is quantifiable and profound. The Oxfordshire “Wayfinding for Healthy Lives” project, which created intuitive circular routes marked by painted footprints on the pavement and clear signage, yielded a social return of £18.23 for every £1 invested. Furthermore, research shows that every dollar spent on high-quality biking infrastructure can bring back ten dollars or more in health sector savings, proving that designing for activity is a fiscally responsible long-term strategy.

3.3 Advancing Environmental Sustainability and Climate Resilience

Active Design principles are intrinsically aligned with broader environmental and climate policy objectives. By promoting active travel, the framework directly supports a reduction in transport-related carbon emissions and improves local air quality. Interventions such as creating networks of multifunctional greenspace and integrating natural habitats contribute to carbon capture and support biodiversity net gain.

Specific design elements championed by the framework enhance climate resilience. The strategic use of tree planting provides natural cooling and shade, regulating air temperature during hotter months. The integration of sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) and rain gardens improves drainage and mitigates flood risk. These measures create more resilient communities while also making them more pleasant and attractive places to live.

3.4 Fostering Social Equity and Inclusion

Active Design is a critical tool for tackling social and health inequalities. The current over-reliance on cars creates “deep social well-being injustices,” particularly for low-income households, women, and girls, who may have limited access to a private vehicle and feel unsafe using public transport or walking in poorly designed environments. Active Design addresses this by creating safe, connected, and accessible networks for everyone.

A central tenet of this approach is the creation of child-friendly cities. As Professor Robin Kearns argues, designing streets and neighbourhoods that are safe for children’s independent travel is a matter of citizenship, allowing them to explore their local environment. This fosters independence and, crucially, embeds lifelong habits of physical activity, building a healthier future generation from the ground up.

Together, these benefits illustrate that Active Design is a comprehensive approach that delivers compounding value. The following case studies display how these principles have been successfully implemented in the real world.

4.0 Active Design in Practice: Policy Precedents and Successful Case Studies

The Active Design framework is not a theoretical exercise; it is a proven approach already aligned with national policy and successfully implemented in diverse contexts across England. These real-world examples demonstrate the feasibility and tangible benefits of embedding health and activity into the core of the planning process.

4.1 National Policy Alignment

Integrating Active Design is a logical extension of existing policy direction. The principles are fully consistent with the guidance and recommendations set out in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), the National Design Guide, and the National Model Design Code. Adopting this framework will therefore strengthen, rather than contradict, our commitment to established national planning priorities.

4.2 Case Study: Houlton, Warwickshire – A Model for New Large-Scale Communities

This 6,200-home development on a former brownfield site exemplifies how to build a complete, active new community from the ground up, with health and wellbeing considered at every scale.

Key Success Factors and Lessons Learned

- Master Developer Leadership: A single expert developer (Urban Civic) delivered the core infrastructure—including open spaces, active travel networks, and schools—ensuring long-term investment in quality and place-making.

- Early Infrastructure Delivery: Community facilities and schools were delivered prior to or alongside the first homes, establishing active travel habits from day one and making the community attractive to new residents.

- Economic Value of Quality: The focus on high-quality open spaces and walkable amenities directly translated into a higher sales rate and increased home values, demonstrating a clear market reward for clever design.

- Flexible Master planning: An overarching masterplan set the core structure, but detailed design codes for later phases allowed for flexibility and responsiveness to changing trends and resident feedback.

4.3 Case Study: Nottingham – A City-Wide Active Travel Transformation

Nottingham is engaged in an ambitious, ongoing program to transform its streets for active travel by creating an extensive network of segregated cycle routes and improving the city centre public realm.

Key Success Factors and Lessons Learned

- Securing Central Government Funding: A strong political ambition, backed by a clear strategic network design, enabled the city to secure £161m from the Department for Transport’s Transforming Cities Fund.

- Strategic Network Approach: Rather than piecemeal improvements, the city focused on delivering continuous, connected corridors linking key destinations, which is critical for encouraging widespread adoption of cycling.

- Phased Delivery to Address Inequity: The rollout of the network was strategically phased to prioritize connections in more deprived neighbourhoods and to key destinations like universities and hospitals.

- Integrating Active Travel with Public Realm: The program combined new cycleways with major improvements to the city centre environment, removing private vehicles from key streets to create new, vibrant public spaces.

4.4 Case Study: Stevenage – A Framework for Urban Regeneration

As the UK’s first post-war New Town, Stevenage is leveraging an ambitious town centre regeneration program to provide new homes, jobs, and facilities within a public realm that prioritizes walking and cycling.

Key Success Factors and Lessons Learned

- A Guiding Masterplan: The Stevenage Central Framework provided a clear spatial vision for development, giving certainty to partners and guiding investment in key connections and public realm improvements.

- Multi-Partner Delivery Board: The creation of a Stevenage Development Board, bringing together public, private, and non-profit stakeholders, has provided strategic oversight and helped de-politicize the process.

- Testing Ideas with Temporary Use: The council has actively used temporary installations in vacant plots and public squares to evaluate ideas, generate activity, and engage the community before committing to permanent changes.

- Revitalizing a Legacy Network: The program is focused on upgrading and improving the town’s existing but underused network of segregated cycleways, leveraging a key asset to support future growth.

These successful examples provide a clear and compelling precedent. They demonstrate that with strategic vision and a commitment to the principles of Active Design, it is possible to deliver development that fosters health, prosperity, and resilience. The next section outlines a roadmap for translating this vision into local policy.

5.0 A Roadmap for Integration: Proposed Policy Actions

This section provides concrete, actionable recommendations for embedding Active Design principles directly into our local authority’s planning documents and day-to-day processes. Based on the guidance provided by Sport England and its partners, these actions will ensure that the creation of healthy, active environments becomes a central objective of all future development.

The following policy actions are proposed:

- Develop and adopt Local Plan and Neighbourhood Plan policies that explicitly support and, where appropriate, require the creation of active environments and opportunities for physical activity.

- Integrate the Ten Principles of Active Design as a core framework for the development of all local Design Codes, Masterplans, and Development Briefs for specific sites.

- Utilize the Active Design principles to structure and inform pre-application discussions with developers, establishing the importance of health and wellbeing outcomes from the earliest stages of a project.

- Incorporate the Active Design checklist as a formal tool for assessing and making decisions on planning applications and use it to help define and secure relevant planning obligations.

- Identify and support key public projects and activation programmes that can deliver physical activity benefits.

- Engage proactively with public health professionals and require the use of Health Impact Assessments (HIAs) to support major planning applications and ensure health equity is considered.

- Develop and update Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plans (LCWIPs) and other transport plans to align with the active travel principles of the framework.

- Monitor and manage places post-development to ensure that they continue to support and enable physical activity for all members of the community over the long term.

Adopting these measures will institutionalize a focus on health and wellbeing, ensuring that every new development contributes to a legacy of a more active, vibrant, and resilient community.

6.0 Conclusion and Formal Recommendation

The evidence is clear: the choice is not between development and health, but about pursuing a model of development that actively enhances community wellbeing, economic vitality, and environmental resilience. By systematically designing physical activity back into our daily lives, we can address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. The Active Design framework provides a proven, practical, and nationally endorsed pathway to achieve this vital goal.

It is therefore formally proposed that the Local Planning Authority begin the process of integrating the Ten Principles of Active Design into the forthcoming Local Plan Review and embedding them as a core component of all new Supplementary Planning Documents, local Design Codes, and associated planning guidance.

This strategic policy shift represents an initiative-taking investment in the long-term prosperity of our community. It is a commitment to creating a healthier, more active, and more equitable future for all residents.