Tokyo inspires what Manukau could be

As the Parking mini-series continues on, we look to the urban and transit masters in Tokyo to assist the car centric Manukau City centre!

Day and Night, a Tale of Two Cities

Parking and Placemaking: A Comparative Case Study of Urban Development in Tokyo and Manukau

1.0 Introduction: Two Cities, Two Philosophies

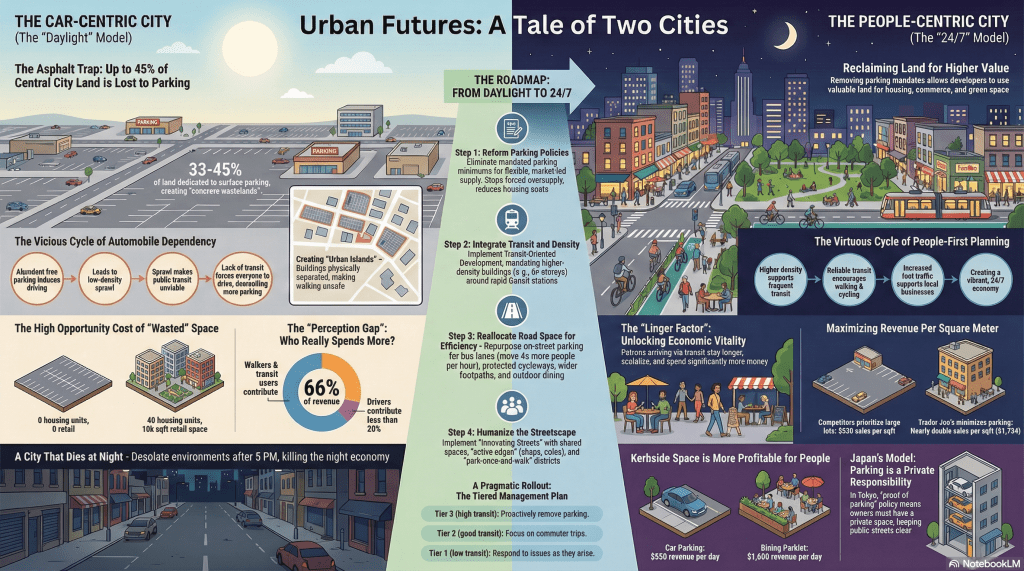

The provision of car parking is not a simple matter of convenience; it is a critical urban design choice with profound and lasting impacts on a city’s economic vitality, liveability, and environmental sustainability. How a city manages the temporary storage of private vehicles fundamentally shapes its physical form, influences travel behaviour, and determines whether its valuable land is dedicated to people or to cars. The consequences of this choice define the character and prosperity of a place.

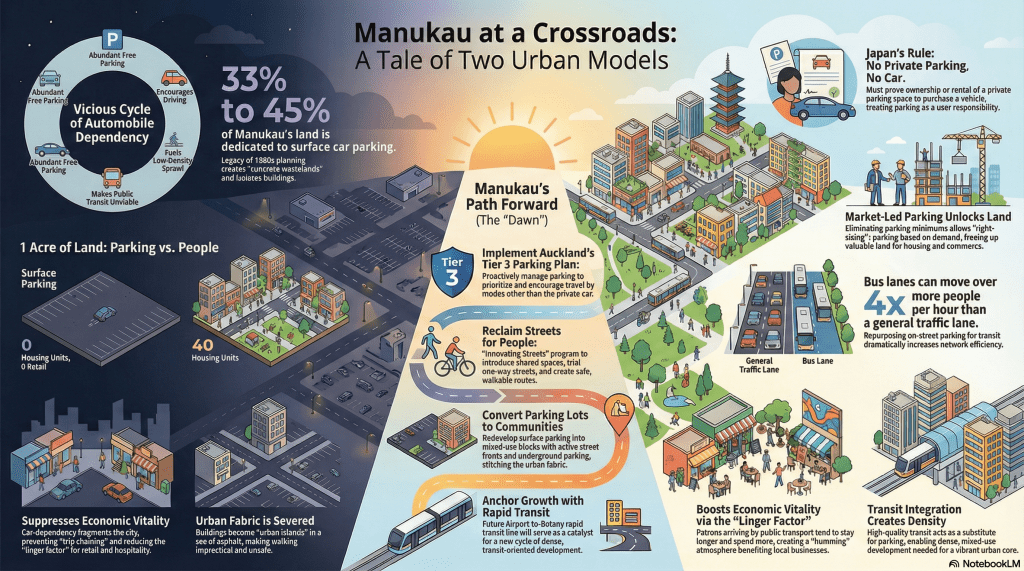

This case study examines two cities that represent fundamentally different philosophies of urban planning and vehicle management: Manukau in Auckland, New Zealand, and Tokyo, Japan. Manukau embodies the legacy of 20th-century, car-centric design, where planning regulations prioritized the automobile, resulting in a landscape dominated by surface parking. Tokyo, in stark contrast, offers a people-centric model that deliberately de-prioritizes the private car in public space, treating parking as a private responsibility to foster highly efficient land use and vibrant street-level communities.

The objective of this document is to analyse these contrasting strategies, evaluate their respective economic and community outcomes, and distil actionable insights for urban planners, developers, and policymakers. By comparing the sprawling, fragmented environment of Manukau with the dense, walkable fabric of Tokyo, we can illuminate the hidden costs of auto-dependency and the tangible benefits of a people-first approach to urban development.

This analysis will proceed in four parts. First, we will explore the historical context and consequences of Manukau’s auto-centric legacy. Second, we will examine Tokyo’s foundational policies and their effect on its urban form. Third, a direct comparative analysis will highlight the trade-offs between the two models. Finally, we will outline a blueprint for transformation, presenting a framework of policy recommendations designed to help cities transition from prioritizing parking to creating prosperous, human-scaled places.

2.0 The Auto-Centric Legacy: Manukau, Auckland

To understand the challenges facing Manukau today, it is essential to analyse its development history. The city centre is a quintessential example of mid-20th-century planning, an era when the automobile was seen as the primary mode of transport and the symbol of progress. This foundational decision to prioritize vehicle access and storage has created a landscape that now struggles with economic inefficiency and social fragmentation. Manukau’s story is a powerful illustration of how outdated planning rules can lock a city into a cycle of car dependency.

Historical Context: The Making of a Car-Dependent Centre

Manukau was designed in the 1960s as a CBD for South Auckland, a strategic role it is now expanding upon as it morphs into a Super Metropolitan Centre for the wider region. It was built upon a planning philosophy where the “car was king above all else.” This approach was codified by regulations originating in the 1950s, which mandated that developers provide a high number of car parks for every new building. These requirements were not based on average daily use but on accommodating theoretical peak demand—the “Boxing Day madness” scenario—ensuring that vast tracts of land were set aside for parking that would sit underutilized for most of the year.

The visual record chronicles this transformation with stark clarity. A 1976 photograph shows the Manukau City Council building on a blank canvas of pastoral land, an area of immense potential. By 1981, we see the physical manifestation of a car-centric ideology taking root, with new buildings isolated from one another by extensive surface parking lots. The 2023 aerial view reveals the ossified outcome of those decisions: a landscape locked in by asphalt, where development potential has been paved over.

Consequences of Prioritizing Parking

The urban form of Manukau today is a direct outcome of this car-first philosophy. The landscape is characterized by “urban islands” and “urban fragmentation,” where large buildings are disconnected from each other by expansive parking lots, rendering walking an unpleasant and often impractical experience. A land use analysis indicates that a remarkable 33% to 45% of all land in the Manukau City Centre is dedicated to surface car parking, an inefficient use of valuable urban space best described as a “concrete wasteland.”

The trade-off between dedicating land to parking versus more productive uses is stark. A one-acre surface parking lot and a one-acre walkable neighbourhood represent two vastly different visions for a city, with dramatically different outcomes for the community.

| Metric | One-Acre Surface Parking Lot | One-Acre Walkable Neighbourhood |

| Parking Spots | 120 | Minimal |

| Housing Units | 0 | 40 |

| Retail Space | 0 sqft | 10,000 sqft |

| Usable Open Space | 0% | 55% |

Source: Cul-de-sac, “Development not parking” graphic.

The Hidden Economic Burden

The vast parking lots of Manukau represent a significant opportunity cost—the value of the best alternative forgone. This land could be generating far greater economic and social value if it were used for retail, offices, housing, or public parks. Its current use for inefficient vehicle storage actively suppresses the economic and social potential of the entire metropolitan centre, creating a direct causal link between the concrete wasteland and unrealized regional prosperity.

Furthermore, the provision of “free parking” is an economic misnomer. The substantial costs associated with land acquisition, construction, and maintenance are hidden and passed on to all consumers. As detailed in analyses from “Talking Southern Auckland,” these costs are built into the prices of goods and services. Whether a person drives, walks, or takes public transport, a portion of what they pay subsidizes the “free” parking outside. This creates a market distortion that incentivizes driving and penalizes those who use more sustainable modes of transport.

This auto-centric model, with its fragmented landscape and hidden economic burdens, stands in sharp contrast to the alternative path taken by Tokyo.

3.0 A People-First Paradigm: Tokyo, Japan

The Tokyo model represents a radical departure from the assumptions that have long governed urban planning in the Anglo-world. It demonstrates that a dense, vibrant, and economically prosperous metropolis can thrive by deliberately de-prioritizing the private vehicle in the public realm. The strategic importance of Tokyo’s approach lies in its simple yet transformative premise: the storage of a private vehicle is a private responsibility, not a public subsidy. This foundational principle has produced an urban form that prioritizes people, walkability, and community-level economic exchange.

The Foundational Policy: Proof of Parking

The core legal principle governing vehicle ownership in Japan is remarkably straightforward: to purchase a vehicle, an individual must first provide official proof that they own or have a long-term lease for a suitable private off-street parking space. This policy, known as “proof of parking,” fundamentally alters the relationship between the car and the city. It eliminates the expectation that the public will provide free or subsidized storage for private property on public streets. As one analysis succinctly puts it:

“There is no assumption that motorists have the right to store their vehicle in public spaces for free.”

This single policy has cascading effects on the entire urban environment. By making parking a private good that individuals must secure and pay for directly, it removes the incentive for local governments to mandate excessive parking in new developments or to dedicate valuable kerbside space to vehicle storage.

Urban Form and Community Outcomes

The result of this policy is immediately visible in Tokyo’s streetscape. The visual evidence reveals human-scaled laneways and vibrant commercial frontages that open directly onto the pedestrian realm. The absence of on-street parking creates a sense of energy derived from a public realm uncluttered by the storage of private vehicles. This allows for narrower, more intimate streets that foster a high degree of walkability and human interaction.

This people-first environment directly supports a vibrant local economy. Businesses connect seamlessly with passersby, encouraging spontaneous commercial activity. The walkable, human-scaled design promotes community interaction and ensures that streets function as social spaces, not just as corridors for vehicles.

In summary, the Japanese model treats parking as a private responsibility, a decision that has fundamentally reshaped the public realm and its economic function. By freeing the streets from the burden of vehicle storage, Tokyo has cultivated an urban fabric that is efficient, economically dynamic, and built for people, setting the stage for a powerful comparison with Manukau.

4.0 Comparative Analysis: Place vs. Parking

A direct comparison of the Manukau and Tokyo models reveals the profound trade-offs inherent in each approach to parking management. This analysis moves beyond abstract philosophy to highlight the tangible impacts on land use, economic productivity, and community well-being. The evidence demonstrates an obvious choice between subsidizing inefficient vehicle storage and fostering vibrant, people-oriented places.

| Feature | Manukau (Auto-Centric Model) | Tokyo (People-Centric Model) |

| Core Philosophy | The car is king. Public space must accommodate peak vehicle demand. | People come first. Parking is a private responsibility. |

| Land Use Efficiency | Highly inefficient. An estimated 33% to 45% of the city centre is dedicated to surface parking. | Highly efficient. The absence of on-street parking and minimums allows for a dense, walkable urban fabric. |

| Economic Impact | Hidden costs of “free” parking are passed on to all consumers. High opportunity cost for land used as surface parking. | Vibrant street-level commerce is supported by active frontages and high foot traffic. Land is used for its highest economic purpose. |

| Community Experience | “Urban fragmentation” and “urban islands” create a disjointed environment hostile to pedestrians. | “Inviting” and walkable streets foster community interaction, safety, and a keen sense of place. |

| Public vs. Private Responsibility | Public policy (parking minimums) mandates the private provision of parking, which is then subsidized by the public through higher prices. | Vehicle storage is a private responsibility, freeing up public space for community and economic use. |

The Economics of Kerbside Space

The economic argument becomes even more compelling when examining the revenue-generating potential of a single kerbside space. Data from recent studies illustrates the dramatic difference in economic activity generated when this space is allocated to uses other than storing a single, stationary car.

- Car Parking: Generates an estimated $1,050 in revenue per month.

- Parklet (Outdoor Dining): Generates an average additional revenue of $8,940 per month for adjacent businesses.

- Bike Parking: A single kerbside space repurposed for bike parking generates an estimated 1,700** in daily revenue for local businesses, compared to **950 for a car space.

These figures provide a clear economic rationale for reallocating kerbside space. The decision to prioritize car parking is, in effect, a decision to accept a lower-value economic use for prime public real estate. The evidence indicates an obvious choice between subsidizing inefficient vehicle storage and fostering economically productive, people-oriented places. This reality necessitates a fundamental rethinking of the policies that have created car-dependent cities like Manukau.

5.0 A Blueprint for Transformation: Policy and Strategy

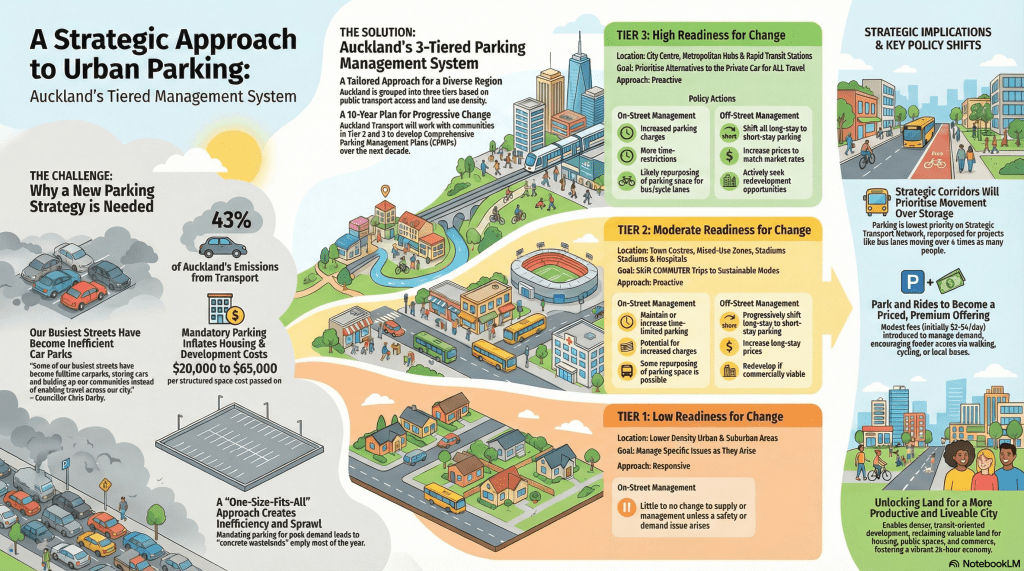

This section moves from analysis to action, outlining a practical framework for policymakers and developers seeking to transition from a car-centric to a people-centric model. The strategies presented are grounded in a growing global consensus and are already being adopted by forward-thinking cities. Auckland’s own recent strategic shift provides a powerful, real-world example of how a city can begin to unwind its auto-centric legacy and reclaim its urban spaces for people and productivity.

Challenging the Status Quo: Eliminating Parking Minimums

The root of many urban inefficiencies lies in government-mandated parking minimums. These outdated regulations force developers to build a predetermined number of parking spaces, regardless of actual demand or local context. This practice artificially inflates development costs, creates market distortions, and stifles efficient land use. Critically, high parking minimums also hinder the re-use, redevelopment, and sensitive infill of older areas with small building sites, preventing organic urban regeneration.

The movement to eliminate parking minimums is not a partisan issue but a matter of sound economic and environmental policy. This is demonstrated by the rare agreement on the topic between figures like Green Party MP Julie-Ann Genter and the market-oriented think tank, the New Zealand Initiative. Both recognize that removing these mandates allows the market to determine parking supply more efficiently, reducing costs and encouraging better urban design.

Auckland’s New Playbook: The 2022 Draft Parking Strategy

Auckland has begun to formally codify this new thinking in its 2022 Draft Parking Strategy, which serves as an excellent model for reform. The strategy moves away from a one-size-fits-all approach and introduces a sophisticated, context-sensitive framework for managing public space.

The core concepts include:

- Prioritization of Kerbside Space: The strategy establishes a new hierarchy for the use of valuable kerbside space on the Strategic Transport Network. Safety improvements, public transport, cycleways, and public space enhancements are all given higher priority than general vehicle parking, which is ranked last. This fundamentally reframes the purpose of the street from vehicle storage to moving people and enhancing place.

- A Tiered, Context-Sensitive Approach: Recognizing that Auckland is a diverse region, the strategy creates a three-tiered system for parking management: “Low,” “Moderate,” and “High Readiness for Change.” Critically, Manukau is designated a Tier 3 area, signifying it as a location with good public transport access where parking will be proactively managed to encourage a significant shift away from private car use. Designating Manukau as a Tier 3 area is a direct policy response to the “urban fragmentation” and economic underperformance caused by its legacy of parking minimums. This designation empowers planners to proactively dismantle the very conditions—the “concrete wastelands”—that have hindered its development for decades.

- Repurposing Road Space: To accelerate project delivery, the strategy states that on the Strategic Transport Network, parking will be automatically repurposed for projects that improve the movement of people and goods. This policy is designed to save time and reduce the significant costs associated with road-widening, allowing the city to deliver more projects, faster.

From Parking Lots to Thriving Neighbourhoods

Beyond managing on-street parking, a key goal is the transformation of the vast surface parking lots that fragment urban centres. The modern alternative is the creation of “park-once-and-walk districts.” This model consolidates parking into shared, strategically located facilities, freeing up individual sites from parking mandates and allowing for the creation of contiguous, walkable blocks where buildings engage the street instead of being set back behind private lots. The “Pavement Buster’s Guide” provides a list of actionable ideas for achieving this transformation:

- Reduce or eliminate off-street parking mandates to free developers from inefficient requirements.

- Encourage structured and underground parking instead of sprawling surface lots.

- Promote infill and brownfield redevelopment on existing paved areas.

- Implement “Complete Streets” policies and reallocate road space to better serve all users, including pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders.

These policy shifts provide a clear and practical pathway to unlocking the immense economic and social value currently dormant under asphalt. They are the essential tools for transforming car-dominated spaces into thriving, people-oriented neighbourhoods.

6.0 Conclusion and Actionable Recommendations

This comparative case study demonstrates that a city’s approach to car parking is a defining choice between creating sterile, inefficient spaces for vehicle storage and fostering vibrant, economically resilient places for people. The auto-centric legacy of Manukau, with its fragmented landscape and hidden economic burdens, stands in stark contrast to the people-first paradigm of Tokyo. Auckland’s own 2022 Draft Parking Strategy shows that a progressive, evidence-based path forward is not only possible but is already being pursued. The evidence is clear: prioritizing place over parking unlocks enormous potential for economic growth, community connection, and environmental sustainability.

For urban developers and policymakers ready to embrace this transformation, the following actionable recommendations provide a strategic roadmap.

- Conduct a Parking Supply Audit: Before implementing new policy, challenge the common misperception of scarcity. Map all surface lots and garages using satellite imagery and document their actual usage during normal conditions. This will establish an evidence-based baseline, reveal under-utilized supply, and counter anecdotal claims of a parking shortage.

- Prioritize the Abolition of Parking Minimums: Advocate for and implement planning reform that removes mandated parking minimums. This is the most effective way to level the economic playing field, reduce development costs, and encourage more efficient land use, particularly the adaptive reuse and infill of older sites.

- Adopt a Context-Specific Management Framework: Implement a tiered management system, like Auckland’s, that tailors parking policies to the local context. Focus the most progressive changes—such as pricing, time limits, and space reallocation—in areas well-served by public transit, such as designated Tier 3 centres.

- Launch Pilot Programs for Parking Reallocation: Initiate small-scale, high-impact projects that convert on-street parking or portions of surface lots into higher-value uses like parklets, public seating, or bike corrals. These pilots serve as tangible demonstrations of the economic and community benefits, building public support for larger-scale initiatives.

- Integrate Parking Policy with Transportation Investment: Ensure parking strategy is not developed in a silo. It must be used as a demand management tool to directly support investments in public and active transport by moderating private vehicle travel and providing better first- and last-mile connections.

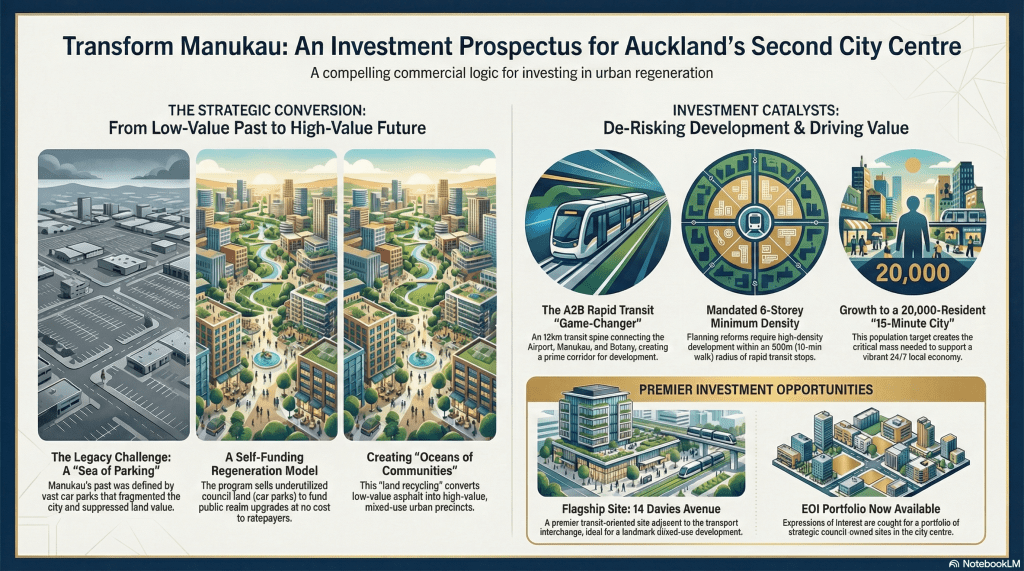

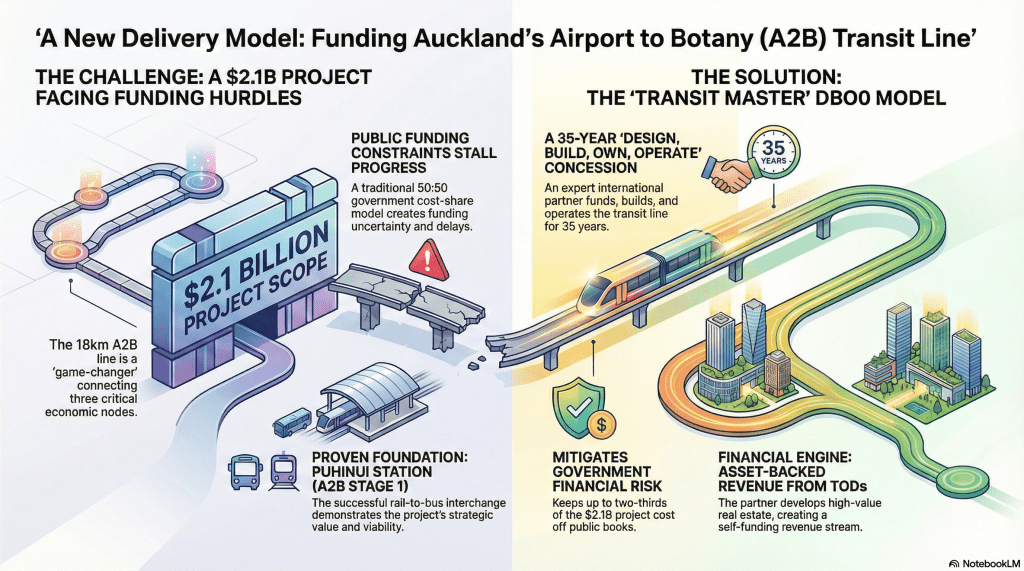

Manukau if it followed Part 9 of the Ben Does Planning Series

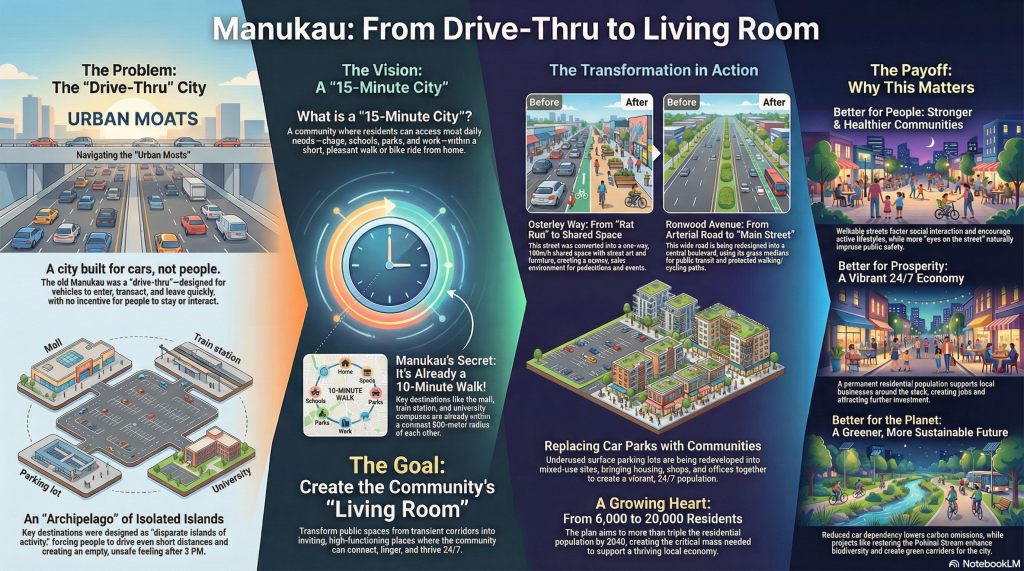

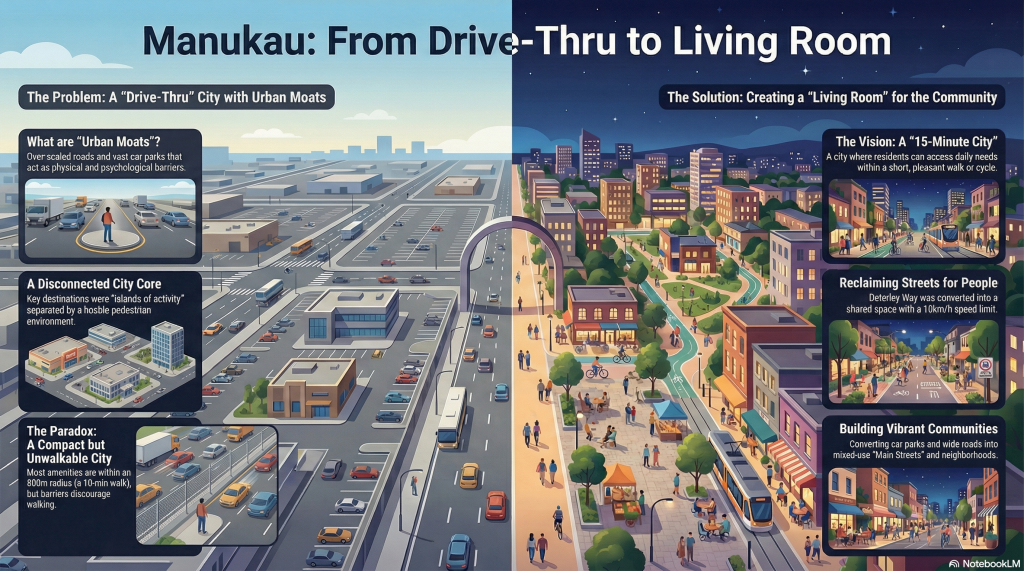

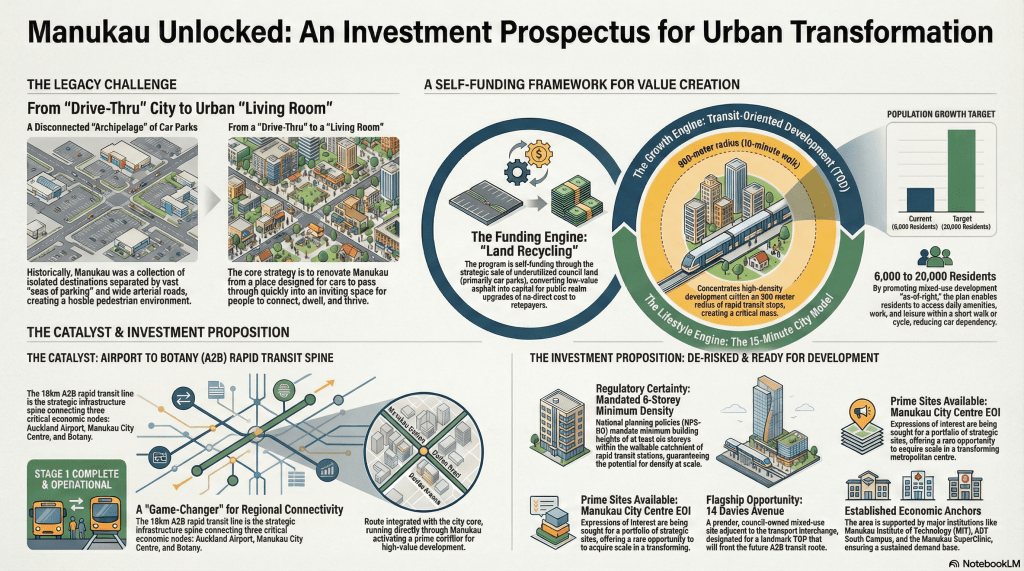

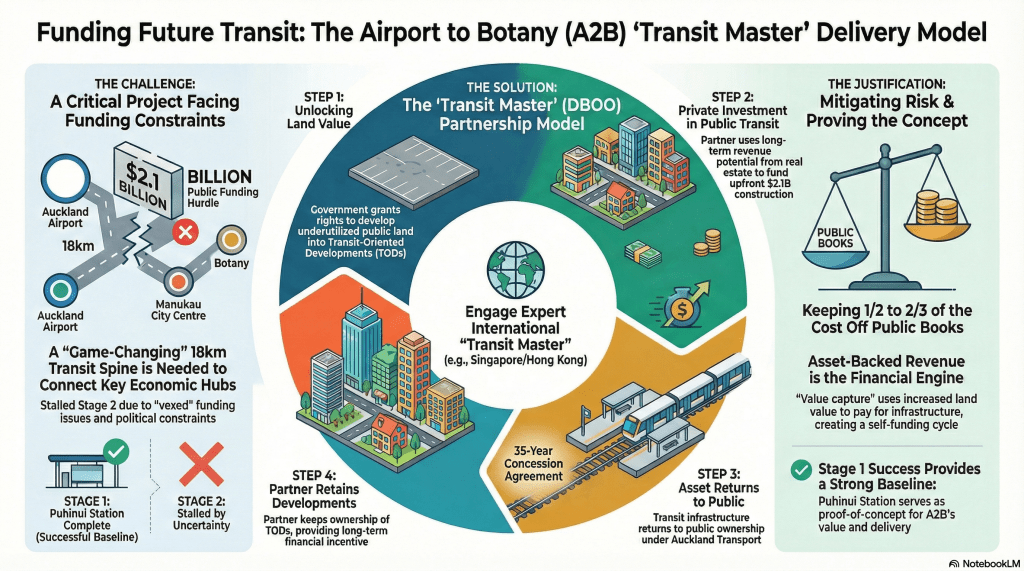

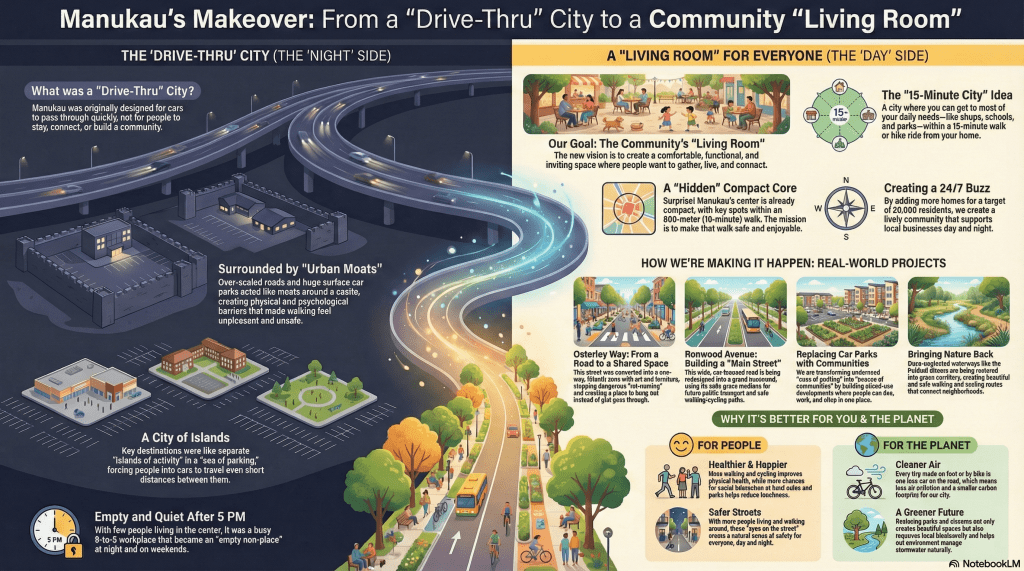

Manukau as a Living Room

Note the AI has taken some liberties with A2B station, and road name placements. The Ronwood Avenue (2 lanes) upgrade also works for the Manukau Station Road (4 lanes) upgrade. The concepts however remain the same.