Continuing from Legislative Theory to on-the-ground Design-Led Placemaking

Situation: Look out your window and be honest: you are looking at a design failure. For most of us, the street below is not a community space; it is a high-pressure water pipe designed to move the maximum volume of private steel as fast as possible. We are currently trying to run 21st-century lives on obsolete, 1950s-model hardware—a system that treats the “Daily Grind” as an inevitability rather than a glitch.

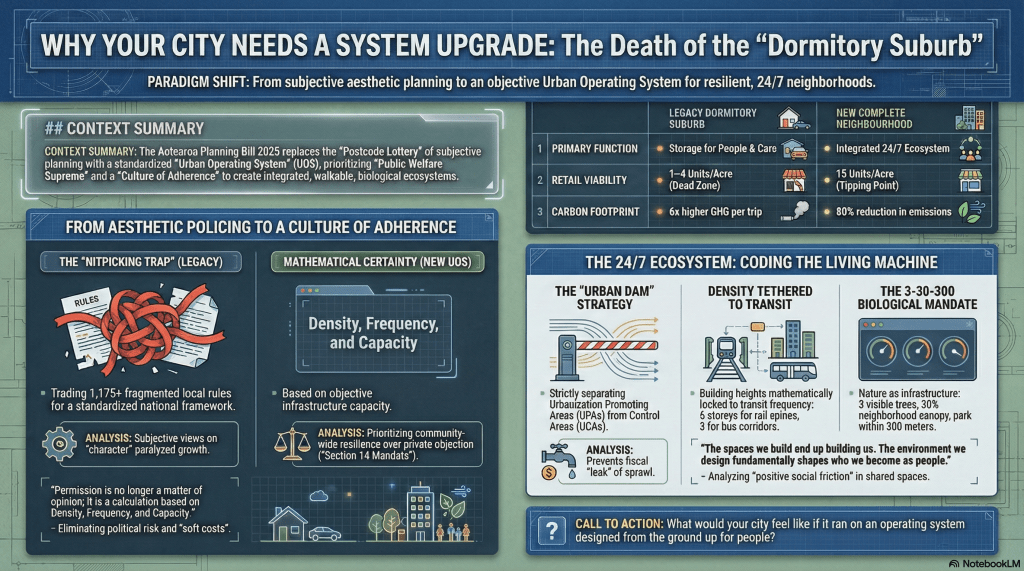

This friction was captured perfectly by a 2015 police officer who called it “unacceptable” for children to walk to school without adult supervision. Looking back from 2026, we see that comment for what it was: an admission that we had designed our habitats for traffic primacy, not for people. We have accepted “Negative Productivity”—wasted hours in gridlock—as the entry price for the modern world. But the blueprint is changing. We are moving from the “Grey Inertia” of the dormitory suburb to the “Green Resilience” of the complete neighborhood.

Here are the five radical truths of the Great Urban Upgrade.

1. Your Neighbourhood is an Operating System, Not a Sculpture

For decades, we treated city planning like a delicate sculpture, paralyzed by subjective “Character Reviews” and the aesthetic whims of neighbors. The new model replaces this “Culture of Permission” with an Urban Operating System—a clear, objective rulebook based on the “Russian Doll” concept.

In the legacy system, arbitrary height caps created “The Wedding Cake” effect: flat, monotonous blocks that turned streets into dark, oppressive tunnels. The new Urban OS utilizes the “Sculpted Skyline.”

- The Outer Box (Legal Envelope): Every site has an invisible 3D container.

- The Inner Box (Permitted Activity): If your design fits inside the math, you get “Permitted Activity” status automatically. No hearings, no objections, no “administrative debt.”

- The Chisel (The Sunlight Plane): We use diagonal line limitations—the “Chisel”—to ensure that as buildings get taller, they must retreat from the boundary. This protects the “Public Canyon” of the pavement, ensuring sunlight hits the street regardless of density.

The philosophy is simple: “Tight on Street, Loose on Building.” We strictly control the public impact (shadows and frontage) but allow autonomy of form within the envelope. We have even coded the difference between “Roads” (50km/h for movement) and “Streets” (30km/h for living).

2. The “Urban Dam” That Kills Real Estate Speculation

In the “Hydraulic City,” growth is managed like a pressurized fluid. To stop the “leaking” of unserviced sprawl, we’ve installed the Urban Dam. This is a binary system consisting of the Urbanization Promotion Area (UPA) and the Urbanization Control Area (UCA).

The UPA is the “Reservoir.” It operates on an “Infrastructure First” guarantee—pipes and transit are laid before the people arrive. On the other side of the wall sits the UCA, the legal dam where urbanization is prohibited in principle. This is the “Engine of the Soil.”

This dam does something radical: it decouples land value from housing potential. In the old system, a farm was merely a “waiting room” for a suburb, its price driven by speculative fever. With the UCA, a farm is valued for its ability to produce food. This kills speculative land banking, stabilizes the market, and protects strategic national assets like high-quality soil. As the saying goes: “The dam is what keeps them humming along.”

3. Nature is a Utility, Not a Decoration

We are finally moving past the idea of trees as “nice-to-have” aesthetic trimmings. In the resilient city, nature is reclassified as “Green Utility”—essential infrastructure on the same level as water or electricity. This biological mandate is enforced through the 3-30-300 Rule:

- 3 Trees: Every window must have a view of at least three mature trees. This is a public health mandate, not a garden tip.

- 30% Canopy: Every neighborhood must maintain 30% canopy cover to kill the “Urban Heat Island” effect and cool our streets.

- 300 Meters: Every doorstep must be within 300 meters of a high-quality public park.

Under the pavement, we’ve built the “Basement Apartment for Trees.” These are Connected Soil Volumes—Sponge City logic that treats structural soil as a tool to manage stormwater. We aren’t just planting trees; we are engineering a living urban metabolism.

4. The “Newcomer Principle”: Protecting the Right to Operate

Urban conflict is usually a battle of litigation. The new blueprint replaces this with proactive engineering through the “Newcomer Principle.” This rule solves the headache of “Reverse Sensitivity”—where a new resident moves next to an existing orchard or transit line and immediately files noise complaints.

The rule is fair: the “Agent of Change” pays for the mitigation. This creates a “Hard Shell / Soft Core” typology. If a developer builds next to a rail spine, they have a legal duty to provide:

- The Hard Shell: Mandatory acoustic glazing (triple pane) and mechanical ventilation to shield residents from noise.

- The Soft Core: The internal “Green Lung” or social sanctuary protected from the external environment.

As the legal framework states: “The developer has a legal duty to mitigate… This creates a powerful shield for existing businesses.” We have flipped the script from reactive lawsuits to upfront engineering.

5. The Health Paradox: Why the New Hospital is a Failure

Here is a truth that sounds backwards: a new multi-million-dollar dialysis center in a car-dependent suburb is a sign of planning failure. It is a symptom of a city that has engineered activity out of daily life.

We have spent decades building “Retail Wastelands”—low-density sprawl of 1–4 homes per acre where every calorie must be burned in a car. Even the most casual gamers of Cities: Skylines eventually discover this universal truth: if you try to solve every problem with more highways and wider roads, your city eventually descends into gridlock and bankruptcy.

The cure is the “Complete Neighbourhood.” To support local shops, cafes, and “Third Places” without massive parking lots, we need to hit the 15 Dwelling Units Per Acre (DU/AC) tipping point. This is the “Goldilocks Zone” of gentle density—cottage courts and fourplexes that create “Positive Social Friction.” When we build at this scale, the street becomes a “habitat,” not just a commute. As one child put it: “I like walking to school because it is our habitat.”

Conclusion: The Spaces We Build, Build Us

The transition from “Grey Inertia” to “Green Resilience” requires The Great Trade-Off. We are asking ourselves to exchange the “Quarter Acre Dream” and the freedom of chaotic, bespoke planning for the certainty and discipline of the Urban Dam.

The environment we design fundamentally shapes our health, our happiness, and our identity. We are finally building cities that work for us, rather than the other way around. If our cities are software, we must ask ourselves: “What are the most important features that we need to code into version 2.0?”